“There has perhaps never been a time when it was more important for us in the United States to understand the background, history, and present state of the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking peoples to the south of us.”

-Richard Pattee, Assistant Chief in the Division of Cultural Relations at the U.S. Department of State, statement in the preface to Along the Inca Highway, published in 1941

In his first inaugural address, President Roosevelt extended his hand in friendship to our southern neighbors in Mexico and South America when he announced his Good Neighbor Policy. As Breeann Robertson writes in “Textbook Diplomacy, The New World Neighbors series and Inter-American Education during World War II” writes in her dissertation thesis, “in early 1941, the United States was a nation on the brink of war. For strategic planners and political leaders in the United States, Latin American nations appeared particularly vulnerable to Axis invasion by Germany, Italy and Japan. According to Fortune magazine, by August 1941 only a small fraction of the American public—fewer than 7 percent—believed that Hitler had no political designs on either North or South America. More than 72 percent, by contrast, were convinced that “Hitler won’t be satisfied until he has tried to conquer everything including the Americas.”

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor created an immediate need to re-set the U.S. relationship with Latin America. FDR’s first inaugural laid the groundwork:

“In the field of World policy, I would dedicate this nation to the policy of the good neighbor, the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others, the neighbor who respects his obligations and respects the sanctity of his agreements in and with a World of neighbors.”

In order to create a friendly relationship between the United States and Central as well as South American countries, Roosevelt’s policy reversed previous interventionist perspectives. Cordell Hull, FDR’s Secretary of State, made the case in Montevideo at a conference of American states in December 1933: “No country has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.” Roosevelt then confirmed the policy in December of the same year: “The definite policy of the United States from now on is one opposed to armed intervention.”

The Good Neighbor Policy terminated US occupation of Nicaragua and Hait in the 1930s, re-calibrated our relationship with Cuba in 1934 by terminating the Platt Amendment, and negotiated compensation for Mexico’s nationalization of foreign-owned oil assets in 1938. These are some of the diplomatic maneuvers – but President Roosevelt and his team also knew that, in addition to basic state-craft, they needed to reach the hearts and minds of ordinary Americans and invite them to re-imagine negative stereotypes of Latin Americans which painted Latinos as lazy, suspicious and uncivilized. So they set about their task using the tried and true tools of imagineering – arts and leisure. In the leisure industry, the United States Maritime Commission contracted with Moore-McCormack Lines to operate a “Good Neighbor” fleet of ten cargo ships and three ocean liners between the United States and South America. The passenger liners SS California, Virginia and Pennsylvania were refurbished and renamed them SS Uruguay, Brazil and Argentina for their new route between New York and Buenos Aires via Rio de Janeiro, Santos and Montevideo.

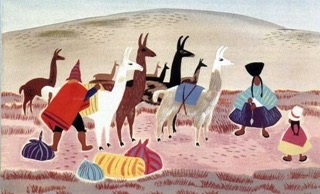

Roosevelt also created the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA) in August 1940 and appointed Nelson Rockefeller to head the organization. The sister division to the OCIAA, the Motion Picture Division, was headed by John Hay Whitney, with the main intent to abolish preexisting stereotypes of Latin Americans that were prevalent throughout American society. Whitney was convinced that “power of Hollywood films could exert in the two pronged campaign to win the hearts and minds of Latin Americans and to convince Americans of the benefits of Pan American friendship.” Whitney encouraged film studios to hire Latin Americans and to produce movies that placed Latin America in a favorable light. Further, he urged filmmakers to refrain from producing movies that perpetuated negative stereotypes. The government underwrote Walt Disney’s research trip to Mexico and South America in 1941, which resulted in the production of three animated features and later, the design and conceptual art for live attractions at Epcot Center created by the American animator and illustrator Mary Blair, who was part of the Disney group that traveled to South America.

The Office of War Administration also used striking visual illustrations to deliver impact to FDR’s policy goal. The most notable is Leon Helguera’s poster illustration entitled “Americans All.” Born in Mexico, Mr. Helguera worked as an illustrator and cartoonist for several Mexican publications before coming to the United States. In 1943, his design tor a stamp honoring the United Nations was chosen by the United States Post Office Department in a contest among leading American artists. He also designed stamps for the United States and the United Nations.

Please join us as we celebrate and study the legacy of the Good Neighbor Policy, with programming throughout 2017 beginning with our inaugural gala event. For information, please contact marcela.davison.aviles [at] fdrfoundation.org. And please support the program by donating here.