|

In April 1933, at the beginning of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first term, Undersecretary of State William Phillips called Labor Secretary Frances Perkins on the phone, expecting to tell her how immigration policy would work in the new administration. Philips “was almost blown off his end of the telephone.” Perkins told him “in no uncertain terms” that accepting immigrants whose lives were in danger was an American tradition and that “it was up to her department, not the State Department, to decide whether such admission would adversely affect the economic conditions or entail a fight with the AFL [American Federation of Labor].”1

As the first woman cabinet secretary and longest-serving Labor Secretary in American history, Perkins is best remembered as a key architect of the New Deal and Social Security. A lesser-known component of her tenure is her role in U.S. immigration policy, which was largely under her department’s control in the 1930s. From her volunteer work in a Chicago settlement house to her work on industrial safety in the wake of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, immigration issues had always been a part of Perkins’ labor activism. In many ways, if you were looking to flee Europe in the 1930s, she may have seemed like the ideal cabinet secretary to oversee immigration to the United States. Yet when she joined the cabinet, the United States did not even have an official definition of refugee, let alone a coherent policy for managing their petitions for entrance to the country.2

As the first woman cabinet secretary and longest-serving Labor Secretary in American history, Perkins is best remembered as a key architect of the New Deal and Social Security. A lesser-known component of her tenure is her role in U.S. immigration policy, which was largely under her department’s control in the 1930s. From her volunteer work in a Chicago settlement house to her work on industrial safety in the wake of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, immigration issues had always been a part of Perkins’ labor activism. In many ways, if you were looking to flee Europe in the 1930s, she may have seemed like the ideal cabinet secretary to oversee immigration to the United States. Yet when she joined the cabinet, the United States did not even have an official definition of refugee, let alone a coherent policy for managing their petitions for entrance to the country.2

Understanding the story of Perkins’ attempt to carve a welcoming refugee policy out of scraps of existing law, from her phone call with Phillips to the complete transfer of INS out of her control in 1940, requires us to follow a series of bureaucratic maneuvers between and among cabinet departments.3 But these maneuvers—and the smaller battles over bureaucratic turf that both precipitated and followed them—were part of fighting a greater war for the spirit and implementation of the nation’s immigration policy. Would the United States cling to its legally-codified hostility towards immigrants—even refugees—or would it open its doors to those fleeing persecution and violence? Perkins’ struggle to open those doors in the 1930s shows us how a culture war can be fought through, and consciously disguised by, bureaucratic battles over policy and implementation.

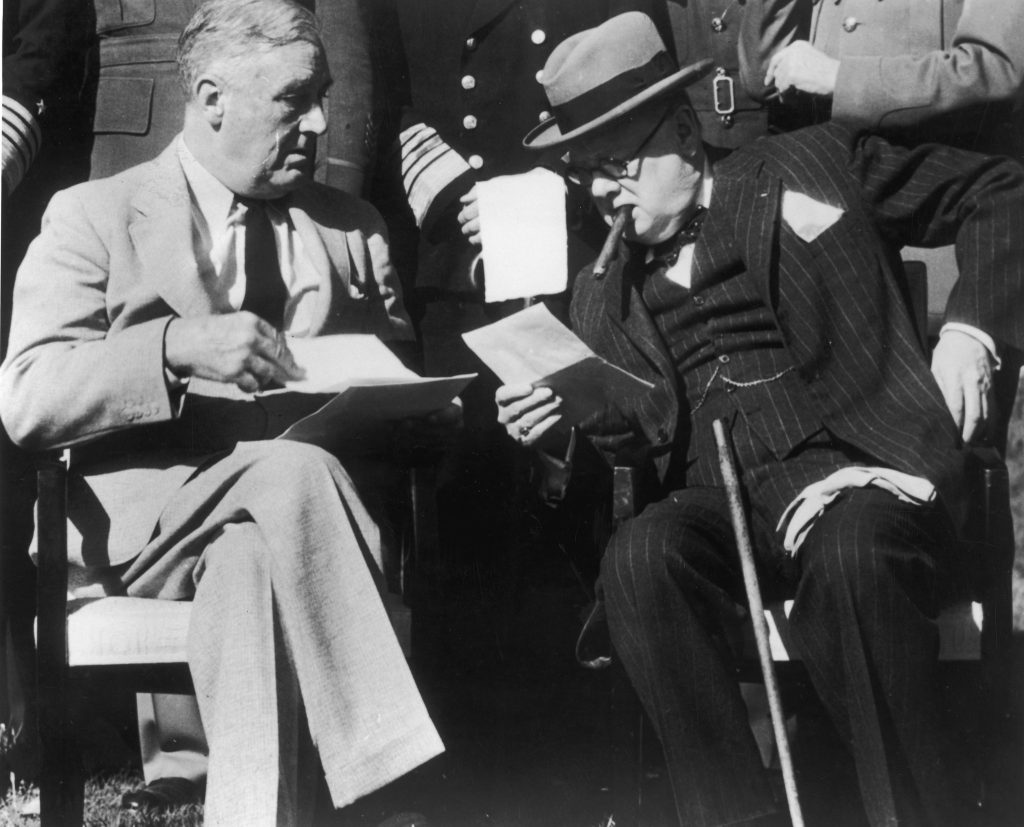

Barely a month before FDR’s inauguration on March 4, 1933, Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Americans had followed Hitler’s rise to power in the news, and now they followed the deteriorating status of Jewish Germans. In March 1933, Nazis smashed windows of Jewish stores, broke streetcars, and assaulted Jewish passersby. The following month, they boycotted Jewish businesses. In mid-April, FDR’s Cabinet convened to discuss a sudden surge in applications for immigration visas from Jewish Germans.4

At this time, immigration to the U.S. was guided by…

Read more at: