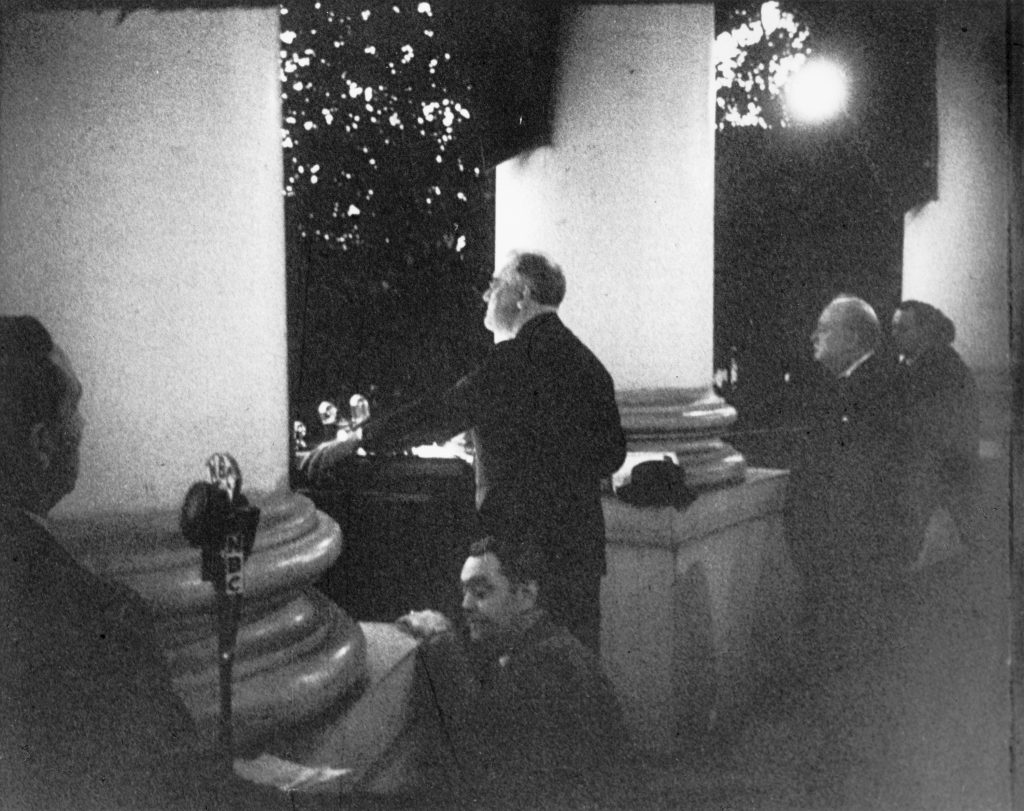

Roosevelt addresses the crowd at the Christmas tree lighting ceremony from the White House South Portico on December 24, 1941. Churchill can be seen on the right. (FDR Presidential Library)

It was Christmastime when Prime Minister Winston Churchill arrived in Washington on December 22, 1941—two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor and eleven days after Hitler audaciously declared war on the United States.

For eighteen months Churchill had wooed Roosevelt, cajoling, charming, and even begging him to bring the United States into the war against Germany. Now Churchill’s prayers were answered: the United States would certainly enter the war. On learning of the attack, Churchill later wrote, “Being saturated and satiated with emotion and sensation, I went to bed and slept the sleep of the thankful and the saved.”

Churchill had come to Washington to make sure that earlier agreements of an Anglo-American alliance against Germany (should America enter the war) remained firm in the face of the Pearl Harbor attack. Understandably, the American people had an overwhelming desire to strike back at the Japanese. Churchill needed to turn them from thoughts of revenge to Britain’s view of the realities of the Axis threat. His task was made more difficult by Japan’s stunning victories in the weeks following Pearl Harbor. In the Philippines American troops were trapped on the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula and the Rock of Corregidor. Within a matter of days, Guam, Wake, and Hong Kong had fallen. American territories were being invaded and American lives lost. Americans wanted to throw everything they had against the Japanese.

Yet there was Britain’s precarious position to consider: if the Soviets fell, Hitler would throw his full strength into the temporarily delayed invasion of the United Kingdom. If Britain fell, what would be next for the United States? Germany was the more powerful of the foes. In an Anglo-American alliance, Churchill’s longstanding policy was the defeat of “Germany First.” He needed to make sure that the great power of the American war machine was leveled first against Hitler and second against the Japanese. Fortunately, Roosevelt agreed with him. But his position was not without dissent from some military advisors—and critics in the press and public.

Whatever his motives, Churchill’s presence was a tonic to the shattered Americans. On December 23 he joined FDR in a news conference in the Oval Office. More than two hundred journalists crowded into the room, some using edges of the president’s desk to take notes. “Wearing polka dot bow tie, a short black coat, and striped trousers,” Doris Kearns Goodwin tells us, Churchill

stared imperturbably into space, his long cigar between his compressed lips as Roosevelt spoke. When the time came for the prime minister to speak, reporters in the back called out that they could not see him. Asked to stand, Churchill not only complied, but scrambled atop his chair. “There was a wild burst of applause and then cheering,” The New York Times reported, . . . “as the visitor stood there before them, . . . with confidence and determination written on the countenance so familiar to the world.” (p. 303)

Bernard Baruch was among those invited to the White House that Christmas season. He “believed that Churchill’s visit would ‘galvanize’ American public opinion,” according to Eleanor Roosevelt biographer Blanche Wiesen Cook.

With the Pacific fleet in ruins, Wake Island fallen, Singapore besieged, and the Philippines invaded, Baruch considered Churchill “the best Christmas present” to restore heart and hope to the Allied world. “The pink-cheeked warrior in the air raid suit” was the leading symbol of resistance to the Blitz: “Do your worst, we can stand it,” his presence seemed to say. “We won’t crack up.” (Cook, pp. 409–410).

Wartime blackout regulations and tight security precautions were already in place in Washington; nevertheless, Roosevelt insisted on lighting the national Christmas tree. Various reports describe the event. “Our strongest weapon in this war is that conviction of the dignity and brotherhood of man which Christmas Day signifies,” he declared. Churchill joined Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt on the balcony of the White House before a crowd of 20,000 and in a national radio broadcast that reached millions. “Let the children have their night of fun and laughter,” Churchill said, and then:

Let the gifts of Father Christmas delight their play. Let us grown-ups share to the full in their unstinted pleasures before we turn again to the stern task and formidable years that lie before us, resolved that, by our sacrifice and daring, these same children shall not be robbed of their inheritance or denied their right to live in a free and decent world.

On December 26 Churchill addressed a Joint Session of Congress, declaring himself half-American. “By the way, I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British instead of the other way around, I might have got here on my own.” Much to Eleanor Roosevelt’s distress (who had a more internationalist vision), he stressed the unity and implied superiority of the English-speaking world, speaking of the “outrages they have committed upon us at Pearl Harbor, in the Pacific Islands, in the Philippines, in Malaya and the Dutch East Indies.”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin Roosevelt give a joint press conference in the Oval Office of the White House, December 23, 1941. (FDR Presidential Library)

The White House hosted a steady stream of diplomatic and military dignitaries during Churchill’s two-week visit. Meetings were held every day and long into the night—including Christmas day when a War Council was held from 5:30 to 6:45 pm. The war planners set themselves to the business at hand: North Africa, the Pacific and Southeast Asia, military strategy, war production, tonnage, and the Far East were among the subjects of talks. Ambassador Maxim Litvinov from the USSR, Prime Minister Mackenzie King of Canada, and the chiefs of the American Republics of South America and the Missions of the Allied Power and Refugee Governments came and went.

Since Churchill’s arrival he and FDR had been working on a Joint Declaration of Unity and Purpose for the Allies. As they laid the groundwork for war, they also began to frame the peace. It was FDR who suggested to Churchill on the morning of December 29th the name that would signify both war power and the promise of peace: the United Nations.

On New Year’s Day Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, Maxim Litvinov of the USSR, and T. V. Soong of China signed the Declaration of the United Nations. An exultant Churchill declared, “Four fifths of the human race” has resolved Hitler’s end.

The next day twenty-two additional countries signed: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Poland, Union of South Africa, and Yugoslavia. Subsequently Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Egypt, Ethiopia, France, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Liberia, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, Uruguay, and Venezuela signed.

Those countries that signed by March 1945 would become the founding members of the United Nations.

The Declaration read in part:

The Governments signatory hereto,

Having subscribed to a common program of purposes and principles embodied in the Joint Declaration of the President of the United States of America and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland dated August 14, 1941 known as the Atlantic Charter.

Being convinced that complete victory over their enemies is essential to defend life, liberty, independence and religious freedom, and to preserve human rights and justice in their own lands as well as in other lands, and that they are now engaged in a common struggle against savage and brutal forces seeking to subjugate the world,

Declare:

(1) Each Government pledges itself to employ its full resources, military or economic, against those members of the Tripartite Pact and its adherents with which such government is at war.

(2) Each Government pledges itself to cooperate with the Governments signatory hereto and not to make a separate armistice or peace with the enemies.

What then was this Atlantic Charter that underpinned the entire agreement?

It was nothing less than a declaration of goals for the postwar world, an instrument for peace forged in the exigencies of war: “after the final destruction of Nazi tyranny, [it envisioned] . . . a peace which will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safety within their own boundaries, and which will afford assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.”

To ensure that world, Roosevelt and Churchill called for permanent disarmament and envisioned a “permanent system of general security.”

All of the nations of the world, for realistic as well spiritual reasons, must come to the abandonment of the use of force. Since no future peace can be maintained if land, sea, or air armaments continue to be employed by nations which threaten, or may threaten aggression outside of their frontiers, [the signatories] believe, pending the establishment of a wider and permanent system of general security, that the disarmament of such nations is essential.

Churchill had come to the Atlantic Conference seeking American entry into the war against Hitler to preserve the British Empire. The Atlantic Charter was Franklin Roosevelt’s vision, a reimagining of the lost promise of the League of Nations and Woodrow Wilson’s failed vision for an end to all war. Out of it grew the United Nations—an ambitious idea for a post-war world of peace, disarmament, decolonization, democratic self-determination, respect for human rights, and free trade.

This is the legacy of Christmas 1941—and a reminder of work we have yet to complete.

Sources:

Cook, Blanche Wiesen. Eleanor Roosevelt: The War Years and After, Volume 3, 1939–1962. New York: Viking, 2016.

Goodwin, Doris Kearns. No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994.