In commemoration of 78th Anniversary of FDR’s death, we share a tribute to the 32nd U.S. President written by Dhruthi Dev Gurudev, an tenth-grader in Tamil Nadu, India.

Writing in her second language, she hopes to raise awareness of FDR’s history in South Asia, in defense of democracy.

A TRIBUTE TO FDR

I am, Dhruthi Dev Gurudev quiet pleased to join the 78th (12/4/2023) Anniversary of our great leader Franklin Delano Roosevelt and I have great pleasure in delivering this address and pay my heart warming tribute to FDR.

A total of 413 days (12/4/2023) have been passed since the beginning of Russian Ukraine War and there is no real science of a way out of a conflict. Neither side appears primed for an outright military victory and progress at the negotiating table seems just as unlikely for the civilian caught in a cross fire, that means the bloodshed and suffering brought on by the war has no discernible. The war might be the reappearance of psychopathology of Adolf Hitler in the Humanity.

In the 78th anniversary might be most disharmonious celebration of FDR’s Anniversary since 1946.

Still the celebration of 78th Anniversary and remembrance of FDR might bring in explication to solve not only the current war but a permanent relief to the civilians from war and for the analyst to exuberance new concepts and means. It might not be wrong to state that United Nations is the blood and flesh of FDR and it is the responsibility to ensure WORLD PEACE BY UNITED NATIONS.

History saved and preserved documents, images etc individuals or group have the highest responsibility to investigate and summarise such documents for the betterment of. the world in which they live.

In this article the contribution of FDR to the humanity is submitted as a reminder as well as the important of the humanitarian’s values. To emphasise the role of UNITED NATIONS, Extract of League of Nations are also stated.

LEAGUE OF NATIONS

In an interview on the question of Anglo-American relations as a factor in world security, published by The Sunday Observer of London on December 2, 1934, United States Ambassador Bingham made the following significant statement:

“An entirely new situation has arisen in the United States itself which makes possible now what has not before been possible—I frankly admit it—since the war. It is a commonplace of British and European comment on American diplomacy that, the United States proposed the formation of the League of Nations yet has not joined it, and proposed the formation of the World Court yet has not adhered to it; in short, that in the words of the old epigram, the American President proposes but Congress disposes. That criticism was fair, but it no longer holds.

“No American President was ever in the position that President Roosevelt is now in. He is not merely a Democratic President, he is a national President, supported by two-thirds of the House of Representatives and the Senate. No American President before him increased his majority in the mid-term election. But the point is this: He is not only wise, statesmanlike, and fair to every party and interest in the United States; you may depend upon it, he will never propose anything to Congress which he is not certain in advance that Congress will endorse.

“That is the great new thing. If your government reaches an understanding on any question with President Roosevelt, it reaches a certain, binding, and lasting understanding with the American nation…. America’s house at home is being put in order. Abroad she offers a new reliable basis for confident diplomacy.”

After he became President, in an address at the annual dinner of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation on December 28, 1933, Roosevelt spoke of the League in more friendly terms. In conclusion the President said: “We are not members and we do not contemplate membership. We are giving cooperation to the League in every matter which is not primarily political and in every matter which obviously represents the views and the good of the peoples of the world as distinguished from the views and the good of political leaders, of privileged classes, or of imperialistic aims.”

As the situation in Europe escalated into war, the Assembly transferred enough power to the Secretary General on 30 September 1938 and 14 December 1939 to allow the League to continue to exist legally and carry on reduced operations. The headquarters of the League, the Palace of Nations, remained unoccupied for nearly six years until the Second World ended.

At the 1943 Tehran Conference, the Allied powers agreed to create a new body to replace the League: the United Nations. Many League bodies, such as the International Labour Organization, continued to function and eventually became affiliated with the UN. The designers of the structures of the United Nations intended to make it more effective than the League.

The final meeting of the League of Nations took place on 18 April 1946 in Geneva. Delegates from 34 nations attended the assembly. This session concerned itself with liquidating the League: The League is dead. Long live The United Nations.

UN 75

Declaration on the commemoration UN75 was released on June 25, 2020.

It states as given below; Born out of the horrors of WW II , the United Nations common endeavour for humanity, was established to succeeding generations from the scourge of war, etc etc ……

The UN75 celebrations were heartbreak for many as United Nations failed to bring in the full life history of United Nations in its 75 key documents that are shaped by United Nations. FDR’s most sincere and effective work in establishing United Nations had missed in UN 75 celebration.

The US President Harry S. Truman in 1945, had failed in one account by not incorporating the Founder of United Nations as the late US President Mr Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Founders Day 1st January. UN celebrates more than 100 Days in a year but failed to celebrate 1st of January as Founder Day and the Founder is Franklin Delano Roosevelt. UN has stretched its hands on many fields but the main object the World Peace needs more attention. The extract of Prime Minister Narendra Modi when he addressed the United Nations General Assembly on September 28, 2014 substantiate the arguments.

“There are no major wars, but tensions and conflicts abound; and, there is absence of real peace and uncertainty about the future. An integrating Asia Pacific region is still concerned about maritime security that is fundamental to its future. Europe faces risk of new division. In West Asia, extremism and fault lines are growing. Our own region continues to face the destabilizing threat of terrorism. Africa faces the twin threat of rising terrorism and a health crisis. Terrorism is taking new shape and new name. No country, big or small, in the north or the south, east or west, is free from its threat. Are we really making concerted international efforts to fight these forces, or are we still hobbled by our politics, our divisions, our discrimination between countries. We welcome efforts to combat terrorism’s resurgence in West Asia, which is affecting countries near and far. The effort should involve the support of al! countries in the region. Today, even as seas, space and cyber space have become new instruments of prosperity, they could also become a new theatre of conflicts. Today, more than ever, the need for an international compact, which is the foundation of the United Nations, is stronger than before. While we speak of an interdependent world, have we become more united as nations? Today, we still operate in various Gs with different numbers. India, too, is involved in several. But how much are we able to work together as G1 or G-All? On the one side, we say that our destinies are inter-linked, on the other hand we still think in terms of zero-sum game. If the other benefits, I stand to lose. It is easy to be cynical and say nothing will change; but if we do that, we run the risk of shirking our responsibilities and we put our collective future in danger. Let us bring ourselves in tune with the call of our times. First, let us work for genuine peace, No one country or group of countries can determine the course of this.”

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi appears to have directly rebuffed Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, telling Russian President Vladimir Putin that now is not the time for war. In what was the latest in a series of setbacks for the Russian leader, Modi told him of the need to “move onto a path of peace” and reminded him of the importance of “democracy, diplomacy and dialogue”.

The comments from Modi came during a face-to-face meeting on Friday, on the sidelines of a regional summit, and highlighted Russia’s increasing isolation on the diplomatic stage. They came just a day after Putin conceded that China, too, had “questions and concerns” over the invasion.

All the world leaders extended their full support and said PM Modi was right when he said this is not time for war. French President Emmanuel Macron told world leaders at the UN General Assembly session that Prime Minister Narendra Modi was right when he told Russian President Vladimir Putin that this is not the time for war.

The soviet Empire was made up of Soviet Socialist Republic in the period 1982-1992 and Russia was officially known as Russian federation and Ukraine was one among the 15 countries. Ukraine is now a household name and people aware that Ukraine is wheat-bowl country. In the family of Russia and 15 -member countries, Russia should/must be the strongest, the parent body. Siberians are killing Siberians and it must be stopped. Further it should not be allowed to spread. United Nation along with leaders of Non- Aligned countries should end the Russia- Ukraine war at the earliest. If the war continues, all the possibilities for disturbances in that area to certify their individual strength, not wise to predict the worst by an individual. Let us pray that Almighty and the soul of FDR bless us for World Peace.

Truth is always bitter and also the very concept of objective truth is fading. So in celebrating the anniversary, it might be home or country, the past is remembered and the Truth sustain. The anniversary celebration of FDR too reminds the world- WORLD PEACE.

UNITED NATION had not its birth over table discussions, rather it is blood and flesh of FDR. By founding UNITED NATIONS, FDR successfully get rid of Nazi tyranny and Japanese militarism.

The WWII broke out on September 1, 1939 and by 1941, Nazi captured entire Europe and strongly fighting to capture UK. Europe was burning, Americans are not to enter the war and the Congress refused any military help to UK, hoping it may all be used against them if UK was captured by Nazi. The only one American differed from this, FDR.

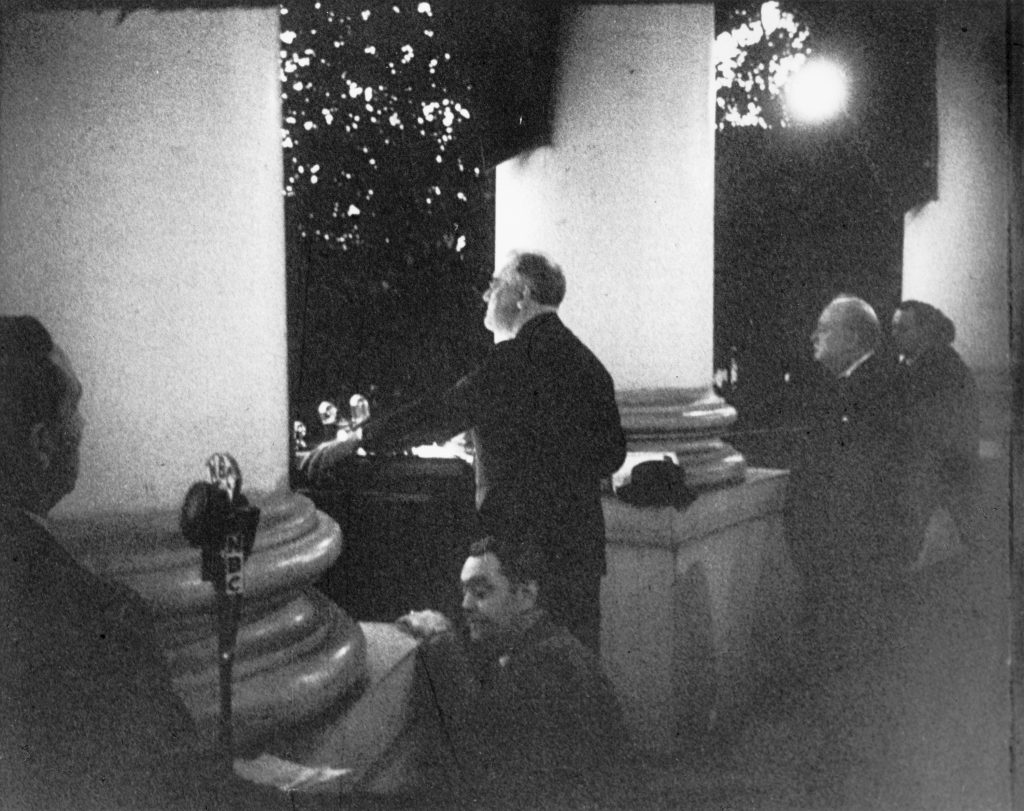

FDR delivered speech to congress on January 6,1941 known as his Four Freedoms Speech in which he described his vision for extending American ideals throughout the world and the extract:

“I address you, the Members of the members of this new Congress, at a moment unprecedented in the history of the Union. I use the word “unprecedented,” because at no previous time has American security been as seriously threatened from without as it is today.

“War began in Europe in 1939. By 1940 Adolf Hitler had conquered France, and Great Britain stood on the verge of military collapse. Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his State of the Union speech on January 6, 1941. In it he laid out national policy and, in a famous passage, named what he considered the four essential human freedoms. His speech follows.

“Since the permanent formation of our Government under the Constitution, in 1789, most of the periods of crisis in our history have related to our domestic affairs. And fortunately, only one of these–the four-year War Between the States–ever threatened our national unity. Today, thank God, one hundred and thirty million Americans, in forty-eight States, have forgotten points of the compass in our national unity.

“And in like fashion from 1815 to 1914–ninety-nine years–no single war in Europe or in Asia constituted a real threat against our future or against the future of any other American nation.

“During sixteen long months this assault has blotted out the whole pattern of democratic life in an appalling number of independent nations, great and small. And the assailants are still on the march, threatening other nations, great and small.

“Therefore, as your President, performing my constitutional duty to “give to the Congress information of the state of the Union,” I find it, unhappily, necessary to report that the future and the safety of our country and of our democracy are overwhelmingly involved in events far beyond our borders.

“As a nation, we may take pride in the fact that we are soft-hearted; but we cannot afford to be soft-headed.

“We must always be wary of those who with sounding brass and a tinkling cymbal preach the “ism” of appeasement.

“We must especially beware of that small group of selfish men who would clip the wings of the American eagle in order to feather their own nests.

“As long as the aggressor nations maintain the offensive, they-not we–will choose the time and the place and the method of their attack.

“And that is why the future of all the American Republics is today in serious danger.

“That is why this Annual Message to the Congress is unique in our history.

“That is why every member of the Executive Branch of the Government and every member of the Congress face great responsibility and great accountability.

“The need of the moment is that our actions and our policy should be devoted primarily–almost exclusively–to meeting this foreign peril. For all our domestic problems are now a part of the great emergency.

“The Congress, of course, must rightly keep itself informed at all times of the progress of the program. However, there is certain information, as the Congress itself will readily recognize, which, in the interests of our own security and those of the nations that we are supporting, must of needs be kept in confidence.

“For what we send abroad, we shall be repaid, repaid within a reasonable time following the close of hostilities, repaid in similar materials, or, at our option, in other goods of many kinds, which they can produce and which we need.

“The happiness of future generations of Americans may well depend upon how effective and how immediate we can make our aid felt. No one can tell the exact character of the emergency situations that we may be called upon to meet. The Nation’s hands must not be tied when the Nation’s life is in danger.

“I have called for personal sacrifice. And I am assured of the willingness of almost all Americans to respond to that call.

“In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

“The first is freedom of speech and expression–everywhere in the world.

“The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way–everywhere in the world.

“The third is freedom from want–which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants-everywhere in the world.

“The fourth is freedom from fear–which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbour–anywhere in the world.

“This nation has placed its destiny in the hands and heads and hearts of its millions of free men and women; and its faith in freedom under the guidance of God. Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere. Our support goes to those who struggle to gain those rights and keep them. Our strength is our unity of purpose.

“Since the beginning of our American history, we have been engaged in change—in a perpetual peaceful revolution—revolution which goes on steadily, quietly adjusting itself to changing conditions—without the concentration camp of the quick-lime in the ditch. The world order which we seek is the cooperation of free countries, working together in a friendly, civilized society.

“This nation has placed its destiny in the hands, heads and hearts of its millions of free men and women, and its faith in freedom under the guidance of God. Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere. Our support goes to those who struggle to gain those rights and keep them. Our strength is in our unity of purpose.

To that high concept there can be no end save victory.”

On January 10, 1941 FDR introduces the lend-lease program to Congress and the act on approval of Congress. FDR enacted the lend-lease act March 11, 1941. The UK was not the only Nation, and over the course of war, the United States contracted lend-lease agreement with 30 countries. Winston Churchill later referred to the initiatives as “the most unsordid act” one nation had ever done by another. FDR primary motivation was not altruism or disinterested generosity. Rather, Lend – Lease was designed to serve American interest in defeating Nazi Germany without entering the war, until the American military and public was prepared to fight.

American President FDR and UK Prime Minister issued a joint declaration on August 14,1941 known as Atlantic Charter. This declaration was signed by US, UK, USSR, and the nine governments of occupied Europe on September 24,1941. To the great surprise, the Japanese bombed Pearl harbour on December 7, 1941 and invited US into the war.

FDR coined the name “United Nations” to refer to the Allied Powers of WWII and Churchill accepted the idea. On December 29, 1941 two line text of “Declaration of United Nations “ was drafted at the White House.

President Roosevelt, PM Churchill, Maxim Litvinov of the USSR, T V Soong of China signed the document on New Year Day 1942 and the next day the representative of 22 countries were signed the declaration.

The government’s signatory hereto declares:

“Each government pledges itself to employ its full resources, military or economic, against those members of the Tripartite Pact and its adherents with which such Government is at war.

“Each government pledges itself to cooperate with the governments signatory hereto and not to make a separate armistice or peace with the enemies.”

To the Banyan size grown United Nations’ seed is the above two-line declaration and almost lost in all memories.

The war in progress and FDR was on his way in the formation United Nations. Carrying 10 pounds below his waist, irrespective of health conditions, he attended the Casablanca Conference 1943 and the notable development at the conference was the finalisation of Axis force towards unconditional surrender.

In the Teheran conference 1943 FDR outlined his vision of United Nations dominated by four police men (The United States, Britain, China, and the Soviet Union), who would have the power to deal immediately with any threat to the piece and any sudden emergency which require action. As not have faith in majority, VETO power to individual police man were suggested. The Yalta Conference took place in a Crimean resort town and by the time the war was at a close.

FDR’s last address on March 1,1945 to Congress on the Yalta Conference and the extract:

“I hope that you will pardon me for this unusual posture of sitting down during the presentation of what to say, but I know that you will realise that it makes it a lot easier for me not to have to carry about ten pounds of steel around on the bottom of my legs and also because of the fact that I have just completed a fourteen thousand mile trip.

“First of all, I want to say, it is good to be home. …….

“I am confident that the congress and the American people will accept the results of a permanent structure of peace upon which we can build, under God, that better world in which our children and grandchildren- your and mine, the children and grandchildren of the whole world – must live and can live.”

Early in April 1945 FDR travelled to his cottage in Warm Springs, Georgia and had his last breath on April 12, 1945.

I am proud to be an INDIAN and also the citizen of UNITED NATIONS.

All the members of 193 member states publics are proud of their country and also the citizen of UNITED NATIONS. This Bonafede certificate issued on mutual trust is valid in a war free world.

On this day, April 12, every year we should pay tribute to our UNIVERSAL LEADER, FDR, and pray for the ever valid Bonafede Certificate.

Honestly UNITED NATIONS should come forward to celebrate January First the FOUNDER DAY and honour the late American President FRANKLIN DELANO. ROOSEVELT, the FOUNDER OF UNITED NATIONS, the glorious history for the coming generation.

JANUARY FIRST THE FOUNDER DAY OF UNITED NATIONS

LATE AMERICAN PRESIDENT FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT FOUNDER OF UNITED NATIONS

This is my dream, when my dream come true.

JAI HIND