For those of you interested in learning more about what music was like in the early years of the past century, this fascinating excerpt from the 1910 Encyclopedia of American Music details the state of affairs quite thoroughly. To make the article more enjoyable, I’ve edited the text, added the illustrations, as well as provided Wikipedia links where possible to clarify period references. (The complete original text may be found at parlorsongs.com, and a hearty thank you to them for finding and publicizing this lost work.)

The Rise of Vocal Music

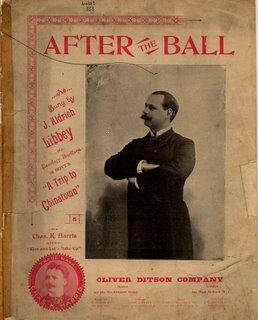

Among the popular song writers of recent years the name of Chas. K. Harris of Milwaukee has become best known, owing perhaps first of all, to the fact that he has more surely gauged the public taste than has any contemporary writer in the same field, and also because he is his own publisher. Mr. Harris was born in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1865. He early began his career as a popular song writer, composing songs to order for professional people. After the Ball (1891) was the song which first brought him into prominence. Indeed it may be said that it was this song which really, started the popular song craze as we know it today. Over $100,000 was realized by the composer from the sale of this one song alone. As will be remembered, After the Ball is a song of the ballad character and tells’ a complete story. It was first presented to the public by May Irwin in New York City, afterward being introduced in Hoyt’s A Trip to Chinatown.

Mr. Harris has stated that he received many suggestions from the stage for the subjects of popular songs. He writes: “For example, about twelve years ago such plays as The Second Mrs. Tanqueray and The Crust of Society were in vogue. I then wrote Cast Aside, Fallen by the Wayside and There’Il Come a Time Someday. Over 300,000 copies were sold of each. Then came the era of society dramas such as Belasco’s Charity Ball and The Wife. I wrote and published While the Dance Goes On, Hearts, You’ll Never Know and Can Hearts So Soon Forget; which had enormous sales.” Military dramas such as Held by the Enemy and Secret Service called out such songs as Just Break the News to Mother and Tell Her that I Loved Her, Too.

Among the many successful popular song-writers of today are William B. Gray, who made a small fortune by his Volunteer Organist; H. W. Petrie, whose name is associated with the child song I Don’t Want to Play in Your Yard; Charles Graham, who wrote Two Little Girls in Blue” Other familiar names are those of Raymon Moore, Paul Dresser, Felix McGlennon, Mabel McKinley, Edward B. Marks, Gus Edwards, Egbert Van Alstyne, Harry Von Tilzer and Nell Moret. Modern popular songs have been classified as follows: Coon Songs (rough, comic, refined, love or serenade); Comic Songs (topical, character or dialect); March Songs (patriotic, war, girl or character); Waltz Songs; Home or Mother Songs; Descriptive or Story Ballads; Child Songs; Love Ballads; Ballads of a Higher Class; Sacred Songs; Production Songs (for interpolation in big musical productions, entailing use of chorus, costumes, and stage business).

In the popular song of today the chorus is of most importance, for upon this part of the song usually rests its ultimate success or failure. The words of the chorus usually are applicable to every verse. In the descriptive song, the writer aims to tell a complete story in as few words and as graphically as possible. The success of the comic or topical song rests on the “gag” introduced into each verse and made apparent by the first or last line of the chorus. In the several classes or divisions of popular songs those of more serious character strive to make their appeal equally through both words and music; in the march song the music is of most account, while the comic song depends largely on the words.

Many reasons may be given for the ever-increasing vogue of popular music. Not the least of these is to be found in the presence of a piano or some musical instrument in nearly every home. Such was not the case a quarter century ago. The advent of the pianola and other mechanical players, together with the phonograph and gramophone also have tended to create a demand for popular music. Again, the teaching of the rudiments of music in the public schools has served to bring the art more closely before the public, with the result that nearly every girl in the country, whose parents can afford it, is receiving music lessons as a part of her general education. In homes where very little music of any kind previously had been heard it is but natural that music of a popular style at first would be most acceptable, this serving to satisfy until the taste be elevated so as to desire something of a better nature.

The appearance of singers of the first rank in musical comedy and in vaudeville undoubtedly has become a factor in forwarding the cause of popular music. While the presence of such singers in the vaudeville ranks has been deplored, the fact that they have made their appearance there has to some extent raised the standard of popular music in this country; for the class of music which they have sung has been in advance of that generally produced. There is no question but what the purveyors of popular music have shown more enterprise in the production of music that will please their patrons than have those who cater to a class with higher artistic perceptions.

Of the quantities of popular songs published in the last thirty years (ed. 1880 – 1910) but few have attained any lasting popularity. Songs of which hundreds of thousands of copies have been sold now are completely forgotten. The reason for this is hard to ascertain. It is not because the later songs are of inferior merit, for a steady advance has been made in all popular music. The public now readily accepts harmonies which but a few years ago would have been looked upon as too difficult and complicated.

In the matter of the text of our present day popular songs, however, the same advancement has not been made. There rarely is shown the same simplicity and wholesome sentiment seen in our earlier songs, such as Home, Sweet Home and Old Black Joe. Popular taste now looks for words touching on the events of the moment rather than those dealing with emotions and feeling which are common to all and which always are in evidence.

In the matter of the text of our present day popular songs, however, the same advancement has not been made. There rarely is shown the same simplicity and wholesome sentiment seen in our earlier songs, such as Home, Sweet Home and Old Black Joe. Popular taste now looks for words touching on the events of the moment rather than those dealing with emotions and feeling which are common to all and which always are in evidence.

For short periods the majority of compositions written in popular style will be very similar. Take, for instance, the introduction of ragtime melodies. At first the words of such songs dealt almost exclusively with negro characterizations. Later came songs in a quasi-Indian manner. Mexico, Japan, China were all used as ragtime suggestions. Ragtime has been much abused and its incessant use decried by many people, yet it has done much in educating the public to an appreciation of the more complicated rhythms used in music of a higher grade. The tendencies all are favorable for the production of popular music of an even better character. What would have been listened to with delight by the public a generation ago now would be looked upon as decidedly flat and uninteresting. In the light operas and musical comedies of such composers as Victor Herbert and Reginald De Koven many numbers will be found which are of real musical worth. And yet they rarely last beyond two or three years at the most. As before suggested, the inanition of the text probably is responsible for the short life of the songs, while the nervous desire of the public for something new gives to the best of the popular instrumental music of today but an ephemeral existence. Doubtless as time goes on we shall revert to the ever passing stream of popular songs and the best will be saved, until finally they become incorporated into our folk-song literature. It is only in rare cases that a tune has any lengthy existence when separated from words of universal context…

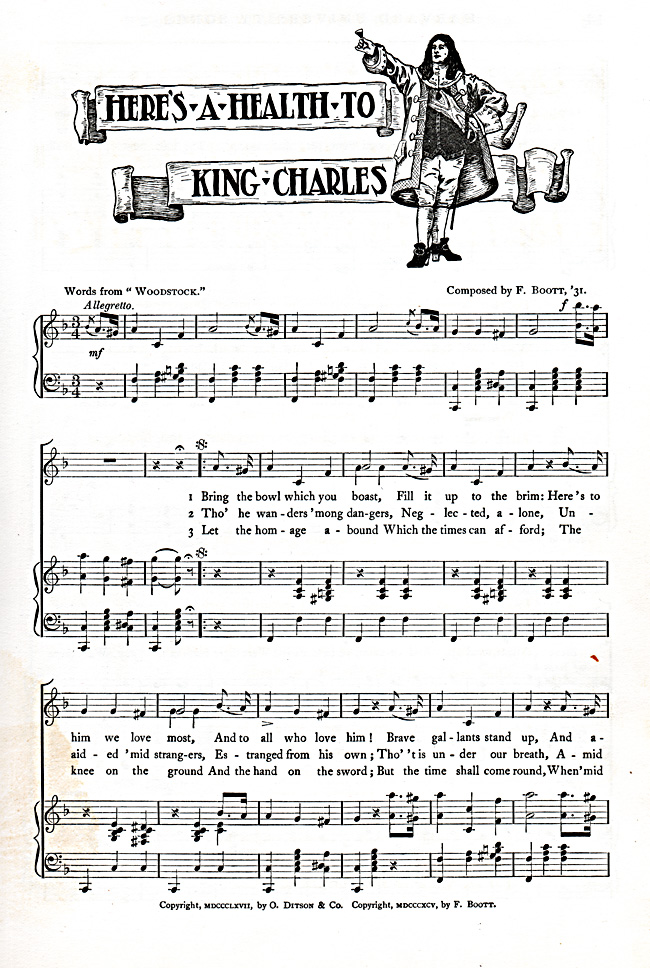

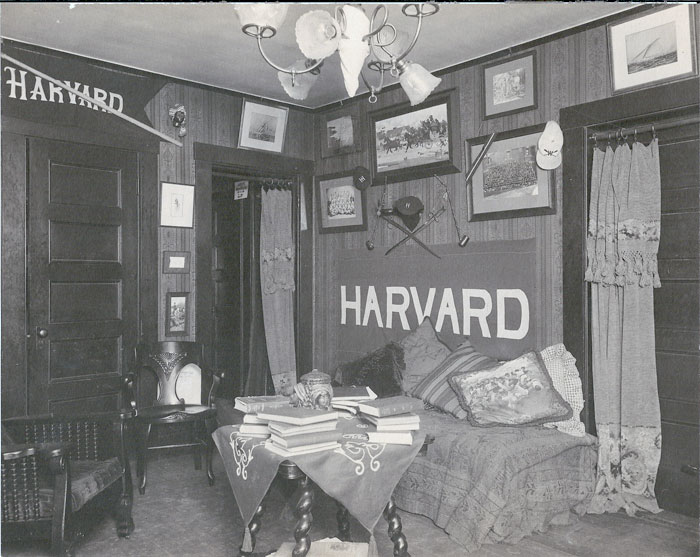

Two special classes of songs, which, in a way, may be termed popular, are college songs and gospel hymns. Of the two, the hymns more properly may be classified as popular music, insomuch as they are sung by all sorts and conditions of people, while the college songs are somewhat limited in their employment, although some of them have come into general use. Many of the latter did not originate as student songs but have been appropriated from various sources until now they are conceded to be the especial property of the undergraduate.

An early photo of the Harvard Glee Club, to which FDR belonged

The college glee club, for which many of these songs originally were indited, is patterned after the German Männerchor, though the singing and the selections hardly attain to the dignity of those of the Teutonic choruses. Nevertheless excellent musical and dramatic effects, though often of an exaggerated order, are obtained by the college men. The songs themselves, with which most of us are familiar, contain as their most salient feature a sharply marked rhythm, thus making them especially effective when given in chorus. The melodies and harmonies are pleasing and catchy, while the words usually are sentimental or humorous, certain of them being elaborations of Mother Goose rhymes. All of the larger and older institutions have their own individual songs which are looked upon as the special property of the student body, both graduate and undergraduate.

Among the songs most popular with all the colleges are Gaudeamus, Integer Vitae, Vive l’Amour, Bingo, Mary had a little Lamb, Tarpaulin Jacket, The Dutch Company, Spanish Cavalier, Good-night, Ladies, Soldier’s Farewell, Nelly was a Lady, Old Cabin Home and scores of others. It will be seen that many of these have been appropriated from the repertory of popular music in general, until they have become recognized by the public as essentially “college” songs. A special feature of student life which has given rise to many songs has been the amateur theatricals conducted by the various societies and fraternities; for in many of these productions, which often are written by the students themselves, and given elaborate presentations…

The Instrumental Song in America

Popular instrumental music in America dates practically from the period following the Civil War. True, the dance tunes of England, Ireland and Scotland previously had been used to display the musical attainments of the maiden of the period, but it was not until recent years that any effort was made to satisfy the growing demand for instrumental music of a popular style. As piano playing became more general (for the piano is the true “home” instrument, following the cabinet organ, which was not adapted to music of a showy character) several writers came forward with compositions gauged to appeal to the average musical intelligence. This music usually is formed of a simple and pleasing melody set to elemental harmony and brightened with arpeggios and similar stock passages, the whole capable of being performed, or executed, by players of small attainment. The variation pieces by A. P. Wyman, T. P. Ryder, and Chas. L. Blake, together with the operatic arrangements of James Bellak and ethers, are representative of this class of music. Well-known melodies such as Old Oaken Bucket, Nearer My God to Thee, Old Black Joe, Suwanee River, Sweet Bye and Bye and others of like character were arranged with variations. There were again other pieces, of which Silvery Waves and Maiden’s Prayer are typical of the class, which had an immense sale and which went to form the repertory of many an amateur pianist. At a later date came the various waltzes and marches and still later the two-step and pieces of the intermezzo character.

Popular instrumental music in America dates practically from the period following the Civil War. True, the dance tunes of England, Ireland and Scotland previously had been used to display the musical attainments of the maiden of the period, but it was not until recent years that any effort was made to satisfy the growing demand for instrumental music of a popular style. As piano playing became more general (for the piano is the true “home” instrument, following the cabinet organ, which was not adapted to music of a showy character) several writers came forward with compositions gauged to appeal to the average musical intelligence. This music usually is formed of a simple and pleasing melody set to elemental harmony and brightened with arpeggios and similar stock passages, the whole capable of being performed, or executed, by players of small attainment. The variation pieces by A. P. Wyman, T. P. Ryder, and Chas. L. Blake, together with the operatic arrangements of James Bellak and ethers, are representative of this class of music. Well-known melodies such as Old Oaken Bucket, Nearer My God to Thee, Old Black Joe, Suwanee River, Sweet Bye and Bye and others of like character were arranged with variations. There were again other pieces, of which Silvery Waves and Maiden’s Prayer are typical of the class, which had an immense sale and which went to form the repertory of many an amateur pianist. At a later date came the various waltzes and marches and still later the two-step and pieces of the intermezzo character.

Sousa

Foremost among the successful American writers of popular instrumental music stands the name of John Philip Sousa, the “March King.” It has been said that Sousa writes with the metronome at his elbow running at one hundred and twenty clicks to the minute. Sousa’s marches never have been surpassed and rarely equaled. They are without doubt the most typical music which this country has yet produced, for they are indeed deeply imbued with the American spirit.’ Sousa above all others has caught the true martial swing; his music also has the stamp of his own distinct individuality and he practically has revolutionized march music. No other composer, not even Johann Strauss, has attained such world-wide popularity as has Sousa. His music has been sold to thousands of bands in the United States alone and has been heard in all parts of the civilized world. It has been very aptly stated that Sousa’s marches contain all the nuances of military psychology, the long unisonal stride, the grip on the musket, the pride in the regiment and the esprit de corps. They also have served as dance music, and the two-step was directly borne into vogue by them.

John Philip Sousa was born in Washington, D. C., on Nov. 6, 1859, his mother being a German and his father a Spanish political exile. At eight years of age Sousa was playing the fiddle in a dancing school and at sixteen led anorchestra in a variety theatre. Two years later he became director of a traveling theatrical troupe, composing music for the members and also appearing in negro minstrel roles. At nineteen he toured the country as a member of Often-bach’s Orchestra, and shortly after he became director of the Pinafore Opera Company. For some years after this he directed the United States Marine Band and in 1892 formed his own Concert Band. His career from this time on is familiar to the American public. Sousa’s chief claim to fame lies in his marches, from which he has derived a princely income. The most popular of these are Washington Post, Liberty Bell, High School Cadets, King Cotton, Manhattan Beach, El Capitan and Stars and Stripes Forever. As will be seen, the titles are derived either from patriotic subjects or from some subject-matter of national import or interest. Sousa’s efforts in the comic opera field receive mention elsewhere in this chapter.

Marked advancement in the public taste for instrumental music has been shown in recent years and many compositions of an artistic nature have been adopted into the repertory of popular music. Pieces such as Handel’s Largo, Rubinstein’s Melody in F, Nevin’s Narcissus and even Schumann’s Traiumerei may now be classed as popular music. The concert bands have done much in familiarizing the public with music of this character, and it is no uncommon thing to find the public making special requests for the works of Wagner and Liszt. Another feature which has tended to elevate the popular taste for instrumental rather than for vocal music is the general study of the piano by the young. The teaching material of necessity is of higher grade than the songs commonly sung and America has gained much from the general introduction of the piano into the home.

Light Opera and Musical Comedy

In light opera and musical comedy is seen the most elaborate phase which popular music has assumed. Of late years the country has been deluged with musical plays until their effect has been felt on the legitimate drama. These productions are the natural sequence of the decadent minstrelshow, and while they lack the dignity, if such a word may here be used, of the comic operas of the European peoples, the American public has wafted them into favor until they have become the most popular form of entertainment presented on the stage.

The better class of American light operas is built somewhat after the style of those of Gilbert and Sullivan, while the “near” operas or musical comedies are simply a series of solos, concerted pieces and choruses held together by a mere thread of a plot. Several of the better sort have become standards and bid fair to remain for some years to come; but the vogue of the vast majority is fleeting, lasting at the best but for a few years.

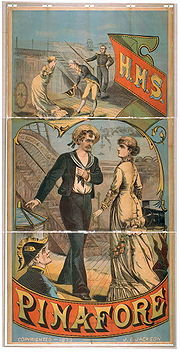

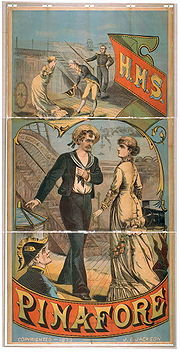

Light opera first sprang into favor with the American public in 1878, in which year James C. Duff, a brother-in-law of Augustin Daly, brought from England Gilbert and Sullivan’s H. M. S. Pinafore and produced it at the Standard Theatre (now the Manhattan) in New York. The success of the charming opera was remarkable, and as there was no copyright on the work different managers at once took it up and within a short time five theatres in New York alone were playing it to full houses. Such was the furore which “Pinafore” created that soon it was being produced in all parts of the country and by all sorts of companies–children’s, church-choir, and even negro.

Light opera first sprang into favor with the American public in 1878, in which year James C. Duff, a brother-in-law of Augustin Daly, brought from England Gilbert and Sullivan’s H. M. S. Pinafore and produced it at the Standard Theatre (now the Manhattan) in New York. The success of the charming opera was remarkable, and as there was no copyright on the work different managers at once took it up and within a short time five theatres in New York alone were playing it to full houses. Such was the furore which “Pinafore” created that soon it was being produced in all parts of the country and by all sorts of companies–children’s, church-choir, and even negro.

When the “Pinafore” craze struck Boston a Miss Ober decided to form a company composed of the best church and concert singers of the city in order to produce the popular operetta in the most adequate manner possible. She was successful in bringing together an excellent organization which took the name of the Boston Ideal Pinafore Company. The outcome of this was the famous Bostonians, which survived the “Pinafore” craze and which for so many years maintained undiminished popularity. From this company came many of the best light opera singers which this country has produced, among them being Jessie Bartlett Davis, Adelaide Phillips, Marie Stone, H. C. Barnabee, Myron W. Whitney, Eugene Cowles and Tom Karl. No other company of American singers ever has achieved such lasting success as did the Bostonians. For twelve years they toured the country, season after season, until they became a national institution. Their repertory included all the popular light operas of their day, but DeKoven’s Robin Hood became the especial favorite, this opera receiving over a thousand performances at their hands.

The name of John A. McCaull for many years was associated with the production of light opera in New York. When, in 1880, Pirates of Penzance was brought out by Gilbert and Sullivan, precautionary measures were taken to prevent American pirates from appropriating the score and an alliance with Mr. McCaull was formed to produce the new work at the Fifth Avenue Theatre. About this time Rudolph Aronson instituted the Casino, and for several seasons McCaull supplied the company in which Francis Wilson was the principal comedian. Mr. McCaull then took charge of Wallack’s Theatre, and it was in this house that he made his best productions. The stock company which he formed was of unusual excellence and included De Wolfe Hopper, Jefferson de Angelis, Digby Bell, Laura Joyce, Marion Manola and Eugene Ondine. So successful did the company become that its very success led to its downfall, for the best talent too soon followed Francis Wilson into the world of star productions, and as a result the organization suffered a decline.

The “star” system largely was responsible for the decadence of light opera of the better class, for good general ensemble was allowed to suffer in order to exploit the “star” or “stars.” Instead of the opera being written as an exposition of suitable music and libretto, such as contained in the Gilbert and Sullivan and earlier DeKoven operas, it became merely a vehicle to bring forward this or that “star” with his or her peculiar limitations, vocally or histrionically skil-fully concealed. Thus it was that light opera degenerated into musical comedy, for undoubtedly it is a degeneration, and the productions of recent years are no longer properly to be classed with light opera.

The musical comedy of today partakes of the character of the old German singspiel or song-play, in which the spoken dialogue was interspersed with musical numbers. As before stated, it is a decadent form of comic or light opera and its forte is dramatic rather than musical, for the music is brought in rather as incidental than as an integral part of the performance. Many of the popular musical comedies were first brought out by organizations or clubs connected with well-known societies and colleges prominent among which are the “Cadets of Boston,” the “Hasty Pudding Club” at Harvard, “Monk and Wig” at University of Pennsylvania, and “The Strollers” at Columbia. The Boston “Cadets” particularly have placed many hits to their credit, 1492 and Jack and the Beanstock being especially successful.

DeKoven

Among all the American light operas those of DeKoven and Herbert are intrinsically the best, for they are cleverly put together and show the evidence of musicianly treatment. America. however, has never produced a writer of librettos to at all compare with W. S. Gilbert of Gilbert and Sullivan fame, and without the requisite of a good libretto no opera, no matter what its musical value, can attain to lasting popularity. The operas of Reginald DeKoven, of which he has written fifteen, have achieved wide popularity. Robin Hood alone has been enacted more than three thousand times, while The Fencing Master, The Highwayman (which is considered his best work), Foxy Quiller, Red Feather, Maid Marion, The Little Duchess, Rob Roy, and others have all had successful runs. Mr. DeKoven also has written two ballets The Man in the Moon and The Man in the Moon, Jr., as well as many songs which have had a large sale. More than a million copies of Oh, Promise Me alone have been sold. DeKoven now stands at the head of our writers of popular music of the better class. He was born in Middletown, Connecticut, in 1859, and now is a resident of New York.

Victor Herbert, an American by adoption, is another writer who has made a reputation for himself in the light opera field. Although he has composed more serious works and has been associated with musical matters of a higher order he is best known by his lighter creations. Mr. Herbert is a native of Ireland and first came to this country in 1886, when he joined the Metropolitan Opera Company in New York. He for several seasons was first cellist of the Theodore Thomas Orchestra, later became the conductor of the Symphony Orchestra in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, which position he held for a number of years, and then formed an orchestra of his own in New York. His operas and musical comedies, while possibly not of quite as high an order as those of DeKoven, are extremely tuneful and pleasing and always show the touch of the musician. Among the most popular are The Wizard of the Nile, Serenade, The Idol’s Eye, The Fortune Teller, Babes in Toyland, Babette, It Happened in Nordland, The Red Mill, Mdlle. Modiste, which latter has served to perfect the establishing of Fritzi Scheft as a light opera singer.

Three American teams of light opera and musical comedy writers, Smith & DeKoven, Barnet & Stone, and Pixley & Luders, have become well known; for the joint works which they have produced have been among the best of their class. With the work of the librettists we are not especially concerned, notwithstanding the fact that on the libretto depends to a large extent the success of an opera. The music of DeKoven as well as that of Victor Herbert, who perhaps is his nearest competitor, already has been noted. R. A. Barnet’s best works undoubtedly are 1492 and Jack and the Beanstock, which latter work developed into one of the best extravaganzas ever produced on the American stage. Gustave Luders has many successes placed to his credit, such as Prince of Pilsen, King Dodo and Grand Mogul.

Cohan

Edgar Stillman Kelley wrote a comic opera Puritania,which was excellent musically, but which suffered through the libretto. Sousa has brought out several operas, El Capitan, The Charlatan, The Bride Elect and The Free Lance, as well as an extravaganza, Chris and the Wonderful Lamp, each of which had some success. The youngest and one of the most typical of musical comedy writers is Geo. M. Cohan. Mr. Cohan was born at Providence, Rhode Island, on July 4, 1878, and it is most fitting that his contributions to popular music should catch the American spirit. The “Yankee Doodle Boy,” as he has been called, very aptly describes both him and his music. Little Johnny Jones, Forty-five Minutes from Broadway, George Washington, Jr. and Fifty Miles from Boston have won fame and fortune for him while he is still under thirty.

It is almost impossible to judge of the composer of our current musical comedies, for so many songs by writers other than the originator are interpolated that the name of the initiatory writer becomes lost in the hodge-podge finally produced. The musical comedies of today recall the “Ballad Operas” of more than a century ago, and it is seen that we thus have reverted to the tastes of our forefathers. Truly, there is nothing new under the sun. The only difference to be seen is in the character and make-up of the music itself, for the structure of musical comedy is very similar to that of the Beggar’s Opera.

In the true comic or light opera the librettist aims to form either a consistent farcical story or a clever satire, but in musical comedy this unfortunately is hardly considered necessary. So long as there are two or three acts of more or less amusing dialogue, striking stage pictures and taking music, nothing more is regarded as of importance. Although not an American production Franz Lehar’s Merry Widow, which has taken the world by storm, may be cited as a typical light opera of today, while Victor Herbert’s Red Mill is characteristic of musical comedy. The difference in general make-up easily may be noted and compared.

May

The enumeration of the musical comedies, writers of such works, and singers and players appearing in the same within recent years, is out of the question, for new writers and performers are continually coming forward and the existence of the works themselves at the best is but a matter of a few years. As representative writers of musical comedy, beside those already spoken of may be cited Richard Carle, Gus Edwards, Raymond Hubbell, Joe Howard, A. B. Sloane, Jean Schwartz, Alfred Robyn and M. Klein. Numbers of adaptations of English, French and German musical comedies and’ extravaganzas” as well as our own products have been successfully exploited in this country within the last few years. From the time when Francis Wilson first was brought forward as a star there has been a steady stream of singers of the lighter musical works who have won fame for themselves in this field. Some, such as Alice Nielsen, have used the light opera roles as stepping stones to more ambitious achievements, while there are again others who have reversed the process. There are many names beside those already enumerated which have become closely associated with the more popular musical productions of the American stage. It will suffice to mention the following as representative of their class: Lillian Russell, Virginia Earle, Fay Templeton, Madge Lessing, Marie Cahill, Camille D’Arville, Marie Tempest, Edna Wallace Hopper, Lulu Glaser, Edna May, Jeff De Angelis, De Wolfe Hopper, Richard Carle and Frank Daniels. It will be seen that the laurels in its field rest with the fair sex. Williams and Walker occupy a unique place through their excellent presentation of musical plays by a company composed wholly of negroes.

What will be the next phase to be assumed by popular music in this country is impossible to state. However, it appears highly probable that within a few years there will come a revulsion of feeling against the inanities of musical comedy, and the more legitimate forms of light opera again will assume their place in public favor. Despite the outcry heard in some quarters against the popular music of the day, it is serving its purpose in educating the public to desire something better. Popular music in its various forms alwayswill have a place, for it is music which the musically uncultured can enjoy. Just as art music continually is changing its character and structure, so is popular music undergoing the same evolution, and the last word has not been said in either field. From the fact that musical culture ever is becoming more general, it is but natural to assume that the increased familiarity of the public with music of the better class must have its effect on the popular productions. An unbiased investigator will find marked improvement in the general trend of popular music produced in the last twenty-five years, and we still are advancing.

Edward Penfield

Edward Penfield

In the matter of the text of our present day popular songs, however, the same advancement has not been made. There rarely is shown the same simplicity and wholesome sentiment seen in our earlier songs, such as

In the matter of the text of our present day popular songs, however, the same advancement has not been made. There rarely is shown the same simplicity and wholesome sentiment seen in our earlier songs, such as

Popular instrumental music in America dates practically from the period following the Civil War. True, the dance tunes of England, Ireland and Scotland previously had been used to display the musical attainments of the maiden of the period, but it was not until recent years that any effort was made to satisfy the growing demand for instrumental music of a popular style. As piano playing became more general (for the piano is the true “home” instrument, following the cabinet organ, which was not adapted to music of a showy character) several writers came forward with compositions gauged to appeal to the average musical intelligence. This music usually is formed of a simple and pleasing melody set to elemental harmony and brightened with arpeggios and similar stock passages, the whole capable of being performed, or executed, by players of small attainment. The variation pieces by A. P. Wyman, T. P. Ryder, and Chas. L. Blake, together with the operatic arrangements of James Bellak and ethers, are representative of this class of music. Well-known melodies such as Old Oaken Bucket, Nearer My God to Thee, Old Black Joe, Suwanee River, Sweet Bye and Bye and others of like character were arranged with variations. There were again other pieces, of which Silvery Waves and Maiden’s Prayer are typical of the class, which had an immense sale and which went to form the repertory of many an amateur pianist. At a later date came the various waltzes and marches and still later the two-step and pieces of the intermezzo character.

Popular instrumental music in America dates practically from the period following the Civil War. True, the dance tunes of England, Ireland and Scotland previously had been used to display the musical attainments of the maiden of the period, but it was not until recent years that any effort was made to satisfy the growing demand for instrumental music of a popular style. As piano playing became more general (for the piano is the true “home” instrument, following the cabinet organ, which was not adapted to music of a showy character) several writers came forward with compositions gauged to appeal to the average musical intelligence. This music usually is formed of a simple and pleasing melody set to elemental harmony and brightened with arpeggios and similar stock passages, the whole capable of being performed, or executed, by players of small attainment. The variation pieces by A. P. Wyman, T. P. Ryder, and Chas. L. Blake, together with the operatic arrangements of James Bellak and ethers, are representative of this class of music. Well-known melodies such as Old Oaken Bucket, Nearer My God to Thee, Old Black Joe, Suwanee River, Sweet Bye and Bye and others of like character were arranged with variations. There were again other pieces, of which Silvery Waves and Maiden’s Prayer are typical of the class, which had an immense sale and which went to form the repertory of many an amateur pianist. At a later date came the various waltzes and marches and still later the two-step and pieces of the intermezzo character.

Light opera first sprang into favor with the American public in 1878, in which year James C. Duff, a brother-in-law of Augustin Daly, brought from England Gilbert and Sullivan’s

Light opera first sprang into favor with the American public in 1878, in which year James C. Duff, a brother-in-law of Augustin Daly, brought from England Gilbert and Sullivan’s