On November 20, 1959, Wendell Garrett wrote a series of letters as he frantically sought information on a portrait – painted before the American Revolution by one of the foremost artists of the colonial era – that may have once graced the walls of Adams House.. Garrett, who had embarked on graduate study in history at Harvard and was at that time working at the Massachusetts Historical Society, had been commissioned by Reuben Brower, master of Adams House, to write a history of Apthorp House on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of its construction. Then, as now, Apthorp House was the master’s lodgings at Adams House. The house had been built in 1760 by the Reverend East Apthorp, the first rector of Christ Church, Cambridge. It was a leading example of colonial architecture and had a long and distinguished history, even if its builder and first resident had left Cambridge and returned to England in 1764 as a religious controversy swirled around him. (See “Tales of an Old House,” Gold Coaster, Vol. 1, No. 2, Spring 2011) Reuben Brower took a keen interest in Garrett’s book and other efforts to commemorate Apthorp House’s bicentennial.

Garrett very much hoped to be able to include an image of the Reverend East Apthorp in his book, which was published as Apthorp House, 1760–1960 (Cambridge, Mass.: Adams House, 1960). Having heard that John Singleton Copley had painted a portrait of East Apthorp, Garrett tried repeatedly to find the portrait so that he could include a photograph of it in his book. He wrote letters to experts on colonial American art, friends, art museums, and relatives of people who may have owned the portrait. His fruitless efforts—and those of others—are chronicled in the letters and other notes that remain on file in the Adams House office. The following account is based on that archive.

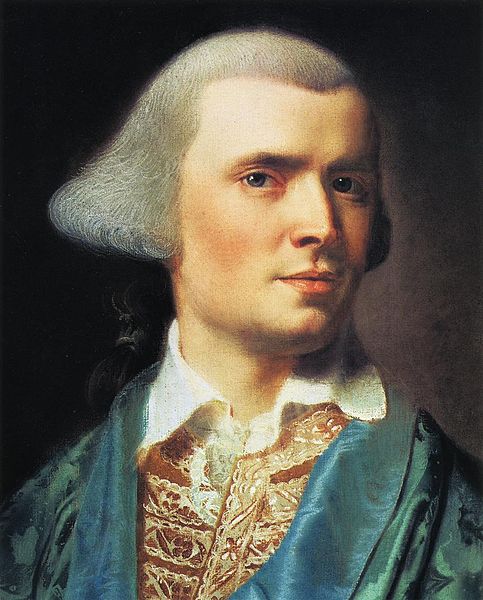

A 1769 self-portrait of John Singleton Copley, now in the Winterthur Museum

Sketchy Reports of a Portrait

John Singleton Copley (1738–1815), the purported painter of the Apthorp portrait, was one of colonial America’s most famous painters. Boston’s Copley Square is named in his honor and features a statue of him. His most important works include portraits of Paul Revere and John Hancock, as well as the eye-catching Watson and the Shark, which depicts the rescue of the unfortunate and partially dismembered Mr. Watson from a large shark in Havana harbor. Copley often painted prominent Bostonians of the pre-revolutionary era—including friends and relatives of East Apthorp—so it would not be surprising if Apthorp had sat for a portrait by Copley in the 1760s.

Although he is associated with the Americans who fought for independence in the American Revolution, Copley was averse to political agitation and many members of his family had Loyalist sympathies. He sailed from Boston to England in 1774 and, like East Apthorp, never returned to North America. The two men probably saw one another in England, where they lived until their deaths in 1815 and 1816. Apthorp became vicar of Croydon, the destination of several Loyalist families, and Copley is buried in the church of St. John the Baptist in Croydon, near Apthorp’s first wife, who died in 1782.

Two early books on Copley’s life and paintings list a portrait of East Apthorp among Copley’s works. In his 1873 volume, A Sketch of the Life and List of Some of the Works of John Singleton Copley, Augustus Thorndike Perkins referred to a Copley painting of “Rev. East Apthorp, rector of the Episcopal Church in Cambridge.” Perkins noted that the “picture is in the possession of a Miss Dexter, of Philadelphia, Penn.” The same information, with a short biography of East Apthorp, appears in Frank William Bayley’s 1915 update of the Perkins volume, The Life and Works of John Singleton Copley: Founded on the Work of Augustus Thorndike Perkins. Bayley, however, wrote that the “picture was in the possession of a Miss Dexter, of Philadelphia, Penna.” (emphasis added), suggesting that he was not sure of its location. It is unclear whether Bayley or Perkins ever tried to contact the Dexter family to confirm the existence of the portrait.

An Attempt to Contact the Dexter Family (1937)

The only known image of East Apthorp

In the late 1930s, Barbara Neville Parker and Anne Bolling Wheeler researched and wrote John Singleton Copley: American Portraits in Oil, Pastel, and Miniature (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1938). Their book also reported the existence of the East Apthorp portrait. In the course of their research, Parker wrote to a C. Joseph Dexter of Philadelphia on July 9, 1937, and enclosed a questionnaire regarding the painting. For some reason, Parker and Wheeler believed that C. Joseph Dexter’s father, the brother of a Miss Stella Dexter, might have the portrait. C. Joseph Dexter replied on July 12, 1937, and said that his father was in Vermont for the summer and would look for the portrait when he returned to Philadelphia. Mr. Dexter also mentioned that his father had some items that belonged to his sister. Barbara Neville Parker’s secretary, Lucy Thomas, apparently replied to thank Mr. Dexter and to say that they hoped the portrait could be found before the catalogue went to press in October. They did not hear anything further and did not inquire again. Years later, in October 1959, Adams House Master Reuben Brower took an interest in the purported portrait as he prepared for the bicentenary of Apthorp House. Barbara Neville Parker then wrote to Brower to explain the earlier correspondence with Mr. Dexter and speculated that “the portrait got destroyed in a fire” but gave no basis for this suspicion.

Wendell Garrett’s Efforts to Locate the Portrait (1959–1960)

In 1959, Wendell Garrett resumed the search for the Copley portrait after Brower had asked him to write a history of Apthorp House. One of the letters he wrote on November 20, 1959 went to C. Joseph Dexter of Philadelphia. Garrett wrote Dexter that “it is possible that you might have inherited from your aunt [Stella Dexter] a portrait by John Singleton Copley of East Apthorp” and explained that he was “anxious to locate the painting.” The Patterson Oil Company, where Mr. Dexter apparently had worked, promptly replied on November 23 to say that Mr. Dexter had died on July 14, 1944, and gave the address of his widow, Mrs. Ernestine C. Dexter, in Haverford, a Philadelphia suburb.

Garrett wrote to Ernestine Dexter on November 30, 1959, explaining that he had been “desperately searching” for the portrait of East Apthorp “without avail.” She replied almost immediately that she knew “nothing whatever of such a portrait” and suggested that Garrett contact Joseph Dexter’s sister, Mrs. Paul A. Chase (formerly Doris Dexter) of South Newfane, Vermont. Doris Dexter, she explained, “kept everything pertaining to the Dexters and perhaps she could at least shed some light on the subject.” From that point on, the search for the rumored Copley portrait of East Apthorp proceeded through a prolonged and complicated exchange of letters between Doris Dexter Chase, Wendell Garrett, and Reuben Brower.

On December 7, 1959, Garrett wrote to Doris Dexter Chase and reiterated his plea for help in finding the portrait. He explained that he “desperately would like a photograph” of East Apthorp and that he had “searched high and low in this country and in England.” He assured Mrs. Chase that “we do not intend to invade your privacy” in having the portrait photographed.

Doris Dexter Chase apparently replied in December 1959, although her letter is not in the Adams House files. According to an undated summary, she had a “dim memory” of an etching, engraving, or photograph of a painting that might be of East Apthorp. She wrote from her winter residence in La Jolla, California, however, and would not be able to search the attic of her Vermont house until she returned in the spring. Mrs. Chase also reported that her Aunt Stella (actually her father’s aunt) had been married twice, first to a Thomas Nash and after his death to a Mr. Shields. She said she could not remember Mr. Shields’ first name because Aunt Stella had died before she was born. According to Doris Dexter Chase, Shields had been eager to acquire Aunt Stella’s property and was said to have burned her will so that he would inherit everything. He lived in Vineland, New Jersey, but Mrs. Chase’s family never had anything to do with him. Mrs. Chase thought a nephew was his heir. Why Doris Dexter Chase found it necessary to relate this tangled family saga and whether it has any connection to the purported portrait remains a mystery. One can only speculate that the portrait may have been part of Stella Dexter’s estate.

In later years author Wendell Garrett was a frequent contributor to the Antiques Roadshow on PBS

Garrett replied on December 27, 1959, with a cautiously optimistic letter that said that he was “very encouraged to hear that you might have an etching or photograph of the painting.” He promised to “reserve a possible spot” in the book for any picture of the Apthorp portrait that Mrs. Chase might find, even though the book was to be typeset in the near future. Mrs. Chase replied immediately to say that she had thought of “another possible lead for the portrait of East Apthorp” and introduced another (apparent) relative who may have been connected to the painting. She said that “there used to be a Sydney Dexter who lived in Chestnut Hill who might be able to give you some information about the portrait.” How, if at all, this Mr. Sydney (possibly Sidney, because a Sidney Dexter was a prominent resident of Chestnut Hill) Dexter was related to Joseph and Stella and the other Dexters was not revealed. Doris Dexter Chase explained that Chestnut Hill was a suburb of Philadelphia and that she had not been there for many years. She again promised to search in her attic in Vermont in the spring, but she declared to Garrett that she was “not [at] all sure that I will be able to find anything that would be of use to you.”

Doris Dexter Chase apparently wrote to Wendell Garrett again in January 1960, but only the envelope is in the Adams House file. Garrett replied, but no copy of his letter is in the file. Mrs. Chase wrote to Garrett on May 30, 1960, and said that she was “not sure just when I’ll be able to look for East Apthorp in our attic” because her husband was seriously ill in the Hanover, New Hampshire, hospital and her hands were full. She asked what the deadline was for getting a picture to Garrett, but at that point it already may have been too late. There is no reply from Garrett in the file.

Garrett made other efforts to track down the Apthorp portrait. He made inquiries at the National Portrait Gallery, London. He wrote to Charles Coleman Sellers, librarian of Dickinson College and editor of American Colonial Painting, who replied that he would inquire in Philadelphia. He also wrote to a woman named Jessica to ask her help and mentioned that he had “already tried the Phila. Museum, Parker, Prown, and Sellers.” All these efforts yielded nothing. Garrett’s Apthorp House, 1760–1960 was published in 1960 without an image of the Copley portrait of East Apthorp, although he was able to include a silhouette of Apthorp that had been sent from England in 1807 at the request of the Reverend’s sister.

The Search Continues in 1967

After Wendell Garrett’s book was published and Adams House (and Harvard) finished celebrating the 200th anniversary of Apthorp House, Garrett apparently abandoned his quest for the portrait of East Apthorp. There are no further letters from him in the Apthorp House file at Adams House. He continued to work at the Massachusetts Historical Society, where he edited the Adams papers, and subsequently served as editor of The Magazine Antiques, wrote several books on American decorative arts, and often appeared on the public television program, “Antiques Roadshow.”

Copley wasn’t only a portraitist: perhaps his most famous large-scale work, Watson and the Shark, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Search Continues

Reuben Brower appears to have remained interested in finding the portrait long after Garrett’s book had been completed. The Adams House files suggest that the quest for the elusive painting continued until at least 1967.

In July 1967, Robert E. Apthorp (presumably a relative of East Apthorp) of Marblehead, Massachusetts, wrote to Reuben Brower with an account of his own search for the Copley portrait of East Apthorp. Robert Apthorp said that Samuel Morison had told him that the research department of the Frick Museum in New York had been very helpful in looking up an old picture. Mr. Apthorp had written to the Frick Museum, but he reported that “they find no record of such a Copley portrait” and that he was “wondering what [the] foundation was for the story.” He also said that he would write to a Professor Prown at Yale—presumably the same Prown contacted by Garrett in 1959.

A month later, in August 1967, Doris Dexter Chase wrote to Mrs. Reuben Brower to say that she had found the time to search for the portrait or an engraving of it in her Vermont farm, although she did not explain when she had conducted this search or why she was relaying this information at that time, seven years after she had proposed to make a search. Mrs. Chase had not, unfortunately, found any pictures of East Apthorp when she cleaned out her attic in Vermont before selling the farm after her husband’s death. She did, however, find “an engraving of Governor Bradford, an ancestor, who looked anything but genial.” She also said that she would find Sydney [Sidney?] Dexter’s address the next time she went to Philadelphia.

After the letters were written in 1967, the trail of the purported Copley portrait of East Apthorp went cold. There is no further correspondence in the Adams House file and no record of any attempt to contact Sydney (probably Sidney) Dexter of Chestnut Hill.

Was there ever a Copley portrait of East Apthorp? Did it once proudly hang on the walls of Apthorp House? Was it destroyed in a fire, as Barbara Neville Parker suspected? Why did Doris Dexter Chase tell Wendell Garrett and Reuben Brower about Stella Dexter’s husbands and Sydney (or Sidney) Dexter? Did those members of the Dexter family ever have the portrait? Decades have passed since Wendell Garrett’s case went cold, so it is unlikely that these questions will ever be answered. Then again, given a probable six-figure value for Adams’ missing Copley, you never know what might still turn up in an old, dusty attic.