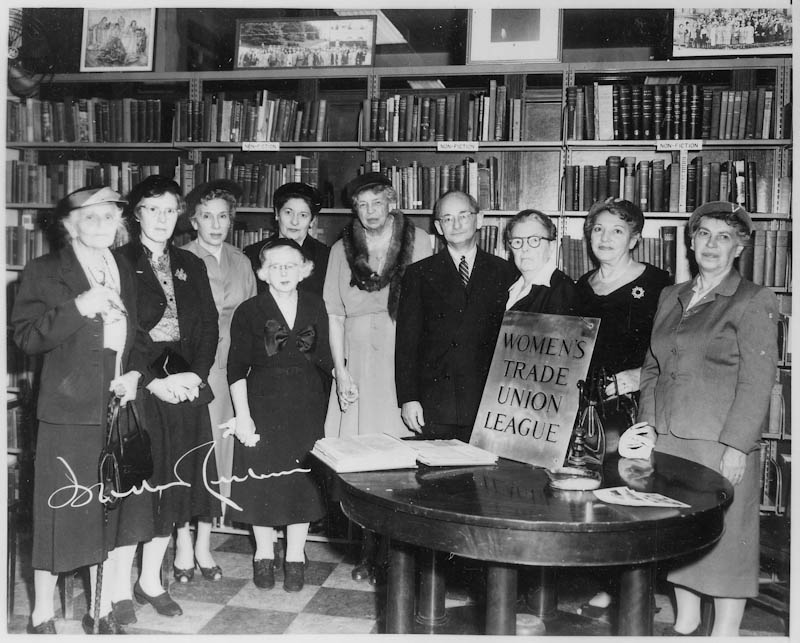

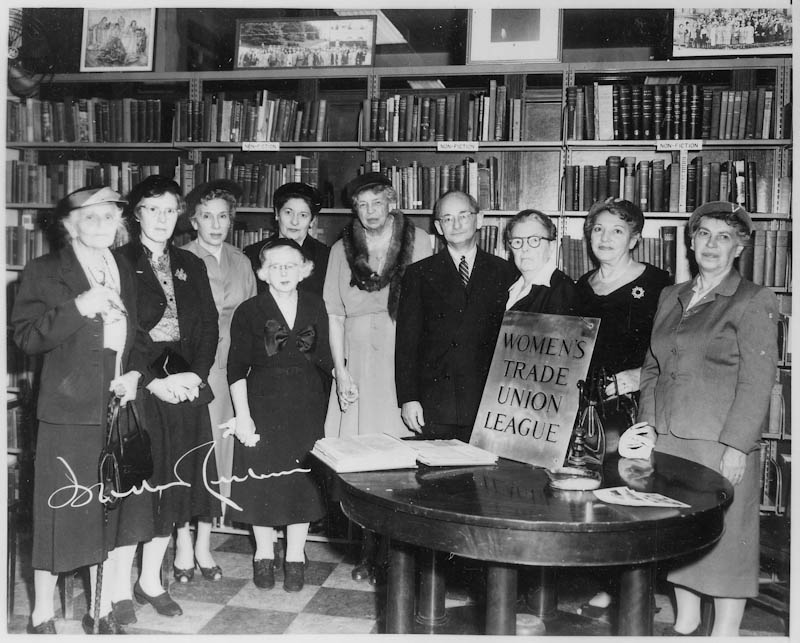

“A Woman is Like a Tea Bag”: Eleanor Roosevelt, and Radical Women of the 20s and 30s 3-26

Eleanor Roosevelt liked to say, “A woman is like a tea bag. You never know how strong it is until it’s in hot water.” In many ways Eleanor Roosevelt would have seemed the unlikeliest of feminists: a woman with five children married to man of traditional values. But early on, she became part of a circle of women leaders in the 20s and 30s who worked for labor legislation, world peace, women’s representation the Democratic Party, civil rights, equal pay and education for women, public housing — and the rest is history. This discussion shines a light on Eleanor Roosevelt and some of the women who were her friends and colleagues in the fight for social justice.

About the speaker: CYNTHIA M. KOCH is Historian in Residence and Director of History Programing for the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation at Adams House, Harvard University. She was Director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York and subsequently Senior Adviser to the Office of Presidential Libraries, National Archives, Washington, D.C. From 2013-16 she was Public Historian in Residence at Bard College, where she taught courses in public history and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. Her most recent publications are “They Hated Eleanor, Too,” “Hillary R[oosevelt] Clinton,” “Demagogues and Democracy,” and “Democracy and the Election” are published online by the FDR Foundation http://fdrfoundation.org/.

About the speaker: CYNTHIA M. KOCH is Historian in Residence and Director of History Programing for the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation at Adams House, Harvard University. She was Director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York and subsequently Senior Adviser to the Office of Presidential Libraries, National Archives, Washington, D.C. From 2013-16 she was Public Historian in Residence at Bard College, where she taught courses in public history and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. Her most recent publications are “They Hated Eleanor, Too,” “Hillary R[oosevelt] Clinton,” “Demagogues and Democracy,” and “Democracy and the Election” are published online by the FDR Foundation http://fdrfoundation.org/.

Previously Dr. Koch was Associate Director of the Penn National Commission on Society, Culture and Community, a national public policy research group at the University of Pennsylvania. She served as Executive Director (1993-1997) of the New Jersey Council for the Humanities, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and was Director (1979-1993) of the National Historic Landmark Old Barracks Museum in Trenton, New Jersey.

Join us beside a crackling fire in the FDR Suite 7 PM Monday 3/26

Sign up information HERE

Then and Now: When Presidents Fear

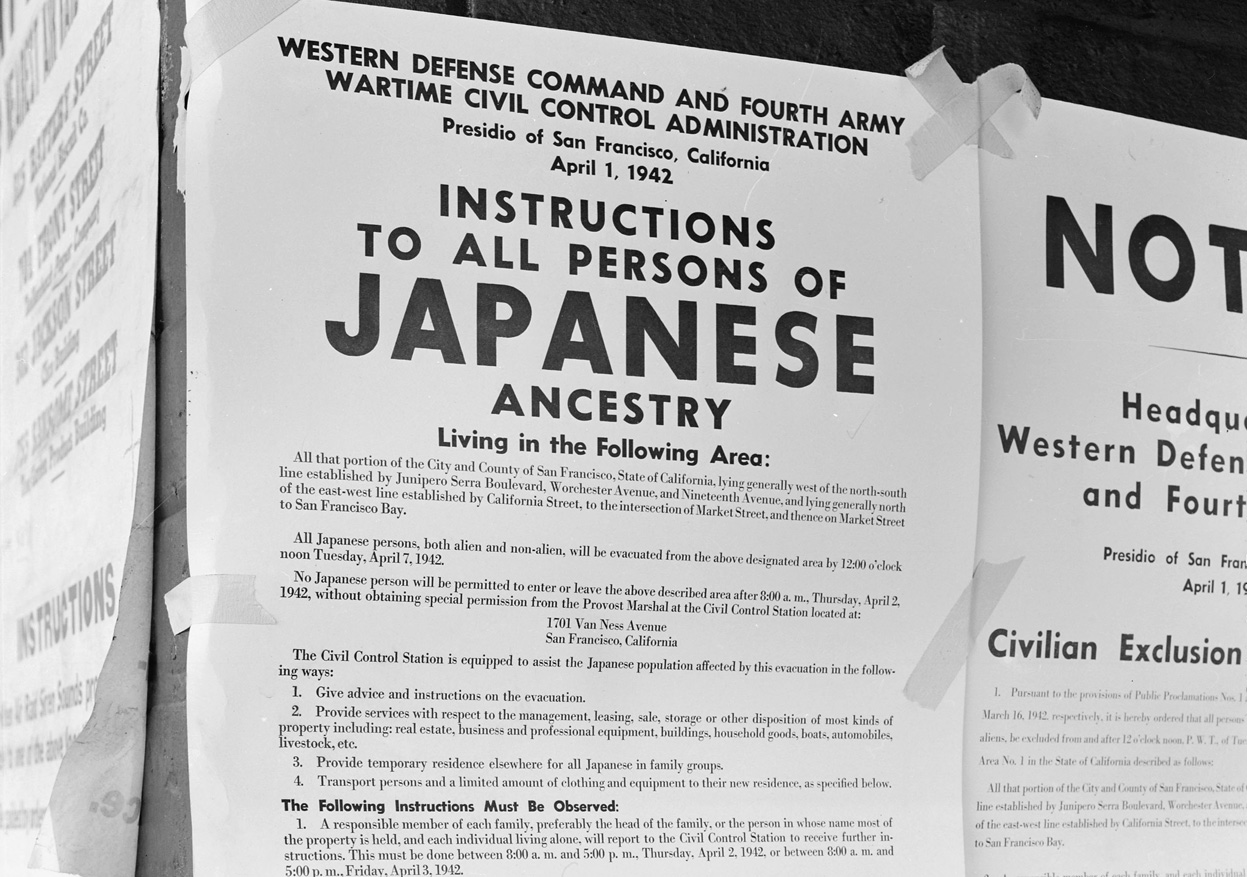

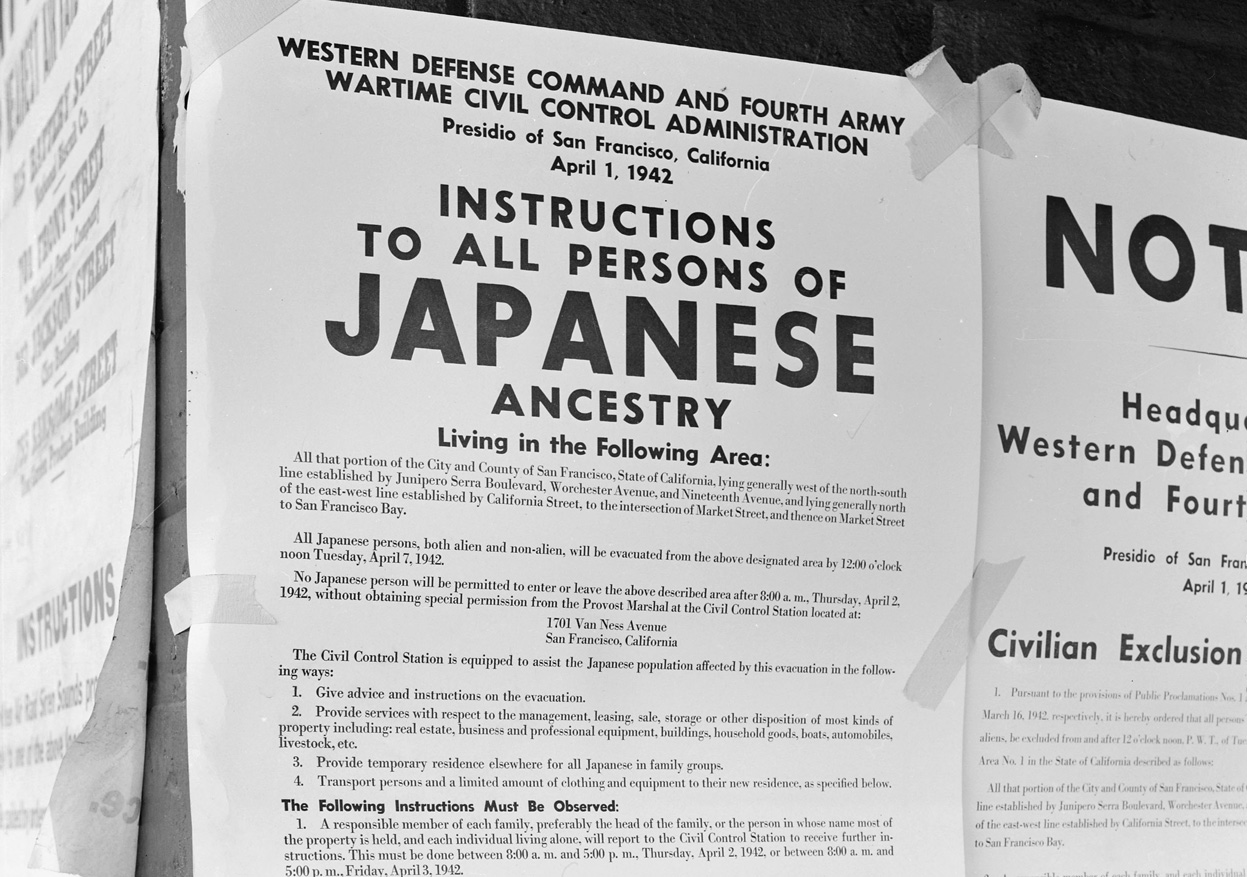

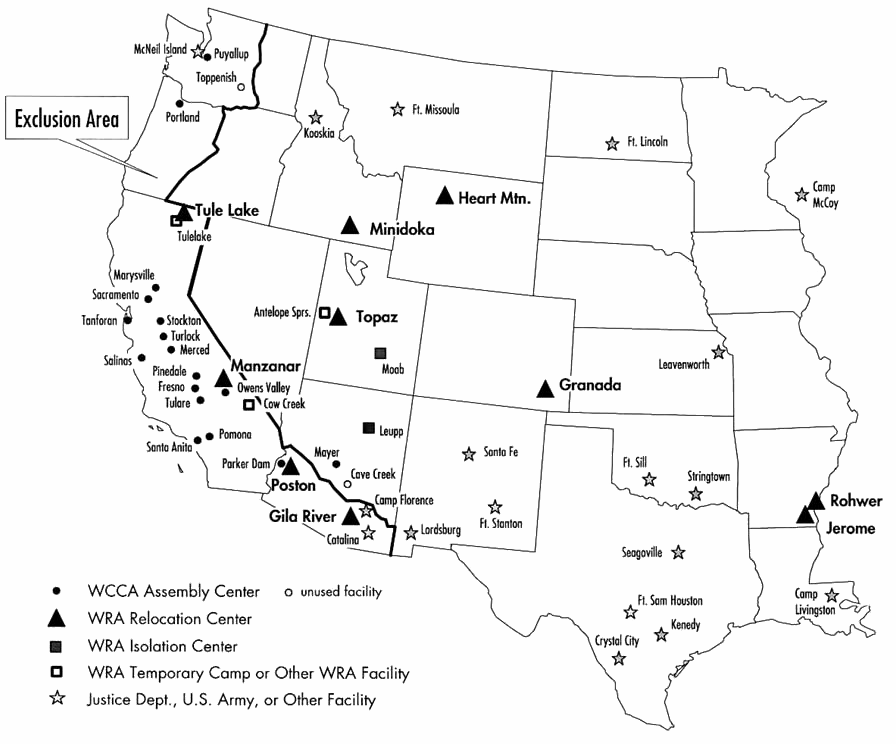

Franklin Roosevelt is remembered for “We have nothing to fear but fear itself,” the ringing words by which he inspired courage and hope in a nation devastated by the Great Depression. Eight years later, in the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, this same president signed Executive Order 9066, which removed over 110,000 Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast and confined them to internment camps during World War II.

If Franklin Roosevelt, champion of the Four Freedoms, fell prey to xenophobia in 1942, with lasting injury to our democracy, what damage is being done today by the Trump presidency, which targets Muslims, Mexicans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Africans.

Greg Robinson’s historical paper was originally presented at our conference When Presidents Fear on March 4, 2017. We post it now in remembrance of the 76th anniversary of Executive Order 9066.

FDR’s Decision to sign Executive Order 9066: Lessons From History

Greg Robinson, Professor of History at l’Université du Québec À Montréal.

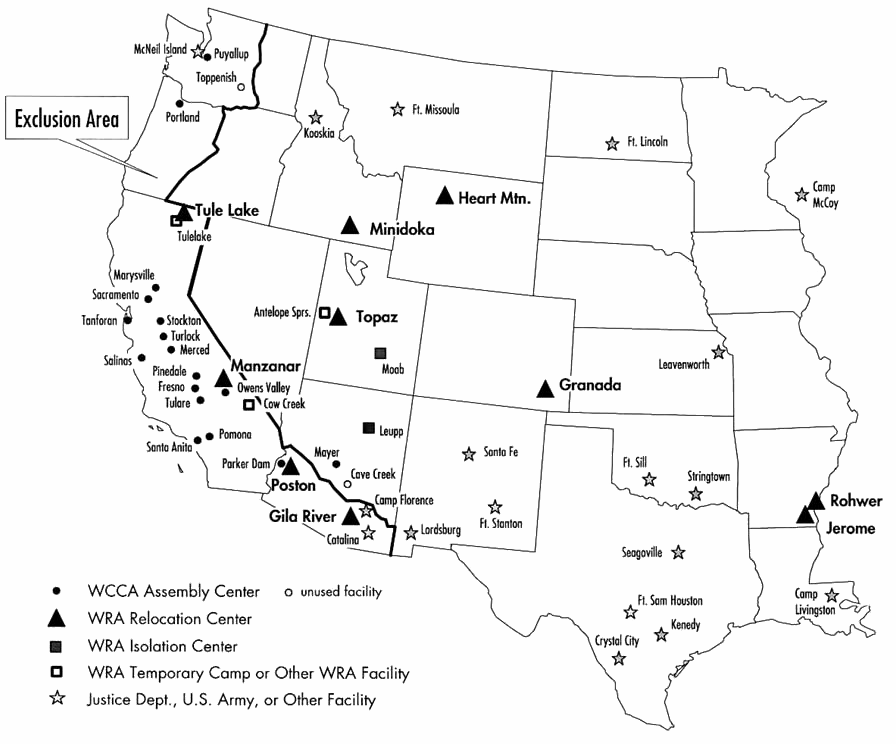

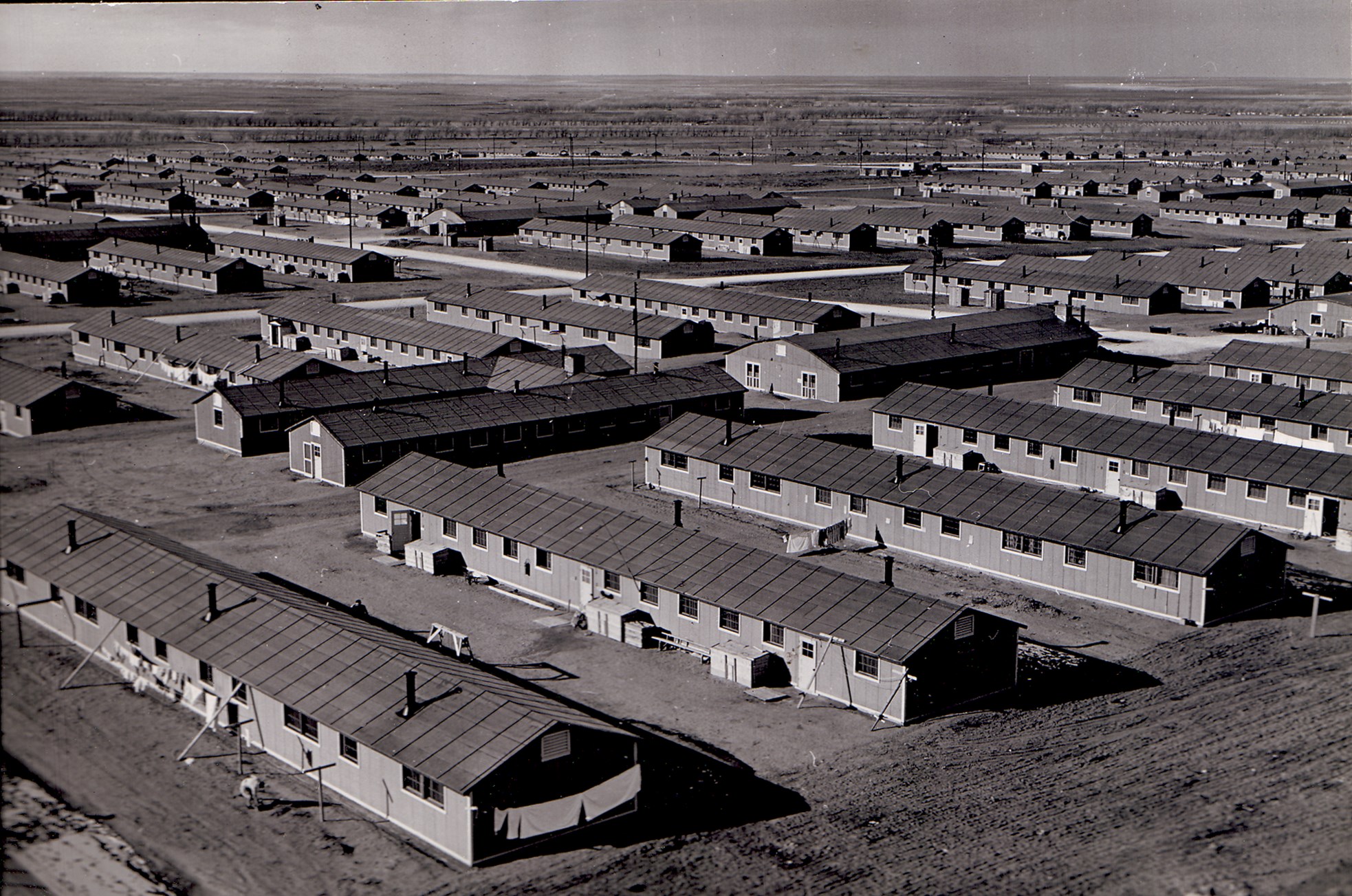

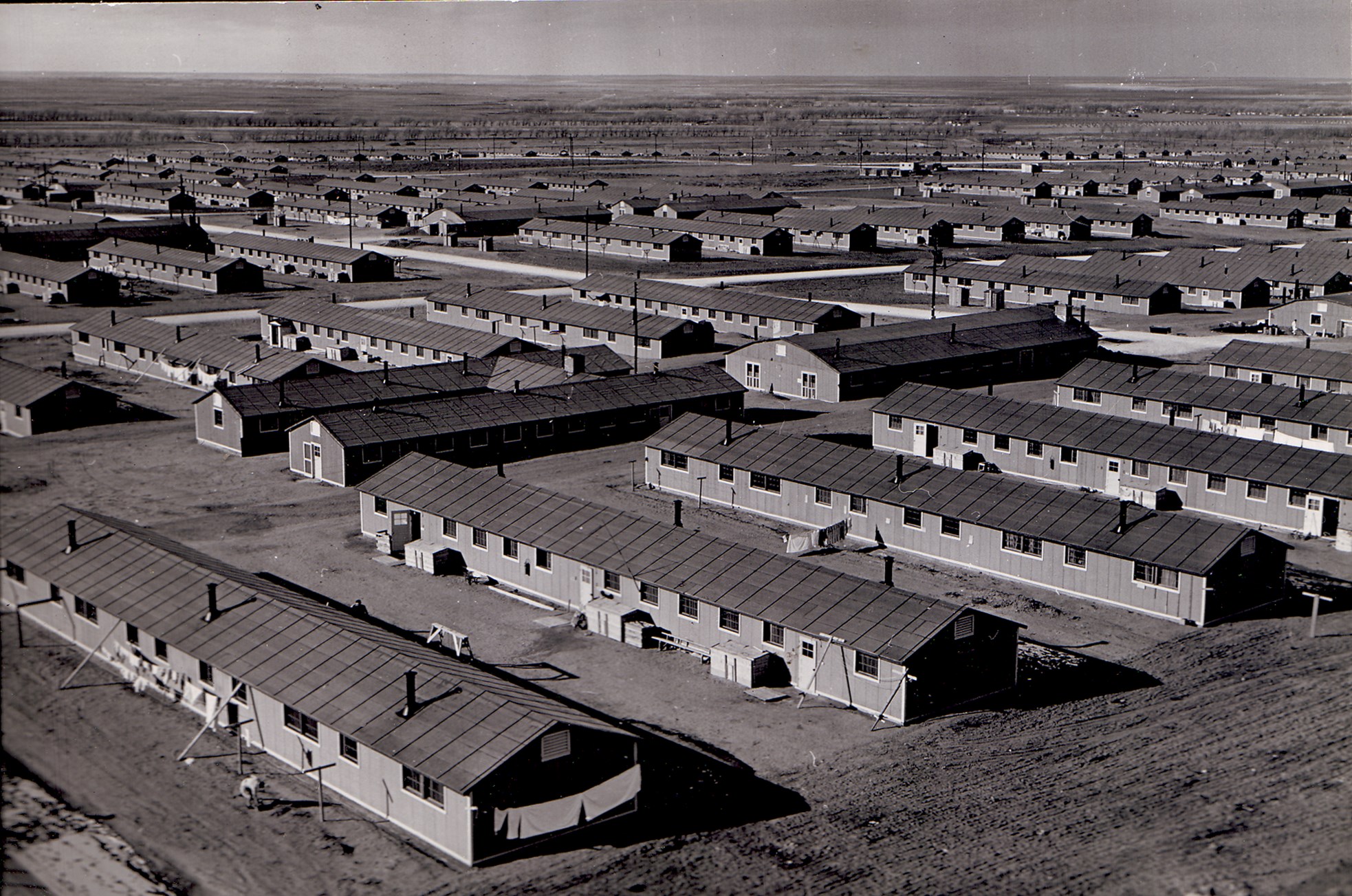

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D Roosevelt singed Executive Order 9066. As a result of the President’s order, over 110,000 Japanese Americans were ordered from their homes without trial and sent to camps under military guard. Some 70,000 of these people were U.S. citizens of an average age of approximately 18, and the rest were long-resident aliens who were predominantly middle-aged. They were allowed to take only what they could carry, and were thus forced to sell or dispose of homes, businesses, cars and all other personal property. The Japanese Americans were first herded into a network of “Assembly Centers,” which were generally disused fairgrounds and race tracks. There the inmates were housed in stables and animal pens. After several weeks or months, the Japanese Americans were sent on under guard to a network of “relocation centers,” camps operated by a new government agency, the War Relocation Authority. These American-style concentration camps were located in remote desert and swamp areas and were surrounded by barbed wire and armed sentries. The inmates were housed in hastily-built tar paper shacks, with one room per family. Health and sanitary facilities were primitive, especially at the outset, and food was limited and poor quality. Although all adults were expected to work, their maximum salary was set at $19 per month. The stark conditions of the camps and the stigma of arbitrary imprisonment led to trauma and conflict among the inmates, and sparked several strikes and riots in the camps. In the end, most Japanese Americans remained in the camps throughout the war years.

How could this have happened in a nation fighting a war to preserve freedom against fascism? In particular how could it have happened during the administration of Franklin Roosevelt, a President justly renowned for his humanitarianism and support for democracy? This is the question with which I began my inquiry. Still, it is possible to identify several important factors that shaped the President’s actions. As Milton Eisenhower, who became the first director of the WRA, the civilian government agency that ran the camps, later stated, “The President’s final decision was influenced by a variety of factors, by events over which he had little control, by inaccurate or incomplete information, by bad counsel, by strong political pressures, and by his own training, background and personality.”

In my book By Order of the President (Harvard University Press, 2001), I discuss at length how all these factors influenced the actions of President Roosevelt, first in his decision to approve the mass removal of West Coast Japanese Americans, and subsequently in his actions in support of the policy. Although sporadic, these decisions were essential in determining the duration of the incarceration and the consequences to its victims. What I would like to explore is to look at the role played in the President’s decision by the last of the factors cited by Eisenhower, namely the President’s training, background, and personality. From this point of view, the President’s past attitudes towards Japanese Americans must be considered as a significant factor in his decision to approve Executive Order 9066. Franklin Roosevelt had a long history of viewing Japanese Americans in undifferentiated racial terms as essentially Japanese, and of expressing hostility to them on that basis.

In order to understand this history, it is necessary to look back at the turn of the century American society in which the young Franklin Roosevelt grew up and came of age, and how he was shaped by dominant ideas. At the time, the nation’s intellectual climate was dominated by Darwinian or biological thinking. According to the ideas of Charles Darwin on animal evolution, which were adapted to human society by such thinkers as Herbert Spencer and William Graham Sumner, humanity was divided into different groups, or races. Just as the various species of animals adapted in order to survive more easily in a given environment, each race developed particular characteristics that gave them an advantage. Thus, the various races developed not only different physical characteristics—height, skin color, body shape, skull shape, and so forth—in response to their particular surroundings, but also particular personality traits.

How did these ideas affect the young FDR? He deplored visceral prejudice, and he expressed interest in Japanese culture and became friendly with a number of Japanese. Nevertheless, he regarded the Japanese as a danger. In 1913, shortly after Roosevelt was named Assistant Secretary of the Navy in the government of Woodrow Wilson, the protests of California whites against Japanese immigrant farmers led to the Alien Land Act, as I mentioned, which forbade these immigrants property rights. The passage of the law set off vigorous protests within Japan, and when an extreme nationalist called for a blockade of America in return, Roosevelt had drawn up a plan for naval war between Japan and the United States and recommended the massing of the Pacific fleet in preparation for such a war. Although the immediate crisis abated following some careful diplomacy, in the years that followed, even as the United States moved closer to involvement in World War I, he continued to call for the arming of the Pacific fleet for war against Japan, which he considered the most dangerous foreign threat. The greatest lesson he took from the incident was that Japanese Americans were a source of trouble—friction with their neighbors and aggression by Japan.

How did these ideas affect the young FDR? He deplored visceral prejudice, and he expressed interest in Japanese culture and became friendly with a number of Japanese. Nevertheless, he regarded the Japanese as a danger. In 1913, shortly after Roosevelt was named Assistant Secretary of the Navy in the government of Woodrow Wilson, the protests of California whites against Japanese immigrant farmers led to the Alien Land Act, as I mentioned, which forbade these immigrants property rights. The passage of the law set off vigorous protests within Japan, and when an extreme nationalist called for a blockade of America in return, Roosevelt had drawn up a plan for naval war between Japan and the United States and recommended the massing of the Pacific fleet in preparation for such a war. Although the immediate crisis abated following some careful diplomacy, in the years that followed, even as the United States moved closer to involvement in World War I, he continued to call for the arming of the Pacific fleet for war against Japan, which he considered the most dangerous foreign threat. The greatest lesson he took from the incident was that Japanese Americans were a source of trouble—friction with their neighbors and aggression by Japan.

Even when FDR’s attitude towards Japan began to change, following the end of the First World War, his opinions about Japanese Americans remained constant. In 1922-1923 FDR was invited by his old friend George Marvin to write an article for Asia magazine about Japanese-American relations. It was a time of international tension, following the Washington Naval Conference. Roosevelt feared that a resurgence of militarism would set off a futile and costly war between Japan and the United State, and he decided to write in opposition. By March 1923 he had produced the first draft of a text called “The Japs – A Habit of Mind.” After Marvin made some minor stylistic changes and inserted some additional factual material, the piece appeared under the title “Shall We Trust Japan?” in the July 1923 issue of Asia.

“Shall We Trust Japan?” was designed as a plea for a “pacific attitude” in the Pacific and for an end to the instinctive hostility most Americans felt for Japan. Roosevelt’s principal argument was that, even assuming that it had been “natural” in the past for Japan and the United States to consider each other as “the most probable enemy” and to plan for war against the other, the new era crystallized by the Washington Naval Conference made such thought obsolete. FDR expressed confidence that, once the “yellow peril” fears of Japan were eliminated, the two countries could resolve peacefully the underlying causes of Japanese American friction.

Roosevelt confessed that the principal cause of such friction, which had to be eliminated, was the presence of Japanese immigrants and their children in the United States. FDR brought up this vital question with reluctance, because, as he said, it was so difficult to discuss without sparking “unreasoning passions on one side or both.” Nevertheless, while he conceded that the Japanese, as well as other groups such as the Chinese, Filipinos, and Indians, were “ a race…of acknowledged dignity and integrity,” they nonetheless had to be excluded on racial grounds from the United States

So far as Americans are concerned, it must be admitted that, as a whole, they honestly believe—and in this belief they are at one with the people of Canada and Australasia—that the mingling of white with oriental blood on an extensive scale is harmful to our future citizenship…As a corollary of this conviction, Americans object to the holding of large amounts of real property, of land, by aliens or those descended from mixed marriages. Frankly, they do not want non-assimilable immigrants as citizens, nor do they desire any extensive proprietorship of land without citizenship.

The assertion that Americans (whom Roosevelt clearly assumed were white) “honestly” believed that they had to combat mixed marriages through discriminatory legislation and that people of “oriental blood” were inherently and ipso facto unassimilable, constituted an undeniable rationalization of white prejudice both towards Japanese immigrants and towards their native-born children in the United States. Roosevelt continued that immigration restriction, whether by laws or by the Gentleman’s Agreement, was morally justified because it was reciprocal :

The reverse of the position thus taken holds equally true. In other words, I do not believe that the Americans people now or in the future will insist on the right or privilege of entry into an oriental country to such an extent as to threaten racial purity or to jeopardize the land-owning privileges of citizenship. I think I may sincerely claim for American public opinion an adherence to the Golden Rule.

Even ignoring the fact that white Americans never in fact obeyed the “golden rule”—the United States held colonies in Asia and American investors enjoyed extensive property rights and extraterritoriality in Asia—Japan was not a nation of immigrants, and there never were any large groups of Americans who wished to emigrate there. Although Japan limited immigration, it never singled out Americans or whites for exclusion on a racial basis.

In any case, Roosevelt’s assertion that discriminatory laws had been passed in order to preserve “racial purity” was illogical. White-Asian intermarriage was statistically insignificant on the West Coast, where such laws existed, and in any case laws banning the practice had existed long before passage of the Alien Land Act, so it could not have been passed to prevent the threat of mass intermarriage. Instead, as Roosevelt well knew, such laws were passed to reduce economic competition Japanese immigrant farmers and landowners and to stigmatize them as undesirable.

Roosevelt nevertheless continued to believe that the Japanese would not object to race-based exclusion. In 1925, while on his first visit to the Georgia resort of Warm Springs, to take treatments for his wasted legs, he began a short-lived substitute newspaper column in the nearby Macon Telegraph. One of his columns, dated April 30, 1925, explored the “Japanese question.” It was written during a minor diplomatic crisis between the United States and Japan prompted by the announcement that the US Navy would be undertaking naval maneuvers in Hawaii designed to guard against an eventual Japanese attack. Roosevelt agreed that the Americans had a perfect right to defend their coasts, in which the Hawaiian bases played a vital role, but he deplored the announcement as needlessly provocative. FDR declared that the announcement paralleled the campaign by “troublemakers” on both sides of the Pacific that had led to the Japanese exclusion law. He contended that the United States, instead of using economic arguments, should instead justify its policy on racial grounds. He saw no contradiction between American-Japanese friendship, on the one hand, and the exclusion of Japanese immigrants as a racial danger:

It is undoubtedly true that in the past many thousands of Japanese have legally or otherwise got into the United States, settled here and raised children who become American citizens. Californians have properly objected on the sound basic ground that Japanese immigrants are not capable of assimilation into the American population. If this had throughout the discussion been made the sole ground for the American attitude all would have been well, and the people of Japan would today understand and accept our decision.

Roosevelt was sure that if the United States defended exclusion on a purely racial basis, the Japanese would not protest and relations between the two countries would remain harmonious. After all, he said, the Japanese were known to have strong taboos against interracial marriage, and would not want to have their national culture polluted by such inter-mixtures:

Roosevelt was sure that if the United States defended exclusion on a purely racial basis, the Japanese would not protest and relations between the two countries would remain harmonious. After all, he said, the Japanese were known to have strong taboos against interracial marriage, and would not want to have their national culture polluted by such inter-mixtures:

Anyone who has traveled in the Far East knows that the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results…The argument works both ways. I know a great many cultivated, highly educated, and delightful Japanese. They have all told me that they would feel the same repugnance and objection to have thousands of Americans settle in Japan and intermarry with the Japanese as I would feel in having large numbers of Japanese come over here and intermarry with the American population. In this question then of Japanese exclusion from the United States, it is necessary only to advance the true reason—the undesirability of mixing the blood of the two peoples.

These words and action point to Roosevelt’s continued acceptance, in the months after Pearl Harbor, of the idea that Japanese Americans, whether citizens or longtime residents, were essentially Japanese and unable to transform themselves into true Americans. Therefore, in a time of conflict between the United States and Japan, they could be presumed to be supportive of their Japanese brethren. This presumption was not absolute—Roosevelt could well imagine that there existed loyal Japanese Americans. But in the absence (and sometimes in the presence) of significant evidence testifying to their loyalty, the presumption remained and controlled Roosevelt’s actions in regard to the Japanese American community generally. Roosevelt’s ideas about the Japanese left him prepared—even overprepared—to believe the worst of Japanese, and to accept without challenge in the wake of Pearl Harbor the military’s false accusations regarding the disloyal activities of a Japanese American fifth column, even if he had solid proof to the contrary. He therefore gave the Army much too free a hand in dealing with West Coast Japanese Americans.

Roosevelt’s basic attitude towards Japanese Americans may have also shaped his response to the moral and constitutional questions involved in mass evacuation. FDR’s refusal to admit the discriminatory purpose behind race-based exclusion of Japanese immigrants during the 1920s and his contention that Californians rightly objected to the Japanese presence in their midst also serves as a model for his voluntary blindness to the essential role of racial hostility and economic jealousy in motivating calls for mass removal of Japanese Americans by Californians with a long history of nativist bias. Moreover, during his 1920s articles, Roosevelt defended the denial of property rights to Japanese immigrants as a way to ensure racial purity. This attitude could well have contributed to Roosevelt’s unwillingness to stake steps to protect the property of the evacuees such the appointment of a strong Alien Property Custodian, with the result that the interned Japanese Americans were forced to sell off their property at ridiculously low prices or were stripped of it by the white “friends” to whom they entrusted it, or were forced to place it in unguarded warehouses which were looted and vandalized.

Roosevelt’s basic attitude towards Japanese Americans may have also shaped his response to the moral and constitutional questions involved in mass evacuation. FDR’s refusal to admit the discriminatory purpose behind race-based exclusion of Japanese immigrants during the 1920s and his contention that Californians rightly objected to the Japanese presence in their midst also serves as a model for his voluntary blindness to the essential role of racial hostility and economic jealousy in motivating calls for mass removal of Japanese Americans by Californians with a long history of nativist bias. Moreover, during his 1920s articles, Roosevelt defended the denial of property rights to Japanese immigrants as a way to ensure racial purity. This attitude could well have contributed to Roosevelt’s unwillingness to stake steps to protect the property of the evacuees such the appointment of a strong Alien Property Custodian, with the result that the interned Japanese Americans were forced to sell off their property at ridiculously low prices or were stripped of it by the white “friends” to whom they entrusted it, or were forced to place it in unguarded warehouses which were looted and vandalized.

Perhaps the most important part that Roosevelt’s anti-Japanese prejudices played in shaping his decision to approve mass removal and his subsequent actions in support of the policy was in nourishing an indifference to the condition of the Japanese Americans involved. As extraordinary as it may seem, Roosevelt was ready to approve mass removal without hesitation precisely because the matter was unimportant to him. In the end, it is this indifference, which marks not only Roosevelt’s decision to sign Executive Order 9066, but his involvement in the policy that followed. In that sense, the sin that pervaded the President’s actions, if we can use such a loaded term, was not hostility but indifference.

GREG ROBINSON is Professor of History at l’Université du Québec À Montréal. A specialist in North American Ethnic Studies and U.S. Political History, he has written several notable books, including By Order of the President: (Harvard UP, 2001) which uncovers President Franklin Roosevelt’s central involvement in the wartime confinement of 120,000 Japanese Americans, and A Tragedy of Democracy: (Columbia UP, 2009), winner of the 2009 AAAS History book prize, which studies Japanese American and Japanese Canadian confinement in transnational context. His book After Camp: (UC Press, 2012), winner of the Caroline Bancroft History Prize, centers on post war resettlement. His most recent book is The Great Unknown: Japanese American Sketches (UP Colorado 2016) an alternative history of Japanese Americans through portraits of unusual figures.

About the speaker: CYNTHIA M. KOCH is Historian in Residence and Director of History Programing for the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation at Adams House, Harvard University. She was Director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York and subsequently Senior Adviser to the Office of Presidential Libraries, National Archives, Washington, D.C. From 2013-16 she was Public Historian in Residence at Bard College, where she taught courses in public history and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. Her most recent publications are “They Hated Eleanor, Too,” “Hillary R[oosevelt] Clinton,” “Demagogues and Democracy,” and “Democracy and the Election” are published online by the FDR Foundation http://fdrfoundation.org/.

About the speaker: CYNTHIA M. KOCH is Historian in Residence and Director of History Programing for the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation at Adams House, Harvard University. She was Director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York and subsequently Senior Adviser to the Office of Presidential Libraries, National Archives, Washington, D.C. From 2013-16 she was Public Historian in Residence at Bard College, where she taught courses in public history and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. Her most recent publications are “They Hated Eleanor, Too,” “Hillary R[oosevelt] Clinton,” “Demagogues and Democracy,” and “Democracy and the Election” are published online by the FDR Foundation http://fdrfoundation.org/.

How did these ideas affect the young FDR? He deplored visceral prejudice, and he expressed interest in Japanese culture and became friendly with a number of Japanese. Nevertheless, he regarded the Japanese as a danger. In 1913, shortly after Roosevelt was named Assistant Secretary of the Navy in the government of Woodrow Wilson, the protests of California whites against Japanese immigrant farmers led to the Alien Land Act, as I mentioned, which forbade these immigrants property rights. The passage of the law set off vigorous protests within Japan, and when an extreme nationalist called for a blockade of America in return, Roosevelt had drawn up a plan for naval war between Japan and the United States and recommended the massing of the Pacific fleet in preparation for such a war. Although the immediate crisis abated following some careful diplomacy, in the years that followed, even as the United States moved closer to involvement in World War I, he continued to call for the arming of the Pacific fleet for war against Japan, which he considered the most dangerous foreign threat. The greatest lesson he took from the incident was that Japanese Americans were a source of trouble—friction with their neighbors and aggression by Japan.

How did these ideas affect the young FDR? He deplored visceral prejudice, and he expressed interest in Japanese culture and became friendly with a number of Japanese. Nevertheless, he regarded the Japanese as a danger. In 1913, shortly after Roosevelt was named Assistant Secretary of the Navy in the government of Woodrow Wilson, the protests of California whites against Japanese immigrant farmers led to the Alien Land Act, as I mentioned, which forbade these immigrants property rights. The passage of the law set off vigorous protests within Japan, and when an extreme nationalist called for a blockade of America in return, Roosevelt had drawn up a plan for naval war between Japan and the United States and recommended the massing of the Pacific fleet in preparation for such a war. Although the immediate crisis abated following some careful diplomacy, in the years that followed, even as the United States moved closer to involvement in World War I, he continued to call for the arming of the Pacific fleet for war against Japan, which he considered the most dangerous foreign threat. The greatest lesson he took from the incident was that Japanese Americans were a source of trouble—friction with their neighbors and aggression by Japan. Roosevelt was sure that if the United States defended exclusion on a purely racial basis, the Japanese would not protest and relations between the two countries would remain harmonious. After all, he said, the Japanese were known to have strong taboos against interracial marriage, and would not want to have their national culture polluted by such inter-mixtures:

Roosevelt was sure that if the United States defended exclusion on a purely racial basis, the Japanese would not protest and relations between the two countries would remain harmonious. After all, he said, the Japanese were known to have strong taboos against interracial marriage, and would not want to have their national culture polluted by such inter-mixtures: Roosevelt’s basic attitude towards Japanese Americans may have also shaped his response to the moral and constitutional questions involved in mass evacuation. FDR’s refusal to admit the discriminatory purpose behind race-based exclusion of Japanese immigrants during the 1920s and his contention that Californians rightly objected to the Japanese presence in their midst also serves as a model for his voluntary blindness to the essential role of racial hostility and economic jealousy in motivating calls for mass removal of Japanese Americans by Californians with a long history of nativist bias. Moreover, during his 1920s articles, Roosevelt defended the denial of property rights to Japanese immigrants as a way to ensure racial purity. This attitude could well have contributed to Roosevelt’s unwillingness to stake steps to protect the property of the evacuees such the appointment of a strong Alien Property Custodian, with the result that the interned Japanese Americans were forced to sell off their property at ridiculously low prices or were stripped of it by the white “friends” to whom they entrusted it, or were forced to place it in unguarded warehouses which were looted and vandalized.

Roosevelt’s basic attitude towards Japanese Americans may have also shaped his response to the moral and constitutional questions involved in mass evacuation. FDR’s refusal to admit the discriminatory purpose behind race-based exclusion of Japanese immigrants during the 1920s and his contention that Californians rightly objected to the Japanese presence in their midst also serves as a model for his voluntary blindness to the essential role of racial hostility and economic jealousy in motivating calls for mass removal of Japanese Americans by Californians with a long history of nativist bias. Moreover, during his 1920s articles, Roosevelt defended the denial of property rights to Japanese immigrants as a way to ensure racial purity. This attitude could well have contributed to Roosevelt’s unwillingness to stake steps to protect the property of the evacuees such the appointment of a strong Alien Property Custodian, with the result that the interned Japanese Americans were forced to sell off their property at ridiculously low prices or were stripped of it by the white “friends” to whom they entrusted it, or were forced to place it in unguarded warehouses which were looted and vandalized.