Demagogues and Democracy

The specious promises of the prophets of an unearned plenty are a mirage which beckons and lures us, not to the millennial city, but into the deserts of disillusion and ruin. And perhaps we shall even lose our liberties on the way.

-Winston Churchill, “Soapbox Messiahs,” 1936

Out of office during the 1930s, Winston Churchill devoted himself to—and earned his living from—writing. In this piece from the June 20, 1936, issue of Colliers, a popular opinion magazine of the time, Churchill’s critique of the leading American demagogues of the Depression—Huey Long, Father Charles Coughlin, and Dr. Charles Townsend—warned that the magical thinking that “some great new world is going to open where work will do itself, and where ‘something for nothing’ is the order of the day” was nothing but a “mirage” (p. 11). A firm believer in capitalism (and democracy), he lambasted those who would turn to communistic or fascistic solutions to address the worldwide financial crisis. Echoing the optimism of Franklin Roosevelt, with whom he would forge the Anglo-American special relationship a few years later, Churchill declared, “I believe that prosperity will return. I believe that the greatest days of that system of private enterprise which has done so much for the world in the past century lie in the future and not in the past. But the gains of tomorrow can be won only by thought and effort” (p. 46).

These are not the words of a demagogue. They speak of hard work and sacrifice and to those facing starvation and homelessness, they offer no immediate solutions. Much more alluring in times of uncertainty and despair, are the charms of the demagogue. He (and most of the time, but not always, a demagogue is a he) promises easy solutions to complicated problems using dubious methods. He stirs up people’s passions and fears with exaggerated rhetoric and scapegoating. Slogans, name calling, and misrepresentation are his stock in trade. And most of all, he cajoles people into believing that he and only he can solve their problems—often turning himself into a messianic figure who commands “emotional attachment to his person” that “effectively block[s],” in the words of David H. Bennett in his book Demagogues in the Depression, “any group awareness of either the real sources of unhappiness or the real means of solution” (p. 4).

Demagogues have a long history associated not only with suffering and deprivation, but with the very foundations of democracy. Perhaps it is because only in democracy do ordinary people dare to believe that their lives can be better. That seductive dream opens the door for the demagogue. The word itself derives from ancient Greek and means quite simply a leader who espouses the cause of the common people. Plato’s Republic suggests a more sinister meaning in Book VIII: “[T]yranny is . . . established out of no other regime than democracy . . . the greatest and most savage slavery out of the extreme of freedom.”

Dr. Michael Leib of Philadelphia,

an Antifederalist

In the United States, by the 1790s our first demagogues were appearing in “democratic societies,” which opposed the strong central government and elitism of the Federalists. Many were idealistic democrats inspired by Thomas Jefferson and the French Revolution; others more easily fit the contemporary description of “mob-masters” who, as described by Reinhard H. Luthin in “Some Demagogues in American History,” eschewed gentlemanly decorum for rabble rousing. As we know all too well, the Founders—well-born, educated gentlemen—carefully restricted voting rights in the Constitution to white men with property, judging the restriction of suffrage (in the words of John Dickinson) a “defence against the dangerous influence of those multitudes without property and without principle with which our Country like all others, will in time abound.” But it was Dickinson’s home state of Pennsylvania that alone had extended voting to white men without a property requirement in its first state constitution.

Luthin’s first American demagogue was Dr. Michael Leib of Philadelphia, an Antifederalist who was “selfish and ambitious . . . [with] a spitfire eloquence that ‘produced effect rather by the velocity of his missiles than the weight of his metal’” (p. 23). And like many who were to follow, while expressing concern for the welfare of the masses, Leib “lived luxuriously, powdered his hair, wore ultrafashionable dress, and sprayed himself with perfume, just like the hated Federalists.” He nonetheless “convinced the humble” he was “one of them” and won a seat in the U.S. Senate. The idea of universal [white] manhood suffrage spread and as the “era of the common man” took hold in the 1820s, a long parade of American demagogues began. They were, according to Luthin, “confined neither to a single political party nor to a particular social viewpoint nor to one section of the country” (p. 4). Michael Leib was followed by Antimason Thurlow Weed, then by the Jacksonian Democrats Franklin E. Plummer, Richard M. Johnson, and Ely Moore. Anti-Jacksonian Whigs like Tom Corwin were followed by antislavery Republicans like James H. Lane, Nathaniel P. Banks, and Thaddeus Stevens, who in turn railed against proslavery Democrats Albert Gallatin Brown, Henry A. Wise, Louis T. Wigfall, Joseph E. Brown, and William L. Yancey. Later we had the Tammany Democrat Fernando Wood, Anglophobe Republican Richard J. Oglesby, and a host of “bloody-shirt” Republicans like Ben Butler, James G. Blaine, and William A. Wheeler, to name a few. In the South populist-Democrats sprang up in the 1870s with Ben Tillman, followed by Tom Watson and Jim Hogg in the 1890s, and Jim Vardaman, Eugene Talmadge, Jim Ferguson, and Theodore G. Bilbo into the early twentieth century. Together they round out a partial list of demagogues in American history. It should not be overlooked that historian Lutkin was doing his research during the rise of Senator Joseph R. McCarthy in the early 1950s.

Demagoguery reached new heights in the 1930s. Hitler rose to power in January 1933 and Mussolini consolidated his totalitarian empire. Each promised to right the wrongs—economic as well as nationalistic—that had plagued Germany and Italy after World War I. In the United States, a host of extremists emerged in those grim days. Father James R. Cox led the Jobless Party in 1932 and William H. “Coin” Harvey organized the Liberty Party in the same year. In 1933 William Dudley Pelley founded the Nazi-like Silver Shirts Legion in America and another admirer of Hitler, “General” Art J. Smith, organized the Khaki Shirts. Philip Johnson and Alan Blackburn, also fascists, began their National Party in 1934. There were also Alexander Lincoln and his Sentinels of the Republic, George E. Deatherage and the Knights of the White Camellia, and self-styled fascists Seward Collins and Gerald Winròd (Bennett, p. 4).

The four demagogues who formed the Union Party in the summer of 1936 were another story. Each had reached national prominence in his own right and together they—and their many followers—believed they stood a chance against Franklin Roosevelt: Father Charles E. Coughlin, the “radio priest” from Royal Oak, Michigan; Dr. Francis E. Townsend of Long Beach, California, creator of the Old Age Revolving Pension Plan; Gerald L. K. Smith of Louisiana, who inherited the mantle of Huey Long’s Share Our Wealth plan after Long’s assassination; and Congressman William Lemke of North Dakota, a long-time activist on behalf of farmers of the northern Great Plains. They were unlikely political bedfellows, but they had two things in common: each believed in Robin Hood-like panaceas to the Great Depression that would take money from those who had it and give it to the poor; and each, for his own reason, hated Franklin Roosevelt.

******

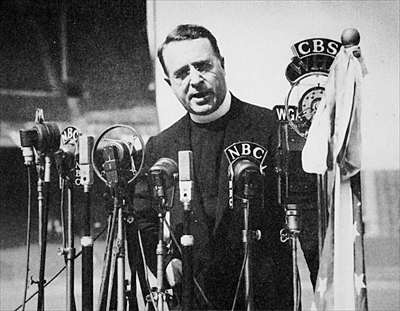

Father Coughlin

[N]o candidate who is endorsed for Congress can campaign, go electioneering for, or support the great betrayer and liar, Franklin D. Roosevelt. . . . I ask you to purge the man who claims to be a democrat from the Democratic Party—I mean Franklin Double-Crossing Roosevelt.

Father Charles Coughlin, Townsend Plan Convention, Cleveland, July 1936

Father Charles Coughlin, the “radio priest.”

The Reverend Charles E. Coughlin, the “radio priest,” built a radio following in the late 1920s from his pulpit at a small parish church in Royal Oak, Michigan. Born in Hamilton, Ontario, to Irish Catholic parents, Coughlin began his religious life in Canada but moved to the U.S., where he was assigned to lead the Shrine of the Little Flower of Jesus—a newly established temple to St. Thérèse, a recently canonized French Carmelite nun. Located in a poor industrial suburb of Detroit with few Catholics, the Ku Klux Klan harassed the parish with burning crosses. Anxious to expand and build support for his church, Coughlin began delivering sermons on the radio in 1926 and organized the Radio League of the Little Flower to solicit contributions. With radio in its infancy, and Coughlin’s extraordinarily mellifluous voice, the fundraising was enormously successful. He raised more than enough money to support and expand the shrine, along with his growing staff and radio expenses, and became a celebrity.

After the stock market crash in October 1929, Coughlin added politics and economics to his radio sermons, railing against big banks, bankers, and “Godless Communism” as responsible for the woes of his working-class listeners. He purchased radio time in Chicago and Cincinnati, in addition to Detroit, and by 1930 was reaching a national audience. He attacked Herbert Hoover as “the banker’s friend, the Holy Ghost of the rich, the protective angel of Wall Street.” His popularity soared. “Hoover Prosperity Breeds Another War,” brought him 1.2 million letters (Bennett, p. 34). Before long Coughlin was receiving an average of 80,000 letters a week and employing 96 mail clerks. (Early in his presidency Roosevelt received about 50,000 letters a week.) Reflecting his own Irish Catholic heritage and that of his substantially Irish and German Catholic audience, Coughlin was an Anglophobe and highly influential among Roman Catholics in New England, the Northeast and Midwest—a constituency important to Roosevelt. Coughlin supported FDR as a candidate and early in his presidency, calling the New Deal “Christ’s Deal,” until the president moved to distance himself when Coughlin’s attentions became too effusive and the priest began to see himself an economic advisor.

In the middle of his fiery speech at the Townsend Plan convention in Cleveland, 1936, Father Coughlin dramatically stripped off his clerical collar and black coat before a crowd of 10,000.

The break between Coughlin and Roosevelt came after late 1934 when Coughlin declared the old political parties “all but dead” and should “relinquish the skeletons of their putrefying carcasses to the halls of a historical museum” and announced formation of his political organization, the National Union for Social Justice. Large numbers of local units, organized by congressional district, were to be the “lobby of the people” to pass legislation consistent with his Sixteen Principles, which abolished the Federal Reserve and replaced it with a central bank and called for the nationalization of key industries and protecting the rights of labor. By April 1935 Coughlin claimed 8.5 million people had expressed support for the Sixteen Principles. By the following January, he announced “at least” 5,267,000 new members in 26 states and 302 of 435 congressional districts.

A vocal isolationist, at the end of January 1935 Coughlin preached against the “menace of the World Court” as well as “international bankers” who, as David Kennedy explains in his book Freedom From Fear, were the alleged beneficiaries of Roosevelt’s nefarious plan to involve the United States in overseas affairs (pp. 232-34). (Roosevelt himself misread the peoples’ temper and thought it an opportune time to reintroduce the country to internationalism.) Prodded also by the Hearst newspapers, hundreds of thousands of telegrams filled the Senate mailroom and the World Court treaty was defeated by a narrow margin. As Kennedy reports, Louisiana Senator Huey Long declared, “I do not intend to have these gentlemen whose names I cannot even pronounce, let alone spell, passing on the rights of the American people” (p. 233). After the 1936 election, Coughlin became a vocal anti-Semite, blaming Jewish bankers for the Russian Revolution as well as world financial crises. To oppose Communism he increasingly expressed sympathy for Hitler and Mussolini. Coughlin’s broadcasts were substantially silenced after the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 when he was forced off the air. He continued to push his anti-intervention views in his magazine Social Justice until after Pearl Harbor when, threatened with revocation of his mailing privileges and a likely sedition trial, the Roman Catholic Church finally silenced him.

Gerald L. K. Smith (and Huey Long)

I’ll show you the most historic and contemptible betrayal put over on the American people. . . . Our people were starving and they burned the wheat . . . hungry, and they killed the pigs . . . led by Mr. Henry Wallace, Secretary of Swine Assassination . . . and by a slimy group of men culled from the pink campuses of America with a friendly gaze fixed on Russia . . . beginning with Frankfurter and all the little frankfurters. . . . They told the workers to organize under section 7a, and the U.S. government became the biggest employer of scab labor in the world . . . and they had the face to recognize Russia, where two million Christians had been butchered and the churches were still burning. . . . This election to me is only an incident. . . . My real mission is to see that the red flag of bloody Russia is not hoisted in place of the Stars and Strips—Give me a hand!

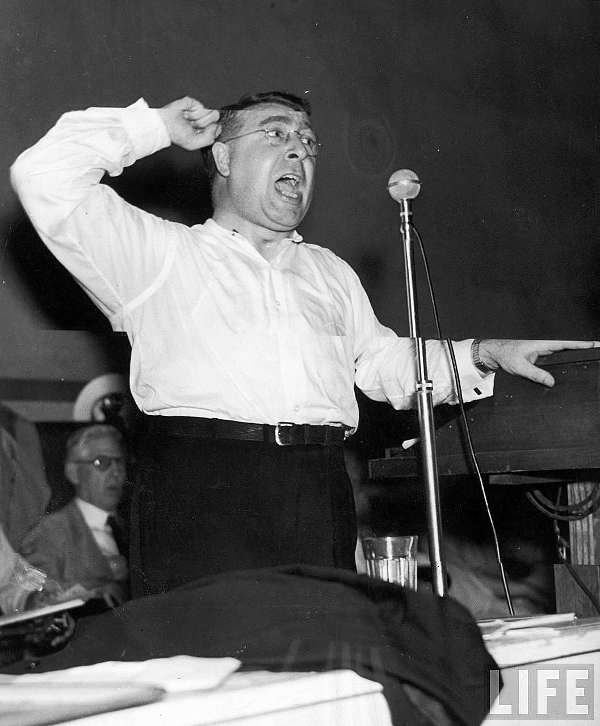

Gerald L. K. Smith, Cleveland, 1936

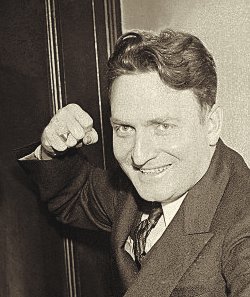

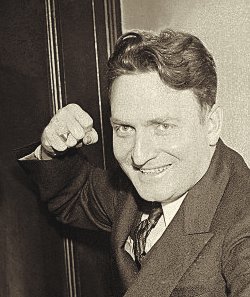

Gerald L. K. Smith

“I’ll teach ‘em how to hate.”

Gerald L. K. Smith’s Cleveland speech took place at Coughlin’s National Union for Social Justice convention in August 1936, one of two meetings that summer that forged the alliance of protest movements into the Union Party. Smith was heir to Huey Long’s Share Our Wealth Plan and Huey Long was the one demagogue who seriously worried Franklin Roosevelt. FDR called him “one of the two most dangerous men in America.” The other, he later added, was General Douglas MacArthur (Brinkley, p. 57). Long was governor, then senator, from Louisiana where his powerful machine won popular support by implementing long-overdue improvements in public health, education, road-building, and public works. He was from the poor hill country of northern Louisiana (although his family was reasonably prosperous) and built his power base on the disaffected, populist sentiments of that region’s tenant farmers. Known as the Kingfisher, he had become the virtual dictator of Louisiana when he resigned as governor in 1932 to become senator.

Long’s Share Our Wealth Plan called for deeply graduated, confiscatory income and inheritance taxes designed to redistribute large fortunes to the citizenry at large. Every American family would be guaranteed a “household estate” of $5,000, “enough for a home, an automobile, a radio, and the ordinary conveniences,” and a government guaranteed annual income of from $2,000 to $2,500 (Brinkley, p. 72). Share Our Wealth clubs proliferated throughout the South and by mid-1935 were in many other regions as well.

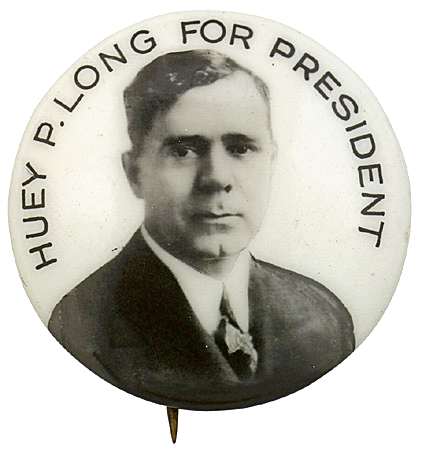

Huey Long for President lapel button.

At first Long supported Roosevelt, but later he became an opponent as his own aspirations for the presidency became clear. Roosevelt sought to undermine Long’s influence by denying him patronage and launching an investigation into alleged tax fraud in the Long organization. Democratic politicians warned Roosevelt that Long was a threat to the New Deal coalition and that he was planning a third party run. Roosevelt was sufficiently worried that in 1935 he had the Democratic National Committee prepare a statistical report on the two most prominent demagogues—Father Coughlin and Huey Long (Bennett, p. 80). But the threat from the latter came to an end when Long was assassinated in September 1935.

Gerald L. K. Smith, a clergyman who was national organizer of the Share Our Wealth Society, continued Long’s national political plans; but where Long had been largely noncommittal on race, Smith took the Share Our Wealth Society in new racist (and anti-Semitic) directions. Like Long and Coughlin, Smith was a bombastic orator, memorable for some of the most sensational (and frightening) rhetoric of the era:

I’m not a teacher. I’m a symbol—a symbol of a state of mind. When the politicians overplay their hand, certain nerve centers of the population will begin to twitch. The people will start fomenting and fermenting, and then a fellow like myself, someone with courage enough to capture the people, will get on the radio, make three or four speeches, and have them in his hand. I’ll teach ‘em how to hate. The people are beginning to trust true leadership. (Bennett, p. 142)

Smith formed the American First Party in 1943 and ran for president as an isolationist in 1944. He was a member of William Dudley Pelley’s pro-Nazi Silver Shirts organization, patterned after Hitler’s brown shirts. After the war he advocated for the release of Nazi war criminals convicted at the Nuremburg Trials and continued as an activist in far right politics.

Francis E. Townsend

We dare not fail. Our plan is the sole and only hope of a confused and distracted nation. . . . We have become an avalanche of political power that no derision, no ridicule, no conspiracy of silence can stem. . . . Where Christianity numbered its hundreds in its beginning years, our cause numbers in its millions. And without sacrilege we can say that we believe that the effects of our movement will make as deep and mighty changes in civilization as did Christianity itself.

Francis E. Townsend, Time, November 4, 1935

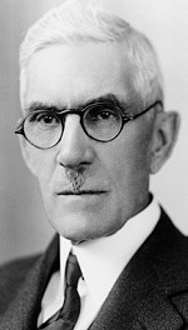

Dr. Francis Townsend in 1935.

The third mass movement of the 1930s was the Townsend Old Age Revolving Pension Plan founded in 1933 by an elderly and mild-mannered medical doctor from Long Beach, California. By spring 1936 it had between 2 and 3.5 million paying members (dues were 25¢) organized into more than 4,500 local Townsend Clubs. Its members were the elderly, people for whom the Depression struck particularly hard as their life’s savings were lost in the bank crises—and jobs, even for the young and able-bodied, were hard to come by. Social changes played a role, too. With multigenerational families dispersed by the demands of the new industrial economy, the traditional social safety net was stretched thin. It is not surprising, then, that the movement started in southern California, which was already a retirement mecca with the elderly living far from their families. Frightened and desperate, they were ready for a savior.

Dr. Townsend seemed an unlikely demagogue, but possessed of an idea and a cause he nevertheless became one. His fanatic followers were devoted to him as a savior and he did not disabuse them of the notion.

Born in 1867 into a poor but religious farm family in rural Illinois, Townsend tried farming and school teaching before enrolling in medical school, receiving his degree at age 36. He practiced medicine in the Black Hills of South Dakota for 15 years, served as a medical officer in World War I, and moved to Long Beach in 1919. To supplement his medical income in California, he speculated in real estate sales, and was appointed a county public health officer in 1930. Then he too lost his job and was thrown back on dwindling savings. Appalled by the poverty of the elderly, he determined to take action. He was 66 years old when he wrote an opinion piece for his local newspaper, the Long Beach Press-Telegram, setting forth his plan to provide a “revolving” pension for the elderly.

It is estimated that the population of the age of 60 and above in the United States is somewhere between nine and twelve millions. I suggest that the national government retire all who reach that age on a monthly pension of $200 a month or more, on condition that they spend the money as they get it. This will insure an even distribution throughout the nation of two or three billions of fresh money each month. Thereby assuring a healthy and brisk state of business, comparable to that we enjoyed during war times.

Townsend Plan billboard.

To Townsend and his followers, it was simple and perfect: the original plan was to be funded by a “transaction” or sales tax on all business transactions—wholesale and retail—that would stimulate the economy. He called it the “velocity of money” and it would sweep away the Depression. With the aged withdrawn from the workforce, Townsend predicted that “millions” of jobs would be created, and state and local governments would save on the costs of almshouses, prisons, and policing as poverty was eliminated. He worked with his old boss Earl Clements, a real estate marketer, who masterminded the publicity machine and membership program that turned the Townsend Plan into a national movement in a matter of months. It was phenomenally popular. At one point club members conducted a letter-writing and petition-signing campaign to secure congressional approval of a bill to institute the plan. In a matter of three months, twenty million signatures (one-fifth of the adult population) were collected, a demonstration of public support “unmatched in history”—exceeding support for the soldiers’ Bonus Bill or opposition to the World Court, which were “mere rivulets compared with this torrent.” But even with this massive support, and subsequent revisions, the measure did not pass (Bennett, p. 174).

When Roosevelt refused to meet with him, Townsend was miffed. A more serious problem was the Social Security Act with its $30 a month old age insurance, which Townsend and his followers thought a devious distraction designed to take support away from the Townsend Plan. The Townsend movement grew in strength after passage of Social Security in 1935 and many historians credit the Townsend Plan with helping to speed passage of Social Security (Bennett, p. 177).

William Lemke and Dr. Francis Townsend, Washington, D.C., 1939. Library of Congress.

Townsend and his supporters were scornful of economists who found the plan unworkable, assailing the “brain trust professors . . . who don’t care a tinker’s damn how the old folks live or die.” Townsend himself proclaimed on more than one occasion, “God deliver us from the professional economists.” The plan, of course, was unworkable. An economist’s nightmare, the yearly costs were estimated at one and one-half times the amount spent on government at all levels—federal, state, and local. And that did not take into account the huge inflationary (and highly regressive) cost of the transaction tax, the tremendous bureaucracy required to administer the program, and the fact that the 2% fee would be likely to drive low-profit-margin businesses—such as the securities exchanges—out of the country. It was derided as “believing in Santa Claus all over again.” But Townsend’s followers were zealously committed. Some boycotted merchants who would not extend them credit based on the certainty of income to come after the plan’s passage (Bennett, pp. 160, 155).

Congressional Democrats, worried that Townsend was becoming another demagogue, opened hostile hearings on his program in May 1936. Embarrassed by his lack of knowledge of economics, and under fire for the financial management of his organization, Townsend stormed out of the hearings, and the following month joined Smith and Coughlin in their plans for the Union Party.

William Lemke

William H. Lemke on the campaign trail, 1936.

Congressman William H. Lemke, the standard bearer for the Union Party, was the only elected official among the party leaders. Elected to Congress in 1932 as a Republican from North Dakota, he had the strong support of the Non-Partisan League—an agrarian reform organization that opposed the monopolistic practices of the railroads, financiers, and grain elevator operators in the northern Plains. The eldest son of a German-American farm family that had settled in the rugged Dakotas in 1883, by the time Lemke was of age his family was prosperous enough that he could attend the University of North Dakota, Georgetown, and ultimately Yale Law School. He became a lawyer, worked for farmers and farm organizations, and became active with the Non-Partisan League.

Lemke supported FDR in 1932 and campaigned avidly for him while also seeking his own congressional seat. He had met with Roosevelt early in 1932 and secured what he believed was a pledge on farm policy that involved stimulating inflation and guaranteeing high prices by “dumping” farm surpluses abroad; Lemke also expected to be a close advisor to the president on farm policy. A staunch supporter of the New Deal at first, when Roosevelt changed his ideas on farm relief to crop reductions coupled with parity payments to the farmers (policies advocated by Brain Truster Rexford Guy Tugwell and Agriculture Secretary Henry A. Wallace), Lemke felt betrayed. He denounced the Agricultural Adjustment Administration and the “brainless trust” as a farce and by 1935 was calling the New Deal a “new shuffle with the cards stacked.” Bravado and anti-(East Coast) intellectualism peppered his rhetoric. “Roosevelt will have to get rid of the ‘brain trust’ or he will be in fact as well as in the newspapers a real Kerensky and not a leader of men.” He railed against “Wall Street racketeers” and “international bankers” and the failure to pass inflationary measures such as the Bonus Army Bill, the remonetization of silver, and the issuance of greenbacks. He denounced the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation as an effort to prop up failed private banks, instead of establishing a central bank (Bennett, p. 95).

But Lemke’s real focus was on farm legislation. With his Senate colleague (and old friend) Lynn J. Frazier of North Dakota, he co-sponsored a series of farm bills designed to provide mortgage relief to farmers facing foreclosure. When the first of these was declared unconstitutional, he refashioned it and moved on to craft an even more sweeping program: the Frazier–Lemke Farm Refinance bill, which provided for the Farm Credit Administration to supply the cash necessary for farmers to pay off their mortgages or buy back their farms. In return, the government would offer new very low-interest mortgages, which would be issued as a bond issue. If the low interest rate precluded bond sales, the Federal Reserve would be ordered to issue $3 billion of “printing press” money for the farmers. Lemke became an agrarian hero.

Roosevelt opposed, but did not veto, the first two measures. Not only FDR, but most of official Washington, opposed the third measure. But to Lemke it was the solution, the panacea, to relieve not only the farmers, but also the entire economy—by putting new money in circulation to stimulate business. Roosevelt sought to have the bill killed, believing it would unbalance the entire economy. Lemke worked tirelessly to counter the administration’s effort to tie the bill up in committee and miraculously secured 218 signatures on a petition that defied the president and brought the vote to the floor. The administration counter-attacked and the final straw came when the Speaker of the House read a letter from William Green—president of the American Federation of Labor—claiming that “labor would suffer” because the bill would lead to a “reduction in living standards, reduced buying power and a more acute unemployment problem” (Bennett, p. 100). In the end 58 of the members who had signed the petition did not vote for the bill and the measure lost 235–142. Lemke was crushed and was ready to join with Roosevelt’s fiercest enemies in the ill-fated campaign of the Union Party.

The Union Party Challenge

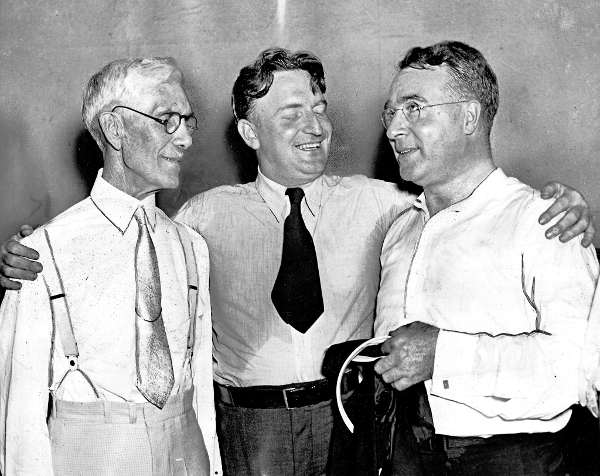

Dr. Francis Townsend, Gerald L. K. Smith, and Father Charles Coughlin after delivering speeches at Townsend Plan convention, Cleveland, July, 1936. United Press International.

They lost, of course. The 1936 election was a landslide for FDR. Despite their name, the four demagogues of the Union Party were hardly united and the campaign was plagued by all the problems you might expect when four megalomaniacs pledge cooperation. Too late to get Lemke on the ballot in crucial states, with little organization, short of funds, and plagued by internal squabbles, Lemke garnered only 892,378 votes—less than 2% of the popular vote. Roosevelt won 60.8% of the popular vote and 523 electoral votes to the Republican challenger Alfred Landon’s 8—the most lopsided electoral victory in American presidential history.

Lemke remained in Congress and continued to advocate for farmers until his death in 1950, but his reputation as a courageous agrarian reformer was tarnished by his association with the anti-Semitic far-right fringe of the Union Party.

******

But is this the end of the story? Lemke, Townsend, Coughlin, and Long/Smith posed a real challenge to the major parties. At their height they may have had as many as thirteen million followers, perhaps 10% of the population. As the Union Party they presented a formidable coalition of northeastern and Midwestern Roman Catholic urban voters, poor white southern cotton farmers, and financially strapped German and Scandinavian wheat farmers on the northern Plains, combined with a national movement of angry (formerly middle-class) white Protestant senior citizens. It was an unlikely mixture—riven by sectional, class, labor-agrarian, and religious differences—but still a potentially powerful voting bloc that the Democratic Party took very seriously.

What damage could have been done? An economy wrecked under the burden of the unsupportable payments to pensioners or farmers? Would confiscatory tax schemes and inflationary fiscal policies have killed American capitalism? Or would we have moved directly to Coughlin’s strange mixture of fascism and a centralized economy, taking with it his paranoid anti-Semitism? All of this and more was in the air. Earl Browder (Communist), Norman Thomas (Socialist), and John W. Aiken (Socialist Labor) were also on the ticket that year. And the Silver Shirts and other fascists were waiting in the wings. But all of these voices were in the “fringe” and none was able to capture the nomination of a major party. That would have to wait until 2016.

By today’s standards the voices of dissent in the 1930s were muffled: radio was new and powerful and everyone, Roosevelt included, used it to great benefit. But newspapers, the U.S. mail, telegrams, in-house print publications, even the polls and political science of the 1930s, were slow and imprecise tools compared with the power of today’s 24-hour news cycle, Internet newsfeeds, sophisticated polling and statistical models, and social media.

Many of today’s political leaders, like the radio priest and Dr. Townsend, trade on their celebrity and authority as anti-establishment “outsiders” to secure political power. This has a dangerous appeal. Coughlin was only stopped by his Canadian birth. Huey Long was cut down by an assassin. Truth and sound economics could not stop Dr. Townsend’s believers.

If demagoguery is an enduring part of democracy, can we take comfort in the fact that it has always been with us but has not prevailed—at least not in this country? But what if the conditions of 1936 had been different? What if Coughlin, Townsend, Smith, and Lemke had better party discipline or the power of modern communications?

The populace enthralled to demagogues has not changed. Their willingness to believe in easy solutions to intractable problems is still with us. People still relish the tough talk, name calling, and scapegoating. They love to be entertained by the bombast, to hear the demagogue shout the things no “gentleman” would say. Most of all, people today are just as willing as they always have been to follow a charismatic leader who promises to solve their problems and deliver the American dream.

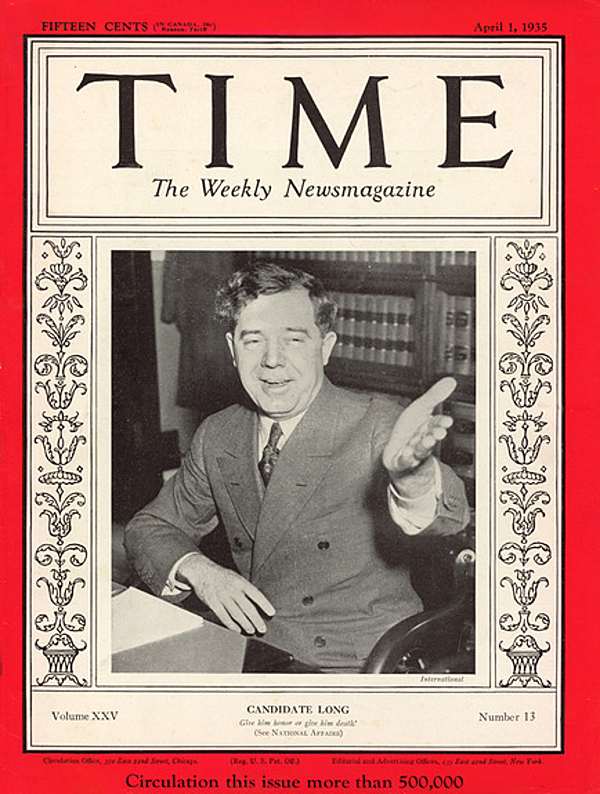

Huey Long on the cover of Time magazine, April 1, 1935.

But can people be blamed for seeking the American dream? Alan Brinkley in Voices of Protest makes the point that Long’s Share Our Wealth Plan could not be easily dismissed as sheer demagoguery. Yes, it was simple and “seriously, perhaps fatally, flawed.” But by other measures of demagoguery it fell short. “It was not an attempt to divert attention away from real problems; it did not focus resentment on irrelevant scapegoats or phony villains. It pointed, instead, to an issue of genuine importance; for the concentration of wealth was . . . a fundamental dilemma of the American economy” (p. 74). And, of course, it still is.

The panaceas of the demagogues of 1930s spoke to the essential economic inequality and exploited xenophobia, both of which still plague us today. Fortunately, in the 1930s Franklin Roosevelt was able to counter their worst invective and most outlandish schemes with a message that reinvigorated the democratic process and envisioned an American Dream of inclusivity as well as prosperity. Not self-centered, it demanded common effort toward shared goals for a better future.

“It is your problem, my friend, your problem no less than it is mine. Together we cannot fail, ” he said in his First Fireside Chat, March 12, 1933. This message of joint effort and joint responsibility leading to a bright future was a message he delivered throughout his long presidency. He was never more eloquent than in this, the final speech of the 1940 campaign.

I see an America where factory workers are not discarded after they reach their prime, where there is no endless chain of poverty from generation to generation, where impoverished farmers and farm hands do not become homeless wanderers, where monopoly does not make youth a beggar for a job.

I see an America whose rivers and valleys and lakes—hills and streams and plains—the mountains over our land and nature‘s wealth deep under the earth—are protected as the rightful heritage of all the people.

I see an America where small business really has a chance to flourish and grow.

I see an America of great cultural and educational opportunity for all its people.

I see an America where the income from the land shall be implemented and protected by a Government determined to guarantee to those who hoe it a fair share in the national income. . . .

I see an America with peace in the ranks of labor. . . .

I see an America devoted to our freedom—unified by tolerance and by religious faith—a people consecrated to peace, a people confident in strength because their body and their spirit are secure and unafraid.

(Franklin D. Roosevelt, Cleveland, November 2, 1940)

And Roosevelt codified the dream in the Economic Bill of Rights that he included in his Annual Message to Congress on January 11, 1944, making explicit a concrete connection between individual freedom and economic security. To Roosevelt economic security was a second Bill of Rights “under which a new basis of . . . prosperity can be established for all regardless of station, race, or creed.”

Roosevelt’s record of accomplishment effectively silenced the demagogues and created a template for liberal democracy that endured for forty years. It is important that we look back to this perilous era in American history because liberal democracy is not complete and its unfinished business is the truth behind today’s demagoguery.

To counter the demagogue, our leaders must take seriously the Black Lives Matter movement as well as the white middle- and working-class calls for protection from joblessness. Income inequality is as much a threat to our democracy as it was in the 1930s. And the xenophobic fears that would shut our doors to immigration pose threats to individual liberty. As FDR warned in his Economic Bill of Rights speech, “Necessitous men are not free men. People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.” Today’s problems are echoes of the unfinished business of the Roosevelt era. Today’s democratic leaders must challenge those who use demagoguery to offer unworkable and simplistic solutions to our truly pressing problems.

Roosevelt did not hesitate to use the power of his office—both as inspirational leader and in the exercise of raw political power—but most importantly, by his policies he gave the lie to those who claimed he was deaf to the needs of ordinary Americans. People could honestly answer with a resounding “Yes” the question of whether they were better off in 1936 or 1940 or 1944 than they were in 1933.

Yes, it is harder today. The issues are not so starkly drawn and today’s political climate encourages demagoguery in ways unknown in Roosevelt’s time. The old allegiances that channeled many voters are weaker now. Labor unions, party loyalty, religious affiliation, race and ethnicity, and even political machines once helped voters choose candidates that represented their interests. Instead, today sophisticated political campaigns with their legions of spokespersons and the ever-growing ranks of the punditry spin political discourse for months, even years. More often than not the debate devolves to character assassination and bogus scapegoating with the media and campaign surrogates offering a succession of excuses, explanations, and scorecards on truthfulness instead of discussion of relative policy positions.

In this political climate, people must decide for themselves amid a welter of nonstop political banter, which is an unhappy by-product of our twenty-first century revolution in mass communications. The result is often more stultifying and stupefying than energizing for those who participate in democracy.

These realities make the ability to distinguish between candor and cant more difficult than ever. Individual judgment is more important than ever. Instead a bored, fragmented, polarized, and poorly educated electorate relies on newsfeeds and media that as often as not report what the voter already believes or wants to hear. More than was ever possible in the 1930s, today’s demagogue is empowered to tell the most gullible among us exactly what we want to hear. And as Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt warned, we are in danger of losing our liberties along the way.

******

Sources

Bennett, David H. Demagogues in the Depression: American Radicals and the Union Party, 1932–1936. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1969. I am indebted to this work for much of the historical narrative in this article.

Brinkley, Alan. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Churchill, Winston. “Soapbox Messiahs.” Collier’s, June 20, 1936.

Kennedy, David M. Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Luthin, Reinhard H. “Some Demagogues in American History.” American Historical Review 57 (1951): 22–46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1849476