What the Titanic Can Teach Us About Surviving Climate Change

by Michael Weishan

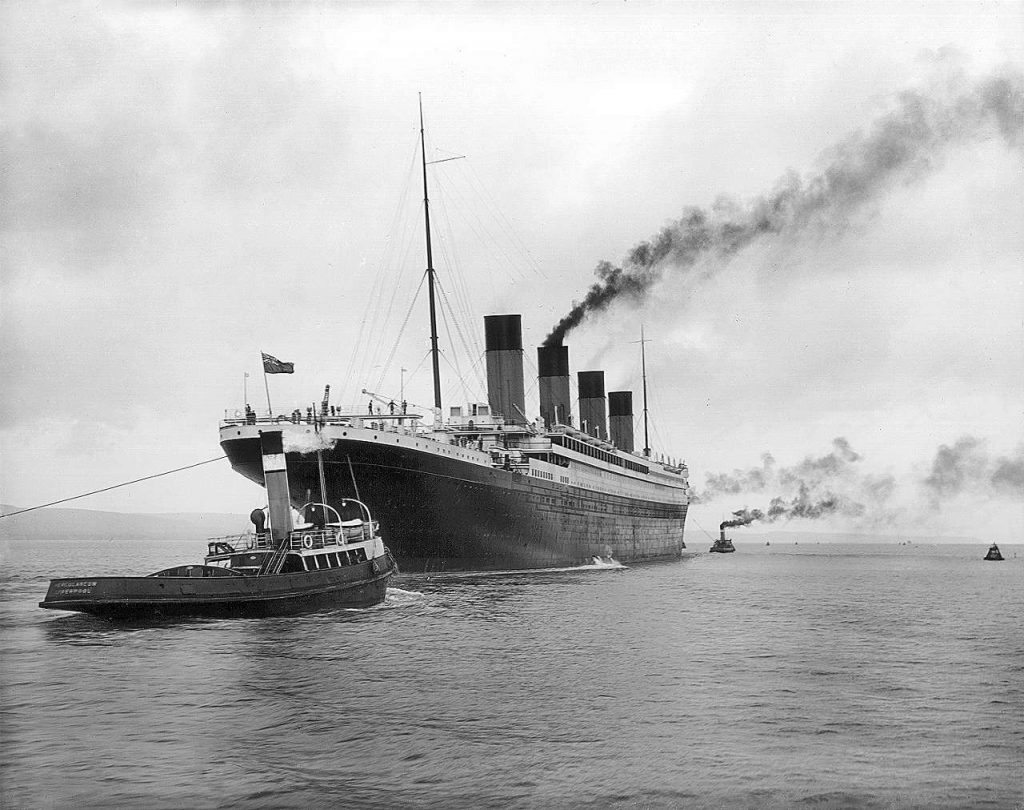

The Titanic leaving Belfast shipyard, one day old. Exactly two weeks later she would lie on the bottom of the Atlantic.

The time is 11:39 PM April 14, 1912 and the largest moving object mankind ever created is about to rendezvous with destiny.

In a little more than 60 seconds, a several-thousand-year-old piece of ice will scrape along the hull of a two-week old liner named Titanic [all external links are to wikipedia unless noted], dooming the glittering pride of the White Star Line. She carries on this her maiden voyage 885 crew catering to 1317 pampered passengers, with just 20 lifeboats, enough to hold roughly half of those on board. Why so few? A little noticed lobbying effort a decade earlier by the major shipping lines had successfully argued that lifeboats (expensive to build and maintain, and worse, consuming revenue-generating deck space) were unnecessary in an era of water-tight doors and wireless communication. Modern technology, shipwrights claim, render their vessels virtually unsinkable, a view shared by three of the most competent nautical experts of the age, now hastily summoned to the bridge of the suddenly silent liner. In command is Captain Edward Smith, the commodore of the White Star Line. His presence aboard this crossing is intended as an honorific farewell: on reaching New York, he will retire from a largely uneventful 50-year career at sea. With him, naval architect Thomas Andrews, the ship’s designer, aboard to fine-tune last-minute details and make notes for improvements to the Titanic’s two sisters, the earlier Olympic, and a behemoth still in the ways, to be christened Gigantic. Finally, the man who had envisioned and willed this transatlantic trio into existence, J. Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line. These three, with a over a century of nautical expertise shared between them, know more about the Titanic than anyone else on earth.

Yet despite this vast know-how, they are utterly powerless to alter their shocking circumstances: having quickly surveyed the ship after the collision, designer Andrews reports to a stunned Smith and Ismay that the Titanic will be on the bottom of the Atlantic within two hours.

Setting aside this tragic narrative for a moment, let’s examine our own present situation, as we recently did at the “Beyond Tomorrow: Safeguarding Civilization Though Turbulent Times” conference at Harvard University in October 2015, co-hosted by the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation and El Camino Project [link to external site]. Speaker after speaker, Ambassador Bruce Oreck, ethnobotanist Mark Plotkin, and NASA historian Erik Conway among others warned that we, as a nation and as a planet, are in dire trouble; embarked on a one-way journey that will end at best badly, and at worst tragically; and that we now face critical choices that must be met with courage and resolve. A ripple of disquieting realization washed over the conference participants, many of them students just beginning their lives, as each struggled to find a balance between optimism and pessimism, hope and despair. Surely, many asked, it can’t be as bad as all that?

Captain Edward Smith

The reaction was eerily the same that starlit April night in 1912. Early on, before the Titanic’s wounded bow began visibly settling into the 29º F water of the Atlantic, few passengers cared to leave the glowing decks for the dark cramped lifeboats now dangling from the davits. (Had the passengers known there had never been an evacuation drill and that many crewmen were unfamiliar with the process of lowering the boats, even more would have resisted.) As it was, the first few lifeboats were lowered pitifully under-filled, most of the passengers preferring to wait in the luxurious warmth of the library, the smoking room or the grand first class stairway, where the large clock portraying “Honor and Glory Crowning Time” relentlessly tick-tocked down the seconds, poignant counterpoint to the beat of the ragtime tunes being played by the ship’s orchestra. It was a scene of surreal calm, the last moment of peace many there assembled would ever know.

Thomas Andrews

“Surreal calm.” Does that strike a foreboding yet familiar note? Down deep, most of us know that our planet is in trouble. Whatever your political stripe, your belief set, or whether you think the sea will rise 2 inches, 2 feet, or 10 feet over the next century, all you have to do is take a critical look around — like Thomas Andrews — and “sound the ship” to realize the proverbial engines have stopped and we’re taking on water. A sampling of alarming facts:

-

- 80% of the Earth’s original forests are now gone, and in the Amazon alone we lose 2000 trees a minute.

-

- 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic are now distributed across the world’s oceans, with a half-life that exceeds hundreds of years for many types of debris.

-

- The desert has claimed one-third of the globe and is advancing into fertile dry lands on four continents.

-

- Species extinction has risen from a normal rate of 1-5 per year to 20 per day. By 2050 half of all Earth species will be threatened.

-

- Because of increased C02 uptake, the pH of the world’s oceans has fallen from 8.2 to 8.1, a 25% increase in acidity. By the end of the century, ocean pH is projected to reach 7.8. Fossil records reveal that such drops have previously triggered global mass extinctions.

-

- While energy demand in the West is projected to remain relatively flat, global energy demand will increase by 70% in the next 25 years due mostly to a rise in developing-world consumption.

- By 2050, even with sustainability initiatives in place, the human race will need 50% more energy, 40% more water, and 35% more food.

Of course, the great unspoken bugaboo behind all these figures is overpopulation, but few of even the most vocal climate change campaigners dare address this topic, and certainly none of our current crop of spineless politicians has the courage to do so. The issue is far too politically and religiously charged, and telling ugly truths never wins votes. But no prescient talent or special technological expertise is required to understand that adding an additional 3-4 billion people to our planet in the next several decades will overwhelm an already overburdened ecosystem. Even if climate change were entirely dismissed, these and many other indicators from across the planet show that the planet simply can’t maintain 10 billion humans, each trying to increase his or her share of a petroleum-soaked consumer-driven pie.

Add effects of climate change back into the picture, with millions of people from Boston to Bangladesh displaced by flooding and storms; critical infrastructure like our antiquated electric grid crippled; food supply distribution networks disrupted or destroyed by climate-induced sectarian strife; and vast tracts of formerly bountiful farmland in the American West, Central China and Northern Africa reduced to desert, nd you have an almost 100% surety of societal collapse. To quote lines from James Cameron’s movie version (link to imdb.com) of the Titanic tragedy:

J. Bruce Ismay

Ismay: [incredulously] But this ship can’t sink!

Thomas Andrews: She’s made of iron, sir! I assure you, she can…and she will. It is a mathematical certainty.

Let me then be equally clear: The Western lifestyle we enjoy in America in 2015 simply cannot be sustained, and it especially cannot serve as a model for the developing world. It is “a mathematical certainty.”

We have at last met our iceberg, and it is us.

So now what? Will it be “women and children first” as they did on the Titanic, or infinitely more likely in this self-centered age, “every man for himself?” As our species faces the grim realities, we can benefit from the lessons learned on a doomed transatlantic liner in 1912.

First and foremost: we must candidly and immediately acknowledge the full extent of the crisis.

Given their staunch Edwardian belief in the infallibility of human progress, Captain Smith, Andrews and Ismay may be forgiven for doubting that their “unsinkable” wonder could founder beneath their feet. One minute all was well, and the next, disaster. Yet the ship’s command quickly and accurately assessed the situation, overcame very powerful disbelief — especially hard because physical manifestations of the growing tragedy were not yet generally visible — and made the critical decision to abandon ship. At best, this would mean a highly perilous operation, which would subject passengers to a harrowing descent 70 feet down the side of the ship in tiny open boats only to strand them a thousand miles from shore in a freezing sea, surrounded by icebergs. If for some reason they were wrong, that things weren’t as dire as Andrews believed and the ship somehow remained afloat, they would have subjected their passengers to a potentially fatal ordeal that would destroy the reputations of all three men and damage the White Star Line irreparably.

But Smith did not hesitate. The order came to lower the boats, and it was this rapid acknowledgment that the impossible was in fact probable that saved the 710 passengers who eventually made it to New York. Despite the risks, despite the incredulity, despite the open resistance from passengers, one by one tiny boats began to drop into the frigid North Atlantic. Companion to this dreadful acknowledgment was another more frightful realization, silently admitted by only a select few, but equally valid today: not everyone would be saved, but every second spent in denying the realities of the present meant even more casualties. Our Internet-linked society has no excuse to deny or ignore the severity of our ecological crisis. Unlike those in 1912, we can see the iceberg. In fact, we’ve known about it for decades. We, in 2015, must follow the example of these three men: we must admit that the impossible has occurred and begin to make our plans based on worst-case scenarios, not the best. This was the basic premise explored at the Beyond Tomorrow conference.

We cannot use looming disaster as an excuse to do nothing.

In the Victorian era, the model of gentlemanly sangfroid was to meet one’s fate with silent resolve and grim reserve. But to modern eyes, going down with the ship simply yields another corpse. Picture millionaire Benjamin Guggenheim, who returned to his cabin, donned formal gear, and told everyone who would listen that he and his valet (who seemingly was offered no other choice) “we’re dressed in our best and prepared to go down like gentlemen.”

Really? Was that all a gentleman could do, dress in white tie and tails to passively await the end?

Hardly.

Benjamin Guggenheim and valet awaiting their fate in James Cameron’s movie version, Titanic.

History is pretty clear on this point: fortune favors the brave, and the brave favor action. As members of our planet’s privileged educated elite, we all become Benjamin Guggenheims when we intellectually acknowledge the coming crisis, but continue our carbon-soaked lifestyles unabated and unaltered, on the theory that we will either be dead before the worst comes, or, that small changes won’t matter anyway, so why bother? Small changes DO matter, then and now. On the Titanic, witness all those who fought to free the last collapsible lifeboats; or who like the artist Frank Millet, went below decks to aid steerage passengers who didn’t speak English; or the wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, who stayed at their posts frantically signaling for aid until the power failed minutes only minutes before the ship foundered. Even a few of the passengers already in the lifeboats rose to the fore, including the soon-dubbed “Unsinkable” Molly Brown, the rough-and-tumble Colorado mining heiress who shared her ample clothing with shivering survivors, took an oar to help row, and then verbally bullied the lifeboat’s reluctant crew until they agreed to return and search for survivors in the water. None of these valiant actions altered the trajectory of the main event, but they did mitigate the degree of the disaster in many ways. Those who were saved, were saved through action, not inaction.

The same is true today. While truly “sustainable” environmental policies are a myth (sustainability is defined as “continuing indefinitely” and no current technology or program comes even close to meeting that mark) the net effect of these initiatives is positive as long as they don’t lull us into believing that the crisis isn’t upon us. The water is still creeping up the decks, but every direct action that attempts to mitigate the problems confronting us multiplies the scope of possible outcomes exponentially.

Don’t depend on technology to rescue us.

One Beyond Tomorrow participant, New York Times columnist David Brooks [link to NY Times], expressed a commonly held skepticism about doomsday scenarios. “Challenges to civilization have occurred before, and always something comes along to save the day,” he stated. Many people clearly want to agree, cherishing the hope that some sort of technology will be invented to reverse global warming or drastically lower carbon emissions. This is a conveniently comforting sop, which we must immediately abandon.

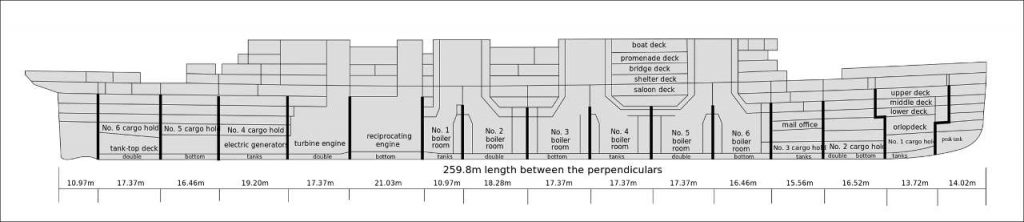

The plan of the watertight doors on the Titanic, indicated by the bold vertical lines. The ship could remain afloat with first four watertight compartments flooded, which Andrews imagined the worst possible outcome of a direct head-on collision. The iceberg however had other ideas. Skipping along the hull of the ship, it damaged each of the first five compartments, cutting just far enough along the hull to allow the sea to spill from one compartment to another, dragging the ship down by the bow. Human technology has a poor track record when pitted against the forces of nature.

The Titanic clearly demonstrates the fallacy of putting too much credence in miraculous salvation. Repeatedly Captain Smith and others aboard the doomed liner thought they saw the lights of a ship just over the horizon, and they tried everything they could think of to signal this phantom-like vessel — Morse lamp, rockets, wireless. All in vain. The mystery ship, the Californian, was indeed there, just 10 aching miles away, but her commander inexplicably dismissed the Titanic’s signals as “company flares.” (Why any liner would be sending up gratuitous rockets mid-ocean he never explained.) Even worse, the Californian had a sole radio operator, asleep in his cabin when the distress calls came through. If the passengers and crew of the Titanic had hesitated to board and launch the lifeboats, expecting instead salvation from that almost tangible glimmering hope, no one would have survived the sinking at all. Yes, it’s possible some future technological advance may save us from ourselves at the last minute. It’s equally possible one won’t. We can’t afford to wait and see.

Don’t expect our national leaders to save the day.

After the grim decision to lower the boats, the three men most responsible for safety of the Titanic reacted in remarkably different ways. J. Bruce Ismay, who early on helped passengers into the lifeboats, inexplicably hopped into one himself and stepped off the deck of his sinking ship with thousands still on board. Captain Smith, after an initial burst of decisive action, became unresponsive and withdrawn as critical decisions mounted, and was last seen standing alone on the bridge, silently waiting as the water crept over the raised threshold of the wheelhouse. Thomas Andrews did what he could, going from stateroom to stateroom, urging passengers into the boats. According to one survivor’s testimony, he met his end in the smoking room, staring into a painting over the fireplace ironically entitled “Approach to the New World.” Another account has him frantically throwing deck chairs into the ocean to use as floats. Regardless, over a thousand people remained clinging to the rapidly sloping decks, and all but a few would be dead within the hour. The lesson here is clear. When confronted with overwhelming crisis, the leaders we so depend on may be unable to act effectively, and it falls to individuals and small groups to save themselves and others.

A perfect example: our own US government’s dysfunctional response when confronted by the early and evident signs of climate change as much as 40 years ago, a response which remains woefully lacking today. Democratic and Republican administrations alike might have moved decisively on environmental legislation when it could have been highly effective, but failed to act, as both parties were (and continue to be) held captive by special interests that reap huge short-term profits from the status quo. This same paralysis is evident across the globe, as time and time again world leaders sound an alarm, then fail to agree to practical steps. However, as our speaker Dr. Erik Conway pointed out, local, state and regional initiatives have been proven highly effective in changing national and international patterns of behavior. Dr. Conway cited California’s insistence on cleaner emissions standards for cars; this legislation, which was fought by auto manufacturers for decades in the courts, was eventually upheld. Loath to lose the lucrative California market, the manufacturers gave in, and shortly thereafter these rules became the national standard. Corporate America reacts to one thing only, the almighty dollar, and if enough dollars move to one side of the scale, even the most reluctant corporate players will switch sides. Another example: the organic/local food movement, which was pooh-poohed by government and business alike 30 years ago, but because of bottom-up pressure by consumers has become an important force that now shapes issues of health and lifestyle, as well as affecting economic decisions about land use and urban planning across the US and Europe. It’s clear that micro actions like these, especially when backed by purchasing power, often can and do have macro effects.

Lastly, don’t allow civilization to become another casualty.

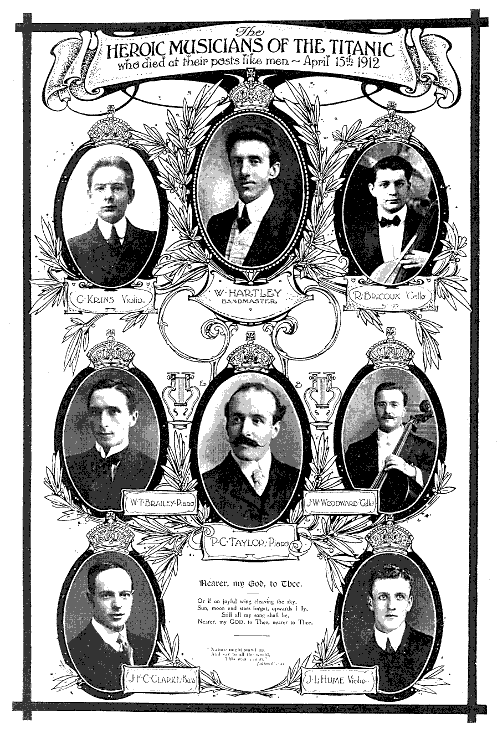

In times of crisis, especially when human lives are at stake, it’s easy to push thought of saving elements of our culture — history, the arts, music, literature, language — to the side. But it is these very elements that constitute our human civilization, which, along with the rule of law, form the basis of the liberal Western democracy we enjoy. The value of art in a time of tragedy was clearly demonstrated on the Titanic by members of the ship’s band who calmly set up their instruments on the open deck as the lifeboats were loaded all around them. One might be excused in thinking that this was done from duty: they were crew after all. But they weren’t, which makes their actions all the more noteworthy. The White Star Line, in an effort to save money, carried them as private contractors in 2nd class. As such, these eight men had as much right to save themselves as any other passenger, but instead remained and played, according to many survivor accounts, until the decks became too steep to stand upon. The scene must have been almost unimaginable: the brilliantly illuminated Titanic, sinking by the bow into an absolutely flat black sea, so calm in fact not a crest rippled the mirror of a million stars that crystal night. There is absolute stillness other than the low rumble of people on the decks, punctuated by the shouts and creaks of the davits being lowered, and the periodic report as emergency flairs whistle into the sky, burst, then fade. Suddenly, through the frigid air, clearly audible to those on deck and even to those a quarter-mile away in the boats, arrive the first cheering notes of the “The Merry Widow’s Waltz,” the jaunty beat of ‘“Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” “Silver Heels,” or “Waiting for the Robert E. Lee,” and then, towards the end, more somber tunes like the wistful serenade “Songe d’Automne.’” Almost every survivor account mentions the music, and the effect this had in suppressing panic almost to the end: while the music lasted, hope remained. The eight musicians of the Titanic knew this instinctively, and because they did, surrendered their lives to a man. Music, the arts, literature, history — these are the elements that bind the veneer of civilized behavior to our lesser natures. As a species, we move forward without them at our utmost peril.

The sad truth is that no single resolve will get us off the fateful voyage we’ve embarked on. Like the passengers on the Titanic, we’ve long since left the safety of the harbor, and now we find ourselves in peril mid-ocean, without hope of external rescue. Today, our Titanic is the planet, our sea, this empty part of the universe, where we are truly alone. And like those luckless souls of a century ago, it’s becoming rapidly clear to even the most ardent naysayers that we’re not going make our intended landfall.

Lamentably, we brought this tragedy on ourselves, and we will have to endure it to the end. But how we survive, how many survive, and how well, is still up to us.

Time to man the boats.

One of the Titanic’s lifeboats as photographed from the rescue vessel Carpathia, April 15th 1912.

Author, historian and PBS Host Michael Weishan is the Executive Director of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation at Harvard, a co-sponsor, with El Camino Project, of the Beyond Tomorrow Conference at Harvard University, October 16-18 2015.

©2015 Michael Weishan, all rights reserved.