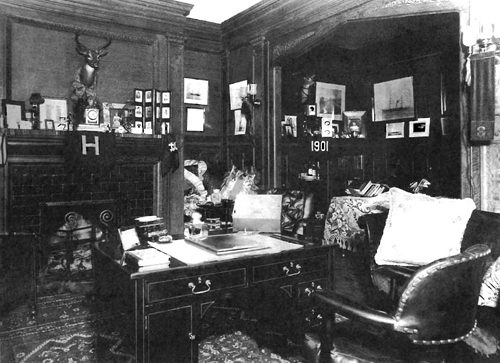

I can never forget what it felt like to come back to Harvard and Adams House in June of 1983 after nearly a year in the People’s Republic of China where Jana taught European history and French and I taught American literature at Sichuan University in Chengdu. When China reopened its borders to Americans, a small group of visiting professors came to Harvard in 1981. One of them audited my course on the novel, became a friend, and during lunch at Adams House (where everything interesting seems to happen), he invited me to come teach at his university. Knowing that it was a peculiar way for a professor of English to spend a sabbatical, I nonetheless felt a deep curiosity and determination to go. Three of our four children—Maria ‘99 (5), Christina ’91 (13), and Jan, Yale ’88 (17) –went to Chinese schools where American children had never been seen before. After nine years in Apthorp House, we found ourselves in the foreign faculty guest housing on campus—a cold-water two bedroom flat with no phone, no heat, three chairs, two beds, and a table. My Chinese students in a graduate seminar and a lecture course on the novel lived ten in a room in unheated dorms with no indoor toilets. The university library was closed to students. Most foreign books had been destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. I had cases of books sent from the COOP which I gave to my students. Dating was forbidden. (When our oldest daughter Anne, Conn. College ‘86 (19), came for a visit, she stayed a few nights in the women’s dorm and heard what a young Chinese woman’s life was like.) There were no extra-curricular activities other than sports. Gatherings of more than ten—except for political, academic or athletic purposes—were not permitted. When we and the other American teachers gave a Halloween party with a spook house, apple dunking, and square dancing, the word spread through an unofficial grape vine. First our own students flocked in and then truck loads of students appeared from other universities until the police appeared and chased them away.

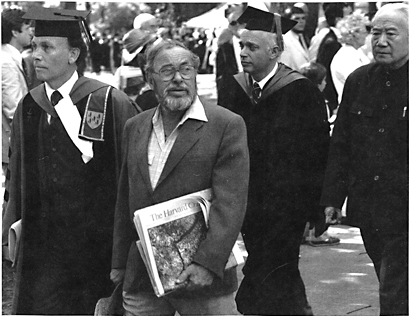

Some people have wondered why the Kielys stayed on so long at Adams House. 26 years! There are many reasons. China is one of them. As Jana and I sat at the diploma ceremony as guests of Acting Masters Richard and Joanne Kronauer, (I was still in my Mao jacket), I looked out with wonder at Randolph Court filled with well-dressed parents and friends, and around me at the prosperous and happy Adamsians in their black robes. (My Chinese students had no Commencement ceremony or job interviews. They found their next assignment posted on a bulletin board when classes were over.) Despite Spartan conditions and other limitations, our time in China was fantastic. With no modern technology and absolutely no travel experience, my students had excellent English; they treated books like treasures and proved to be astute and sensitive readers. Every weekend they and our Chinese colleagues took us on expeditions to mountain shrines, temples, communes, and hiking in areas of great natural beauty. They had little in the way of material possessions, but they welcomed us with extraordinary warmth and generosity. Having grown up in a time when China was regarded in this country with a combination of fear and ignorance, I was determined to make Adams House—as it had been for gay students, actors, artists, poets, and politicians—an exception.

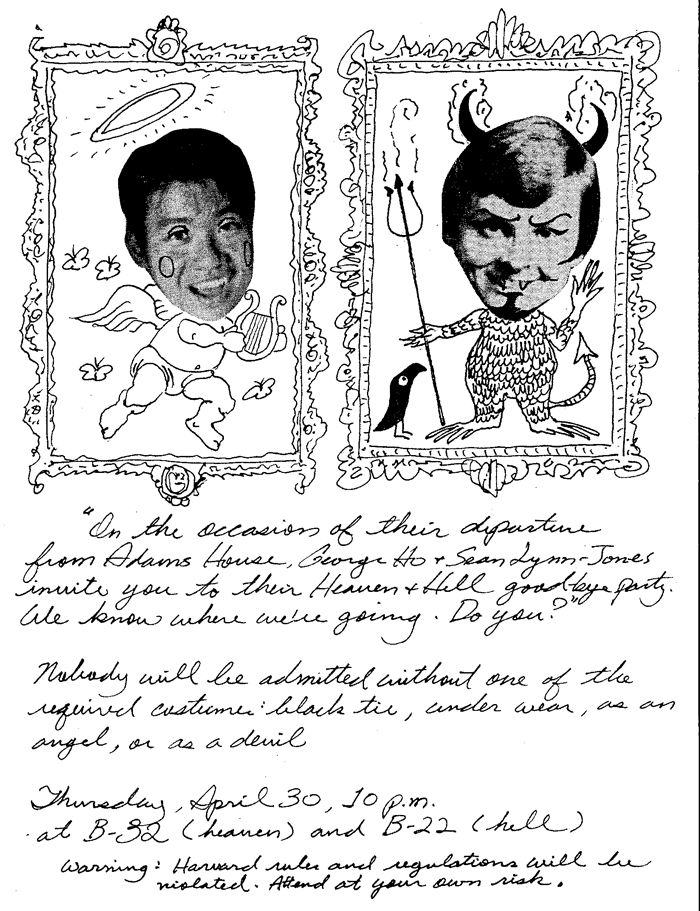

Jana and Bob Kiely with Han Xu, Chinese Ambassador to the United States, and his wife who painted the calligraphy as a presentation piece, 1985

Of course, I realized that Adams House was a small place to start. But I also knew that it was a good place to start and that its members and graduates had networks well beyond Harvard and Cambridge. I began by making sure we always had a resident tutor in East Asian Studies. When I look back at the names, I see what a talented group it was. In 1983, I invited Liu Haiping—then a Harvard-Yenching Fellow, now Professor of American Literature at Nanjing Universty—to join Adams House. Tim Brook (now teaching Chinese history at the University of Toronto) and his wife Margaret Taylor covered drama, East Asian Studies, and took care of their new baby. In 1985, when I interviewed a graduate student named Wu Hung for a tutorship, he told me that he was born in Southwest China, had wanted to be a painter, but during the Cultural Revolution was assigned to guard paintings in the Forbidden City and then sent to a labor camp where he developed “the habit of deciphering ancient hieroglyphics.” During his years as a resident tutor at Adams, Wu Hung invited Chinese painters—including Yuan Yensheng whose murals at Beijing Airport of the Water Festival and Song of Life were boarded up during the Cultural Revolution because of a few scantily clad figures—to spend time and give exhibits in the House. Yuan gave two of his works to Adams and gave me an ink-brush sketch of myself in Maoist poster-style. Wu Hung is now Distinguished Professor of Chinese Art History at the University of Chicago. The effervescent Hugh Shapiro (now Professor at the University of Nevada), John Weinstein ‘93 (Professor at Bard College at Simon’s Rock) and the incomparable Carsey Yee (who modestly described himself as a “gluten-intolerant Canadian”) complete the picture, but only suggest the years of exhibits, lectures, plays, films, not to mention the celebrations of Chinese New Year and the visits of the Mayor of Beijing and Han Xu, the Chinese Ambassador to the U.S. , and the generations of Chinese students who lived with us at Apthorp House.

Of course, the main reason that we decided to stay on at Adams was to enjoy the company of the continuing number of original and gifted students who chose to live here. The mid-‘80’s were not a particularly political time, but spearheaded by Damon Silvers ’86 (now Assistant General Counsel for AFL-CIO and one of two undergraduates invited in 1986 to join the Dining Hall workers’ union in negotiations with Harvard), Adams became the headquarters of the student movement dedicated to persuading Harvard to divest its financial holdings in apartheid South Africa. I still see them huddling and planning at the long tables along the windows on Arrow Street. I still see Constance Adams ’86 (now a space architect at NASA), wearing a film strip dangling from one ear, and the mock shanty town that she designed and help set up in the Yard while the police and the administration were sleeping. I still remember Cathy Schuyler ’85 (now Rev. Schuyler, pastor of Duluth Congregational Church) having her diploma withheld for six months because she was photographed participating in a demonstration. (The one and only time I was “called on the carpet” by my friend Derek Bok was when someone’s grandmother complained to him that I had praised Cathy at our diploma ceremony and awarded her a “diploma” signed by all her Adams classmates! I confessed. He smiled and asked me to try to behave myself. I promised to try, but really Adams House sometimes made that difficult.)

Over the years many of my tutees in English and History and Lit were Adamsians. I wish I had time and space to list them all, but I can’t forget the brilliance of Mary Bly ’85, Bonnie McDonald ’86, Jeff Rosen ’86 (Professor of Constitutional Law at Washington University), Melissa Weissberg ’86 (one of the great editors-in-chief of The Harvard Crimson), Alex Ross ’90 (whose music criticism in The New Yorker still gets an A+ from his tutor), and Rob Tobin ’93 (now Rev. Robert Tobin living in the rooms of John Henry Newman at Oriel College, Oxford where he is chaplain.)

I’m sure Gino didn’t design

the one that the House Committee

presented to the wife of the

Chinese ambassador at a formal

dinner that said, “Yale Sucks.”

She asked me what that meant

and The Crimson

—always on the lookout

for news in Adams

House–took a picture of me

with my face in myhands.

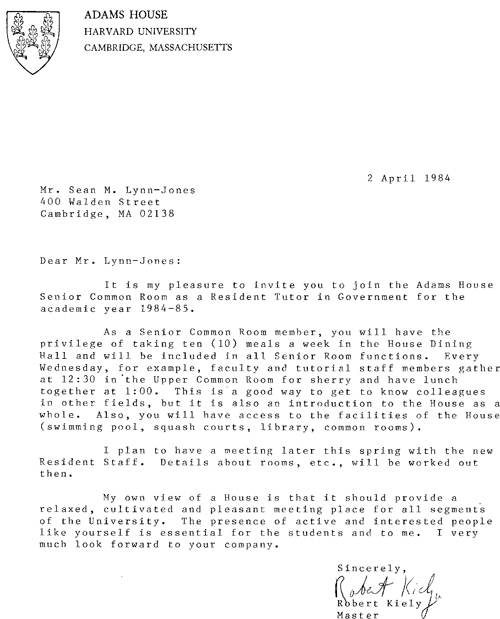

In appointing House Tutors, I had an unashamed prejudice in favor of Adams graduates. The students and I knew them and their talents. They knew us and, anyway, most of them didn’t really want to leave Adams after only three years. In the early and mid ‘80’s Aaron Alter ’79 was our happy Hawaiian law tutor; master sculptor Romolo del Deo ’82, art tutor; learned Hebrew scholar, Dan Frank ’77, tutor in Near Eastern Languages and Literature; brilliant Chris Shibutani, ’85 Science Tutor; Ceci Rouse ’86 (now Professor of Economics Cecilia Rouse at Princeton) was Economics Tutor while serving as Head Tutor in her department; Lori Paxton ’86 (who taught my 90 year old mother-in-law how to use a computer) was Business Tutor; multi-talented Inger Tudor ’87 was Drama and then Law Tutor; Gino Lee ’86 took over the Bow and Arrow Press, designing some of the most original posters, invitations, and T-shirts in the college. (I don’t know if it was Gino who designed the Adams T-shirt that said, “We’re all gay and we’re coming to get you.” I’m sure he didn’t design the one that the House Committee presented to the wife of the Chinese ambassador at a formal dinner that said, “Yale Sucks.” She asked me what that meant and The Crimson—always on the lookout for news in Adams House–took a picture of me with my face in my hands.)

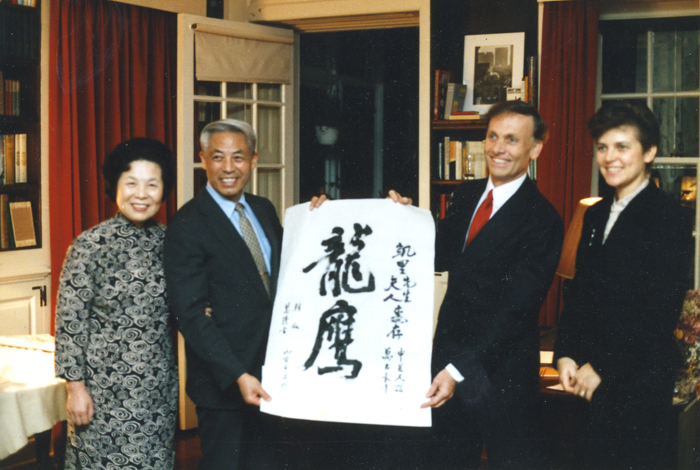

Film-maker and graphic novelist Yule Caise ’87, VES tutor, commented in his facebook entry (old style print on paper) that he was “proud of the fact that the Adams House Film Society is the only one in which students make films and screen them.” Later, writer/director/composer Roland Tec ’88 (whose opera Stained Glass Windows was performed in Sanders Theater with audience on stage and singers in the orchestra and balcony) was Drama Tutor; Renee Cheng ’85 (now Professor and Head of the School of Architecture at the University of Minnesota) and George Ho ’90 (a prize-winning painter living in Taiwan), were art tutors; Rhodes Scholar Joel Shin ’90 and Law student Jamila Jefferson ’94 were Pre-law tutors; Shirley Thompson ’92 (Professor of American Studies at the University of Texas, Austin) was tutor in Am Civ. Leo Trasande ’94 (now Co-Director of Children’s Environmental Health at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine) succeeded Jamie Ferrara (Professor of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology and Director of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, University of Michigan), Alan Hartford (Section Chief of Radiation Oncology at Dartmouth-Hitchcok Medical Center), and Samia Mora (Cardiologist at Fish Center for Women’s Health) in a great line of brilliant and dedicated Pre-medical Tutors who steered generations of Adamsians through the stressful process of applying to medical schools. It was always good to have a doctor in the House. They all gave advice and help well beyond the call of duty. When our nine year old grandson (now 20 and in full remission) was diagnosed with leukemia, our first thought was to telephone Jamie in Michigan. As always, he gave us and our daughter and son-in-law clear, expert, reassuring advice.

Adams always had a strong musical tradition. During the early ‘80’s when Beverley Taylor (presently Professor of Choral Conducting and Director of Choral Activities at the University of Wisconsin School of Music) was Music Tutor, Adams had its own madrigal singers. Bev was conductor of the Radcliffe Choral Society from 1978 to 1995 and was the first woman to conduct the Harvard-Radcliffe combined choirs and orchestra in a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at Sanders Theater. Later, resident composer and organist James Johnson persuaded me to accept the offer of Philips Brooks House to install its historic 19th century Hook and Hastings pipe organ, a beautiful instrument on loan at Radcliffe, in our Lower Common Room. Adams cannot take credit for the musical talent of its graduates—notably, Alan Gilbert ’89, Conductor of the New York Philharmonic or China Forbes ‘92 and Thomas Lauderdale ‘92 of Pink Martini—but we can take pride in their accomplishments. Composer/conductor Ben Loeb ’89 conducted an unforgettable Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony at midnight in the Dining Hall to a standing-room only audience from all over the campus. Pianist Hugh Hinton ’90 (now on the faculty of the Longy School of Music) became Music Tutor in 1991 and was given a key to Apthorp House so that he could practice for hours on the Steinway in our music room. Hugh generously performed at many events, large and small, but one that I was particularly grateful for was in the Lower Common Room at a dinner for the faculty of the English Department. My colleagues were not getting along. One half was not speaking to the other half. I was chair and was trying to make peace so, of course, I invited them to Adams. I gave no speech and I did not invite anyone to speak. I simply introduced Hugh during coffee and dessert. I still remember the hush in the room when he began to play one of Brahms’ Fantasies. Hard expressions melted; tentative smiles were attempted; happy days were (almost) here again for the Department of English!

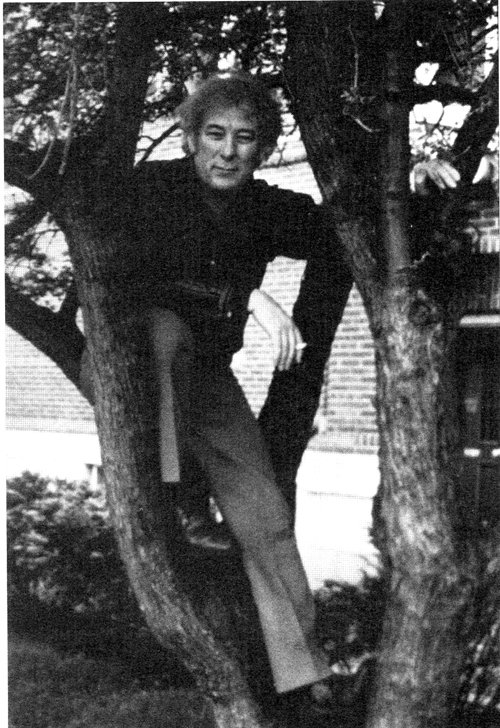

Seamus Heaney Up a Tree at Adams, 1995

The 1980’s saw the arrival of several newcomers who became “pillars” of Adams House. In 1983 a young Irish poet named Seamus Heaney moved into a modest guest suite in I-entry. I had discovered and admired his poetry when I was on sabbatical in the other Cambridge, but had never met him. Seamus and his wife, Marie who came for short visits from Dublin where she was caring for their small children, became our friends and friends of so many in Adams House. Seamus turned out not only to be a gifted poet, but a good-natured, sociable one, and a grand reader of his own poetry. Along with Chinese New Year, Soul Night, Drag Night, Cinco de Mayo, the Kielys instituted an annual St. Patrick’s Day Tea during which I paid homage to my Irish ancestors by bar-tending and serving Black-and-Tans (Guinness and Harp). Seamus always came and read poetry. Often he brought Irish friends, fiddlers, and penny whistle players. Sometimes he had to stand on a table or chair in my study in order to be heard amid the throngs. Students tried the Irish jig and in the late ‘90’s they were actually taught Irish Dancing by Meeghan Piemonte ’99. (East Apthorp must have turned over in his grave!) When Seamus was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995, he telephoned from Dublin during a Friday Tea so we could share the great news with his friends and students at Adams.

In 1984 another member of the Adams House Hall of Fame—Vicki Macy—came to be Assistant to the Master. I had known Vicki when she was working for the dysfunctional English Department and thought I would do her and Adams House a favor by inviting her to preside over the House office. I could not have made a better choice. In the days before computers and email, the House Office was the Command Center of Adams where all student, faculty and outside inquiries were made; appointments arranged; schedules set; rooms reserved; events planned; problems solved. The phone rang constantly and people were in and out all day long. Vicki took care of my correspondence and House commitments; kept track of what was going on everywhere in the public spaces of the House; and, perhaps most important of all, was a sympathetic ear to the worries and headaches of the students and tutors who came just to see her. Every Monday morning, the Senior Tutor and assistant, the director of the Dining Hall, the Superintendent, and I met in her office to go over the successes and failures of the previous week and to plan the week ahead. I actually looked forward to these meetings. I now wonder why. I think it was because Vicki had a calming presence even when the rest of us were stressed over one thing or another.

When the Senior Tutor’s assistant went on half-time in 1988, a bearded artist and novelist named Otto Coontz appeared on the scene (after “canoeing in the Venezuelan jungle”) looking for a job that would give him time to paint and write. Adams and Otto were a perfect fit. In a quiet, modest way, Otto managed to keep student records and several generations of Senior Tutors in order while dispensing encouraging advice to gay students and the many budding artists and writers in the House. Otto soon took over fulltime duties as assistant to the Senior Tutor and turned his office into a mini-museum of Adams memorabilia. When he announced his retirement this past spring, hundreds of Adamsians, past and present, came to wish him well in his new life in California.

Among other highlights of the 1980’s that come to mind was the appointment in 1989 of Janet Viggiani, the first female Senior Tutor of Adams House. A graduate of Smith, Janet was Assistant Dean for Co-Education and Coordinator of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual Network. Among the group of exceptional Senior Tutors that I was lucky enough to work with, Janet stood out for her combination of good humor, self-discipline, warmth, and courage. When she was diagnosed with an advanced form of breast cancer, she asked for a one semester leave of absence to drive alone across country—something she had always wanted to do—in order to think over her options. She sent me a postcard from the Grand Canyon saying she had climbed to the bottom and up again and had had the time of her life. She returned to Adams, served as Senior Tutor for another three years, then went to Law School and practiced law, defending women from discrimination and harassment until her death ten years later.

Women had long been a strong presence in the student body and on the tutorial staff of Adams. Professor of American Literature Kathryne Lindberg and, later, Rebecca Spang ’85, also served with stamina and dash as Senior Tutors. Our first woman Physics Tutor, Lisa Randall, was appointed in 1984. Lisa became the first tenured female Professor of Theoretical Physics at Harvard and has continued to show her Adams colors by writing the libretto of an opera. Although I was accustomed to being asked interesting and unusual questions and favors by Adamsians, I was particularly surprised and touched when Suzanne Litke ’87 and Lisa Myers ’86 asked if I would preside at their commitment ceremony/wedding at the Hasty Pudding. At that time, gay marriage was not yet legalized in Massachusetts and they could not find a rabbi willing to officiate. I suggested an Emily Dickinson poem, but otherwise the ceremony was of their devising. When the day came, I was probably more nervous than the brides. It seemed as though half of Adams House was there in front of the big fireplace in the old Hasty Pudding. My opening lines seemed inevitable and they came from the heart because they expressed what I had been feeling for Adams House for a long time: “Dearly beloved, we are gathered together to celebrate.”

In 1990, Jana and I and our 13 year old daughter Maria drove across the country to Stanford for the first term of a sabbatical year and then flew to Florence where I was Visiting Professor at Harvard’s Villa I Tatti for the spring semester. When we returned, Adams House of the ‘90’s was beginning to look a little different from the one we had come to in 1973. By the late ‘80’s the tunnels had been painted with murals by students. When the House Committee had suggested that students sign up for a space to paint self portraits along the gray tunnels connecting Adams buildings, the Superintendent said, “No way,” the deans, Buildings and Grounds, etc., etc. would never allow it. So we decided, while the Super was away for the weekend, to let students work day and night under the supervision of the House Committee. I provided the paint; they provided the schedule and clean-up. On Monday morning the Super was not happy, but when I brought Deans Fred Jewett and Archie Epps for a tour, they had to admit that it looked fantastic. “Very Adams! Very Adams!”

While we were in Italy, Senior Tutor Janet phoned to say that the Athletic Department (in charge of maintaining the Adams pool) reported that minor leaks had become major and were undermining the foundation of the nearby kitchen. The pool was emptied and closed. There are many legends about the Adams pool, about half of which are probably true. One that is not true is that the pool was closed because of nude swimming which had been permitted during certain hours for many years. In the late ‘80’s , the old pumps and filtration system were constantly breaking down and failing to keep the pool clean. The water level fell, the water became murky, and fewer and fewer people swam with or without suits. When the pool was closed, it was hoped that the University would repair the problems and reopen it since it was a hugely expensive project well beyond the Adams budget. After a few years, it became clear that this was not going to happen and that a locked historic space with a 10 foot drop to a hard concrete bottom was both an invitation and a hazard to curious Adamsians. When the young actor/director Art Shettle became Drama Tutor in 1993, he and I began thinking of other uses for the space. Finally, Art and Superintendent Billy Long (formerly a carpenter) drew up plans and a modest budget for a theater. We found seats in storage from an old lecture hall; Billy and friends helped with the building of the stage; and I begged money from Dean Jewett. In the spring, the Swimming Pool Theater had its official opening with (what else?) La Cage aux Folles and the rest is history (or myth), whichever you prefer.

The Sun and the Moon over the Conservatory.

For years, one of my dreams for Adams House was that the open space outside the Gold Room between the Dining Hall and C-entry could be roofed over so that it could be used as a small dining area/meeting room all year long. Year after year, deans said it was too expensive and architects said it couldn’t be done. Then in 1997, I found an ace in my pocket. I was heading to Stanford again for my last sabbatical as Master when Dean Jeremy Knowles asked if I would fly back for several days to chair what promised to be a tense and important committee meeting concerning the future of the ART. He made the mistake of promising that he would do me a favor “some day.” I said that I was about to leave Adams in two years and that the “day” had arrived when my dream for Adams House might be fulfilled. I told him about crowding in the Dining Hall and the importance of small meeting spaces for seminars, discussions, etc. He then did something terrific. He set a budget and told me that I could appoint a small group of students and tutors to interview and select an architectural firm and collaborate with them in the designs of the space. Several firms came up with bland, unimaginative plans, but one spent a lot of time looking around the dark and intriguing corners of Adams, made a collage of photographs, and genuinely loved the quirky originality of our spaces. We chose them and worked with them, enjoying every minute. It was their idea to copy the glass ceilings of Waterloo Station to keep off the rain and let in the light. It was our idea to have wrought iron sconces and chandeliers in the shapes of oak leaves. It was their idea to work the letter A into the ceiling struts. The Dean was so pleased with their work that he assigned the renovation of the kitchen and serving area to the same firm. Our committee proposed the color of the tiles in the serving area and the stained glass windows with quotes from FDR and Seamus Heaney (although we didn’t expect them to be backwards!)

No year or class at Adams was quite like the one before, but in 1993 there was a particularly wonderful and memorable surprise. In May of that year, Pre-medical Tutor Jamie Ferrara, his wife Flora and former Senior Tutor John Hildbidle and his wife Niki invited Jana and me to a formal dinner for a birthday or anniversary, I forget which. They picked us up at 5 and began driving around Cambridge saying they had to go pick up Niki. After twenty minutes or so, Flora said she had left her purse at Apthorp House and we had to go back. We all got out of the car and began walking to the front door of Apthorp when there was an eruption of cheers and applause in Randolph Court from hundreds of students, tutors, alumni, President and Mrs. Bok, and the deans of the College. It was a surprise celebration of our twentieth year at Adams! Jana and I had begun to suspect something fishy was going on, but not this! The planning had been amazing and been done by Vicki, the tutors, students, and alumni without our knowing a word of it. We were doubly touched because we saw the celebration as not only “for us” but for all of Adams House. It was a perfect afternoon in May. Champagne corks popped; Seamus read a poem; speeches were delivered; and as the evening came, there was a splendid banquet in the Dining Hall, dessert in the Gold Room which had been impressively decorated by Sarah Dawidoff ’87 with an enormous mobile of ping-pong balls suspended from the ceiling; followed by simultaneous displays of Adams talent: concerts in the Lower Common Room; poetry readings in the Library; an art exhibit, a play, a theatrical event featuring Tanya Selvaratnam ‘93 as Pantherella; all concluding with a dance in the Dining Hall.

It probably sounds strange to refer to Adamsians as saintly, but two remarkable members of the House who passed away during our time here come to mind. Ben Teel became a Resident Tutor in Romance Languages in the early ‘80’s. Ben was a talented, soft-spoken, gentle character who spent hours every week, when not working on his thesis, counseling and teaching English to poor Haitian immigrants. Fluent in Creole as well as French and Spanish, Ben was a generous and patient friend to all at Adams who knew him. A Ben Teel Prize was established for an Adams senior who has made a significant contribution to the welfare of minorities in need. I met Navin Narayan ’99 at our welcoming dinner for sophomores in 1997 and never forgot him. Somehow we got talking about meditation; he told me about a temple to a snake god near where his grandparents lived in India; and how his favorite season was the monsoon when he could splash around in the rain. In high school, Navin led Red Cross rescue volunteers to flooded areas in Texas and other states. During summers, he took a camera to the poorest districts of Indian cities and interviewed children who had been left there by parents who could not afford to feed them. His dream was to become a physician, return to India, and build clinics and homes for these children. When he became ill, Navin had to leave school and eventually succumbed to a brain tumor. In the last months before he died, I phoned him every week to report on doings at Adams. Although his voice grew fainter and fainter, he always sounded serene and happy to hear from us. A Navin Narayan Lecture on a theme in the spirit of Navin’s life is given at Adams House each year.

One of the privileges and responsibilities of Masters is to receive visiting dignitaries, some of whom can be a headache, but most of whom are a pleasure. Some of my favorites were Isaac Bashevis Singer (who came to lunch at Apthorp House to celebrate Purim with us and a group of Jewish students); resident playwright Adrienne Kennedy (whose plays were performed in the LCR); conductor Kurt Mazur (who had been the mentor of music tutor Jim Ross ‘81); Norton Lecturers Nadine Gordimer and Umberto Eco (who after dinner drew a map of Italy on a napkin showing that his ancestors and my mother’s from Piemonte were the true Italians); our dear friend Jill Ker Conway (the first woman president of Smith); and Vaclav Havel (who took a long nap in our guest room.)

Bob Kiely with Tennessee Williams 1982

Although he did not stay with us, it was because of Adams House that I was asked by the University Marshal to escort Tennessee Williams when he received an honorary degree in 1982. At the Honorary Degree Dinner the night before Commencement, Williams (a short, shy man) was nervous and a bitoverwhelmed by Harvard formality, but after dessert and a little wine when a student group came in to sing, he smiled, relaxed, and taking my hand and that of the elderly lady next to him, said (like one of his characters): “I just want to be surrounded by beautiful people.” The next morning when I met him at Johnson Gate for the procession, he seemed anxious again because he was in a sport jacket, had no academic gown, and felt out of place at Harvard. I tried to reassure him, but he became more tense when we were told to go into Massachusetts Hall where the Honorands were to sign a guestbook. Inside the reception room there was a whirl of red gowns and “important” people standing and chatting as if at a Cambridge cocktail party. I thought Williams was about to back out when he and I saw two very small nuns (ignored by everyone) sitting on a couch across the room saying the rosary. “My God!” Williams whispered, grabbing my arm, “That’s Mother Teresa!” I had been on the Honorary Degree Committee and knew she would be there though she had not come to the dinner. Tennessee (he had become “Tennessee” by then) said, “Will you introduce me to her?” I told him that I didn’t know her, but “Yes, of course” that’s what Masters are supposed to do: introduce everybody to everybody else. So over we went through the milling crowd of crimson and I—in the strangest introduction I have ever made—said respectfully to the tiny, wrinkled nun, “Mother Teresa, this is Tennessee Williams.” She looked up kindly, obviously having no idea who Tennessee Williams was. And then something extraordinary happened that I am almost positive no one else in the room saw. Tennessee fell to his knees and put his head on her lap. And she patted his head and blessed him. After that and for the rest of the day, he beamed. During the procession, he said to me, “Now I know why I came to Harvard.” (I have always thought that this was a deciding factor in his leaving some of his papers to Houghton.)

Adams Drag Night 1998

Our last two years at Adams were bittersweet. Our youngest daughter Maria ’99, who was born in 1977 and brought up as an Adamsian, was about to graduate. It was time to let go and let others have the fun. Music, poetry, soccer (coached by the great Dennis Skiotis), and theatricals (on and off stage) continued to the very end. At my first Drag Night, I had worn a mask and gone around the Dining Hall sitting on people’s laps, hoping they didn’t know who it was. At our final Drag Night, I dressed as Mother Superior, several tutors and students dressed as nuns, and we danced and lip-synched “How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria?” There is no simple way to sum up twenty-six years. I can only say that Adams House became inseparable from my experience as a professor at Harvard. It was a constant source of my own education, an ever-changing, varied, enlivening flow of tolerance, good humor, talent, ideas, friendships, and challenges. I really do believe that during those years there was no place at Harvard—or anywhere—quite like it! I wish I could mention everyone who enriched our lives, but the best I can do here is to send these few memories and my gratitude and warmest greetings to all Adamsians, past, present, and yet to come.