The alliance between Saudi Arabia and the United States goes back seven decades, to when King Abdulaziz, the founder of the modern Saudi state, met President Franklin Delano Roosevelt aboard the U.S.S. Quincy at the Great Bitter Lake in the Suez Canal.

New York Times, September 29, 2016

With Saudi-American relations in the news again, I thought it worth remembering that today’s alliance had its beginnings in one last bit of Rooseveltian personal diplomacy: an attempt to use his redoubtable skills on behalf of European Jews.

The meeting with King Abdulaziz (often known in the West as Ibn Saud) took place immediately following the Yalta Conference in February 1945 when the Big Three—Winston Churchill, Josef Stalin, and Roosevelt—hammered out the final diplomatic agreements of the Second World War. Besides the conference with Ibn Saud, Roosevelt also arranged meetings with King Farouk of Egypt and Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia that are little remembered today.

By scheduling the meetings without Churchill’s knowledge, Roosevelt breached the United States’ longstanding hands-off policy respecting Britain’s sphere of influence in the region. When Churchill learned of the meetings, he hastened to schedule talks of his own. But a change was already under way.

The strategic importance of the Middle East had become increasingly clear during the war, and Roosevelt’s economic and military advisers were anxious to secure America’s military presence in the Middle East—as well as cement America’s budding oil-drilling partnership with Saudi Arabia. These were solid reasons for Roosevelt to meet with Ibn Saud, but there is ample evidence that Palestine was the main purpose of the president’s visit.

In 1944 both Republicans and Democrats vied for Jewish votes with pro-Zionist planks in their campaign platforms. But this statement from Roosevelt, read to the Zionist Organization of America on October 15, confirmed the loyalty of American Jewry to the Democratic Party. “I know how long and ardently the Jewish people have worked and prayed for the establishment of Palestine as a free and Democratic Jewish commonwealth. I am convinced that the American people give their support to this aim, and if reelected, I shall help to bring about its realization” (quoted in Breitman and Lichtman, p. 259).

Historian Robert Rosen and others point out that Roosevelt had also privately promised his Jewish friends to try to solve the problem of Palestine before the war was over. Before he left for Yalta, he conferred with Rabbi Stephen Wise and told his Cabinet that he would meet Saud and “try and settle the Palestine situation” (quoted in Rosen, pp. 409–410). Historians Richard Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman recount that after the election he began to make plans for the Yalta trip, stating to Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius, “I am going to take a trip [the Yalta Conference] this winter and will see a lot of people. . . . I want to see if I can’t unravel this whole situation [the question of Palestine] on the ground,” leading them to conclude that Roosevelt hoped to use his personal, persuasive diplomacy to settle matters on Palestine (p. 297). In early January, Roosevelt told Stettinius that when he met with Ibn Saud after Yalta, he wanted a map with him that showed the small size of Palestine in relation to the Arab world in order to make the case that “he could not see why a portion of Palestine could not be given to the Jews without harming in any way the interests of the Arabs with the understanding, of course, that the Jews would not move into adjacent part of the Near East from Palestine” (Breitman and Lichtman, p. 299).

Franklin Roosevelt and Ibn Saud meeting aboard the U.S.S. Quincy, February 14, 1945.

Roosevelt’s translator at Yalta, Charles Bohlen, recorded in his memoirs Witness to History (p. 212) that Roosevelt raised the subject with Stalin during the Yalta Conference in a controversial conversation that contained an unfortunate remark that led some to label Roosevelt anti-Zionist. Breitman and Lichtman interpret the anti-Semitic exchange as an “ice-breaker,” which Roosevelt used to test the waters of Stalin’s potential opposition to a Jewish homeland in Palestine—and found no resistance (p. 301). Roosevelt biographer Frank Freidel agrees, “In actuality Roosevelt was stubbornly pro-Zionist, and had a difficult time with Ibn Saud when he tried to persuade the king to accept 10,000 more Jews in Palestine” (p. 594). Breitman and Licthman also tell us that Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, who worked closely with the president, believed that Roosevelt “like the late Justice Brandeis, thought a Jewish state would become a model of social justice and would raise standards of living in the region. FDR also knew that Saudi Arabia badly needed outside funds for development. Surely a farsighted Arab leader would recognize such benefits—along with the advantages of American aid” (p. 299) Adding to all of these considerations, the liberation of Auschwitz by the Red Army in late January revealed to the world the horrors of the Holocaust. Thomas Lippman, another scholar of the subject, states categorically that Roosevelt met with Ibn Saud because “the Jews had a claim on the world’s conscience, and on Roosevelt’s” (p. 3).

By all accounts the meeting with King Abdulaziz was extraordinary. Ibn Saud and his retinue of 47—which included an astrologer and food taster—traveled across the Arabian peninsula from Riyadh to Jeddah where they boarded the U.S.S. Murphy for a two-day sail on the Red Sea to Great Bitter Lake in the Suez Canal. Only once before had the king left the Arabian peninsula. Fitted out for the king’s use, the Murphy’s deck was covered with colorful carpets and shaded by an enormous brown canvas tent. A flock of sheep, brought along for fresh meat, grazed in a corral. Food was cooked on charcoal braziers on the deck. Abdulaziz, 64 years old, a large and imposing black-bearded man dressed in Arab robes, his headdress regally bound with golden cords, was seated on a golden throne. The king was attended by barefoot Arab warriors armed with long rifles, each with a scimitar bound to his waist. One American witness described it as “a spectacle out of the ancient past on the deck of a modern man-of-war” (quoted in Lippman, p. 2).

Roosevelt waited on the U.S.S Quincy, surrounded by his own retinue of admirals and high-ranking diplomats. Ibn Saud was transferred to the Quincy and the two leaders, meeting from 10 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. on February 14, 1945, forged an improbable alliance that linked the two nations and shaped the history of the Middle East for decades to come.

I first learned about the meeting between Roosevelt and King Abdulaziz in 2003 when American Counsel to Saudi Arabia, Hugh Geohagan, visited the Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park. His purpose was to discuss returning to the Library a collection of objects that had been borrowed a few years earlier for an exhibition, “Gifts of Friendship,” in the King Abdulaziz Archives in Riyadh. Held in 2002, the exhibition commemorated the centennial of Abdulaziz’s rule by displaying the state gifts that he and Roosevelt exchanged in their shipboard meeting in 1945.

DC-3 passenger plane given by FDR to King Abdelaziz.

Ibn Saud’s gifts to FDR included brightly colored camel’s hair robes embroidered with gold, hand-painted perfume bottles, a bottle of granular musk, lumps of ambergris, a gold dagger set with diamonds, and a gold filigree sword and belt set with diamonds. In return FDR famously gave the king a DC-3 passenger plane (fully staffed with a crew supplied by the U.S), which marked the beginning of the Saudi Air Force. When he saw that the king had trouble walking, FDR spontaneously gave him one of his wheelchairs. The gifts were extraordinary, but not as extraordinary as the meeting itself.

Formal talks began after they had exchanged the gifts and enjoyed lunch and Arabian coffee. “Roosevelt came straight to the most urgent point: the plight of the Jews and the future of Palestine, where it was already apparent that the governing mandate bestowed upon Britain by the League of Nations twenty years earlier would come to an end after the war” (Lippman, p. 8).

Memoir of the meeting by Col. William A. Eddy, U.S. Minister to Saudi Arabia and translator of the meeting.

An account of the conversation, FDR Meets Ibn Saud, was published by U.S. Minister to Saudi Arabia Col. William A. Eddy, who was deeply involved in the intricate intercultural arrangements for the meeting. Born in what is now Lebanon, Eddy was fluent in Arabic, and as translator, was the only person to hear both sides of the conversation between the two leaders. As quoted from Eddy’s account in Rosen (pp. 412–413), “President Roosevelt was in top form as a charming host, witty conversationalist, with the spark and light in his eyes and that gracious smile which always won people over to him whenever he talked with them as a friend. . . . With Ibn Saud he was at his very best.” Roosevelt said that he felt “a personal responsibility” for the Jewish victims of the Holocaust who had suffered “indescribable horrors at the hands of the Nazis: eviction, destruction of their homes, torture, and mass murder” and asked the king for his advice. The king replied that the Allies as victors should give the Jews and “their descendants the choicest lands and homes of the Germans who had oppressed them.” Roosevelt responded that the Jews had a deep desire to settle in Palestine and were fearful of remaining in Germany. The king said he did not doubt that the Jews did not trust the Germans, but “surely the Allies will destroy Nazi power forever and in their victory will be strong enough to protect Nazi victims. If the Allies do not expect firmly to control future German policy, why fight this costly war?” He lectured the president on the long history of animosity between Arabs and Jews.

Continuing with Eddy’s account as recounted in Rosen, Roosevelt persisted, saying that he counted on Arab “hospitality” and on the king’s help solving the problem of Zionism, but the king repeated his position. “Amends should be made by the criminal, not by the innocent bystander. What injury have Arabs done to the Jews of Europe? It is the ‘Christian’ Germans who stole their homes and lives.” Later Roosevelt returned a third time to the subject. The king lost patience, observing that American “oversolicitude for the Germans was incomprehensible to an uneducated Bedouin with whom friends get more solicitude than enemies.” Ibn Saud’s final remark on the subject reiterated his unalterable position. According to Arab custom, he said, survivors and victims of battle were distributed among the victors according to their number and their supplies of food and water. Palestine, he said, was a small, land-poor country “and had already been assigned more than its quota of European refugees.” Still Roosevelt persevered. “The Arabs would choose to die,” he told the president, “rather than yield their land to the Jews.” Roosevelt offered economic aid, irrigation projects, and improved living standards for the Saudi people who were then poverty stricken by war-time disruptions to their economy (quoted in Rosen, pp. 413–414).

But the king was adamant. Was his confidence shaken? He later told Eleanor Roosevelt that his failure to convince Ibn Saud was his one complete failure. To Rabbi Wise he said, “I most gloriously failed where you are concerned.” To Congress, in his report on the Yalta Conference, he said only, “I learned more about that whole problem, the Moslem problem, the Jewish problem, by talking with Ibn Saud for five minutes than I could have learned in the exchange of two or three dozen letters.” He later reported to Wise:

There was nothing I could do with him. We talked for three hours and I argued with the old fellow up hill and down dale, but he stuck to his guns. He said he could see the flood engulfing his lands, Jews pouring in from Eastern Europe and from America, from the Riviera and from California, and he could not bear the thought. He was an old man and he had swollen ankles and he wanted to live out his life in peace without leaving a memory of himself as a traitor to the Arab cause [quoted in Rosen, p. 415].

Roosevelt himself had less than two months to live. Judge Joseph Proskauer later recalled that FDR was frightened now for the Jews in Palestine. He believed that “either a war or a pogrom would ensue” (quoted in Rosen, p. 416).

Diamond and gold dagger and scabbard given by King Abdulaziz to FDR. Courtesy FDR Library and Museum.

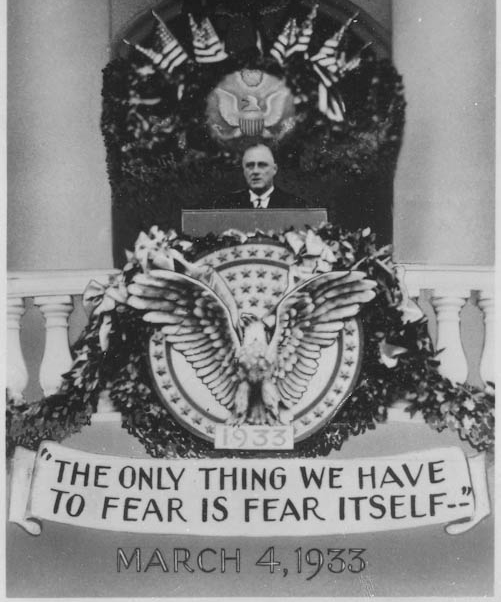

Why did he do it? This was one of Roosevelt’s last acts. Surely he knew that his life was slipping away. Too ill to endure a fourth inauguration ceremony on Capitol Hill, a swearing in was held at the White House followed by the second briefest inaugural address in history. Yet two days later he began his 14,000-mile journey to Yalta, where he secured his twin priorities of Soviet entry into the war in the Pacific and Stalin’s commitment to the United Nations. It was only Roosevelt’s vision of a secure and peaceful postwar world that sustained him—not only at Yalta, but also to extend his arduous journey and meet with King Abdulaziz.

Many historians have reported on Roosevelt’s supreme confidence, his steadfast belief that through personal diplomacy—by meeting adversaries face to face—he could solve problems that stymied others. Breitman and Lichtman report on a telling incident, “After attending a presidential session on the Middle East, State Department economic advisor Herbert Feis said, ‘I’ve read of men who thought they might be King of the Jews and other men who thought they might be King of the Arabs, but this is the first time I’ve listened to a man who dreamt of being King of both the Jews and the Arabs’” (quoted in Breitman and Lichtman, p. 299).

Despite his own failure at Great Bitter Lake, Roosevelt’s belief in the power of personal diplomacy was intact. It was, after all, the foundational idea for the United Nations—that is, that seemingly intractable problems can be solved in a world organization that brings people together to overcome their differences. A belief fervently shared by Eleanor Roosevelt, for FDR it was the only hope that the world could avert war.

With his health failing, FDR went to Warm Springs on March 30 to attempt to recover his strength. There he would write his “Jefferson Day” radio address, scheduled for April 13. He died on April 12.

With his powers of personal diplomacy failing, Roosevelt bequeathed to all of us the hope that what he knew about “science of human relationships” could be invested in a world organization. The fate of the Jews of Europe, like so much unfinished business of the Second World War, would fall to the United Nations. There has been no end to war, but neither has there been a Third World War.

Sources

Bohlen, Charles E. Witness to History: 1929-1969. New York: W.W. Norton, 1973.

Breitman, Richard and Allan J. Lichtman. FDR and the Jews. Cambridge: Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 2013.

Coppola, John. “A Pride of Museums in the Desert: Saudi Arabia and the ‘Gift of Friendship’ Exhibition,” Curator 48/1 (January 2005): 90-100.

Freidel, Frank. Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Rendezvous with Destiny. Boston and New York: Little Brown, 1990.

Lippman, Thomas, W. “The Day FDR Met Saudi Arabia’s Ibn Saud,” The Link (April-May 2005):1-13.

Rosen, Robert. N. Saving the Jews: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Holocaust. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2006.

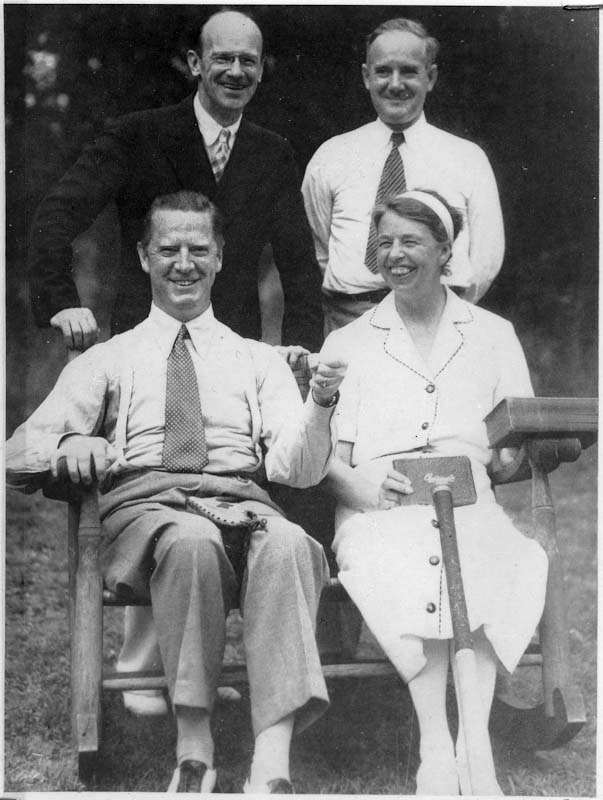

Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson upon arrival in Japan, May 22, 1953.

Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson upon arrival in Japan, May 22, 1953.