Adlai & Eleanor:

Progressives Who Shaped the World

by C. Stephen Heard, Jr.

It’s one of the great ironies of history that Franklin Delano Roosevelt died in April 1945, less than a month before the Allied victory over Nazi Germany. Despite FDR’s strong leadership and immeasurable contributions to that success, his ultimate but unrealized dream was to participate in the creation of a new world body that would bring nations together to build a lasting peace. That dream could well have died with him in the devastated aftermath of the Second World War. Instead the United Nations was brought to life in 1945 by the selfless, dedicated work of many people, but perhaps most importantly by the tireless efforts and contributions of two gifted individuals who became political allies and close friends, the President’s widow, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Adlai Stevenson.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s public service background particularly her selfless, decades long efforts as “the President’s eyes and ears” is generally well known to the American public. However, it was her important post-war efforts that perhaps gave her the most pleasure, particularly her work in the foundation and development of the United Nations, as well as what became a close personal friendship – indeed an alliance – with Adlai Stevenson. In fact, by 1948 their relationship had developed to the point that Mrs. Roosevelt played a key role in convincing Mr. Stevenson to run for Governor of Illinois and later to twice seek the Democratic Party’s Presidential nomination – in 1952 and 1956.

Like Mrs. Roosevelt, Adlai Stevenson was the product of a wealthy, well connected and politically active family. Mr. Stevenson’s maternal great grandfather, Republican Jesse Fell, had been a close friend of Abraham Lincoln and served as the future President’s campaign manager in 1858. His paternal grandfather and namesake had been vice president during Democrat Grover Cleveland’s second term. In 1900 the elder Stevenson again ran for vice president with the renowned orator, William Jennings Bryan, this time unsuccessfully. In that same year, Adlai Stevenson II was born.

Young Stevenson attended Choate, a well-regarded boarding school in Connecticut, and then Princeton University, editing the undergraduate newspapers at both schools. He attended Harvard Law briefly, but found his studies “uninteresting.” After failing several classes, he withdrew. He returned to his Bloomington, Illinois home, and began working for the family-owned newspaper, The Daily Pantagraph, which has been founded by his grandfather and was the source of much of the family wealth. After a chance meeting with Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, his interest in the law was rekindled. Stevenson entered Northwestern University and eventually became a lawyer practicing law in Chicago. In 1928 he had married – and 20 years later divorced – Ellen Borden, a wealthy socialite who gave him three sons he adored: Adlai III, Borden and John Fell.

In 1933, Stevenson was one of the bright, young lawyers who emigrated to Washington to participate in the newly elected president’s efforts in structuring what became known as the New Deal, designed to bring America out of the Great Depression. Stevenson’s first two years in the Capitol were spent as Special Counsel to the recently formed Agricultural Adjustment Administration organized to help the country’s struggling farmers. After two years, Mr. Stevenson returned to Chicago to practice law. His strong interest in America’s future led him to serve a one-year term as president of the Chicago Counsel of Foreign Relations. He also became the Chicago chairman of the William Allen White Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies. At the start of World War II, Mr. Stevenson returned to Washington to serve as Special Assistant to President Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox. In 1945, then Secretary of State, Edward Stettinius, appointed Mr. Stevenson as Special Assistant to Assistant Secretary of State Archibald MacLeish to work on the establishment of the United Nations.

Upon President Roosevelt’s death in April, vice president Harry Truman became his successor and soon invited Mrs. Roosevelt to join the U.S. delegation at the first meeting of the United Nations General Assembly to be held in February, 1946 in London. Mr. Stevenson also became an early participant in the organization of the UN – attending the new institution’s first organizational meeting in San Francisco in 1945. He later played a key-role in the workings of a “preparatory commission” which met in London in the fall of 1945 and early 1946. Mr. Stevenson’s early involvement with the UN is important to understanding his lifetime commitment to his country’s position in a changing and increasingly dangerous world.

On September 4, 1945 Mr. Stevenson sailed for England to assume an important role in the organization’s first organizational meetings. Adlai Stevenson was in impressive company – Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, Former Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, and Charles “Chip” Bohlen, the State Department’s Russian expert who had served as President Roosevelt’s translator at the Yalta and Potsdam conferences. In the fall of 1945, however, he spent a good deal of time with Mr. Stevenson on the voyage across the Atlantic discussing U.S. – Soviet relations. Bohlen was deeply impressed by his new colleague, especially by “the freshness and sensitivity of his mind and his civilized approach to world problems”.

Mr. Stevenson’s work at the New World body after his organizing efforts was initially devoted during the U.N.’s first General Assembly in early 1946, helping to pass its first 103 resolutions. During the formative period in London, Mr. Stevenson began to know Mrs. Roosevelt, first at evening social events, then professionally during the General Assembly’s second session in October, 1946. As Mr. Stevenson noted in his diary on October 2nd:

“[we] discussed politics, languages, and education. Everything confirms [my] convictions that she is one of the few really great people to have known.”

Despite their evolving bond, they sometimes underwent lengthy periods out of touch with each other due to their respective schedules and commitments. For example, one of Mrs. Roosevelt’s most demanding efforts was her position as a Chairlady of the U.N. Commission on Human Rights, which she held for several years. From the perspective she gained from working together, Mrs. Roosevelt believed Mr. Stevenson possessed the same qualifications as her late husband…urbane, articulate and highly intelligent.

In 1947, Mrs. Roosevelt encouraged Mr. Stevenson to run for Governor of Illinois. Once again, Mr. Stevenson chose public service over his law practice. Stevenson was also the chosen candidate of Jacob Avery, the leader of the powerful Chicago Democratic political organization. His opponent was incumbent Republican Dwight Green who had presided over a state administration that was widely viewed as corrupt. Mr. Stevenson upset Green by 572,067 votes, a record margin over all previous gubernatorial elections in Illinois.

Governor Stevenson’s “clean-up” administration was highly effective and propelled him to national recognition among Democrats. As noted in the papers of Eleanor Roosevelt –

“He attacked political corruption in the state…reorganized the Illinois government, improved infrastructure, fought organized crime and drew additional [national] attention when he resoundingly vetoed the Broyles loyalty ‘oath bill’.”

During his four-year term (1948-1952), Mr. Stevenson called “Gov” by many, demonstrated his very unique sense of humor. When the Illinois legislature passed a bill dealing with roaming cats declaring they were a public nuisance, Governor Stevenson vetoed the bill and publicly stated:

“It is in the nature of cats to do a certain amount of un-escorted roaming, the problem of cat versus bird is as old as time. If we attempt to solve it by legislation who knows but what we will be called upon to take sides in the age old problem of dog versus cat, bird versus bird or even bird versus worm. In my opinion, the state of Illinois and its local governing leaders already have enough to do without trying to control feline delinquency. For these reasons, and not because I love birds the less or cats the more, I veto and withhold my approval from Senate Bill Nol. 931.”

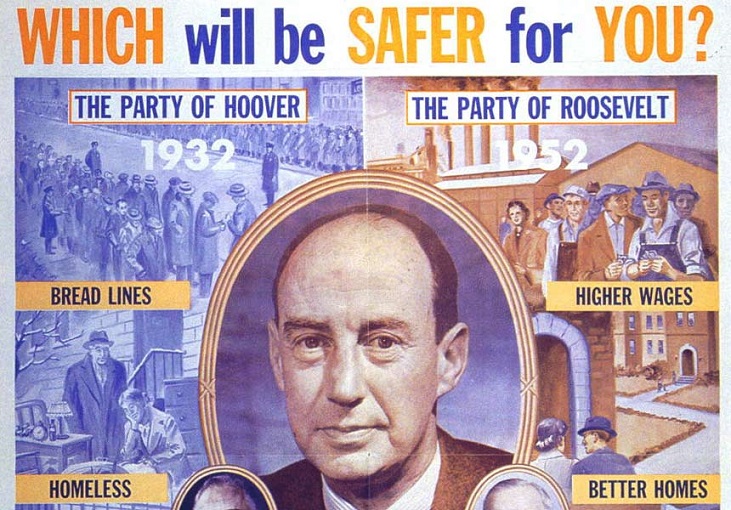

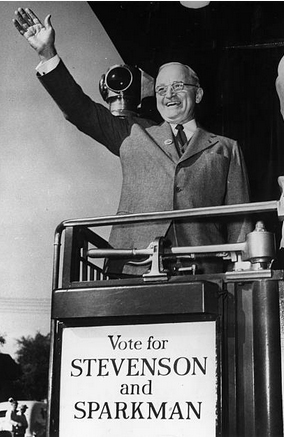

Stevenson’s strong term as governor, together with his intelligent and engaging speaking skills, had generated a national following. In early 1952, while Governor Stevenson was still in office, President Truman announced he would not seek the Democratic Presidential nomination in 1952. Mrs. Roosevelt urged Governor Stevenson to run for the nomination. President Truman, after considering several other potential candidates, met with Mr. Stevenson in Washington and suggested the soon to be ex-Governor run with his support. A “draft Stevenson” movement had begun in the spring of 1952 led by friends like George Ball, a banker and eventual long time diplomat. Ball would later write of Stevenson –

“He lighted up the sky like a flaming arrow, lifting political discussion to a level of literacy, eloquence, candor and honor that tapped unsuspected responses in the American electorate.”

But it was his friend and political soulmate, Eleanor Roosevelt that in looking back put the Governor’s candidacy in bold perspective.

“In 1952, it was my opinion that Governor Stevenson would probably make one of the best Presidents’ we ever had.”

Stevenson, however, continued to insist into the summer of 1952 that he intended to run for re-election as Governor of Illinois and “no other office.” The pro-Stevenson sentiment within the Democratic Party carried the day and in late July the Governor of Illinois was nominated to run against President Eisenhower in the fall. He had not run in any State primaries. Accordingly, the well-respected New York Times columnist Arthur Kroch told Mr. Stevenson “I think you may be one of the true drafts in our political history.”

Mrs. Roosevelt acknowledged after the fact that Governor Stevenson’s victory was virtually impossible due to the American public’s hero worship of General Eisenhower who represented “Victory in Europe.” Although he was beaten badly by the General in the 1952 election, Stevenson pulled 3 million more votes than President Truman had over his Republican opponent, Thomas Dewey, in 1948. Governor Stevenson never came even close to losing his sense of humor. When the powerful Connecticut Republican Stewart Alsop called him an “egg head” based on his baldness and his intellectual, academic air, Stevenson joked “Eggheads of the world, unite. You have nothing to lose but your yolks.” Following another speech in the 1952 campaign, a lady came up to him and offered:

“Oh, Mr. Stevenson, your speech was positively superfluous.” To which he replied, “Thank you madam, I’ve been thinking about having it published posthumously.” “Oh, that will be nice. The sooner the better.”

Impervious to defeat, in 1953 Stevenson undertook an ambitious but exhausting world trip, reminiscent of Wendell Willkie’s One World journey after losing the 1940 election to President Roosevelt. Mr. Stevenson traveled through Asia, the Middle East and Europe. Stevenson arguably enjoyed a greater success than Willkie, because he spent a considerable amount of his time listening to the ordinary people of the countries he visited. Listening was one of Ambassador Stevenson’s greatest attributes. On the world stage democracy faced an enormous and threatening challenge from the rise of communism in the 1950’s. Stevenson, always listening, talked of America’s strengths and the future promise the United States offered for the world. He almost always spoke to large crowds of cheering ordinary citizens of the countries he visited. Upon his return, Stevenson, although exhausted, told a group of his supporters “we carried all of Asia”. He also spoke to many leaders with persuasive yet diplomatic understanding of the delicate position they were in at the time due to the largely forgotten struggle between democracy and communism in the 1950’s.

Notwithstanding his 1952 loss to Eisenhower, Mr. Stevenson and Eleanor Roosevelt essentially became the inspirational – if not the de facto – leaders of the Democratic Party in the 1950’s. It seems Stevenson felt that he needed to share his world view — perhaps to strengthen a potential run against President Eisenhower in 1956. In any event, he campaigned vigorously for the party’s candidates in the 1954 mid-term elections despite having undergone kidney surgery in April of that year. On the campaign trail, he hammered three issues which strongly resound in today’s politics: foreign policy, the domestic economy and internal security. Ambassador Stevenson’s leadership and hard work produced Democratic majorities in both the House and Senate, as well as 9 new governorships. He also was able to wipe out his party’s $800,000 debt – a significant amount at the time. His party leadership in 1954 certainly helped and appeared to assure his nomination two years later.

The two friends didn’t always agree however. In May of 1954 the United States Supreme Court handed down a unanimous landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education arising out of segregation in the public school system of Topeka, Kansas. The Court’s opinion held the “separate but equal” doctrine the Court had established in 1886 was unconstitutional. Mrs. Roosevelt was one of the country’s strongest advocates for civil rights. In 1945, she had accepted an invitation to serve on the Board of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (“the NAACP”) and was elected the co-chair of the organization. When the NAACP moved for defunding non-compliant school districts, Mr. Stevenson took a significantly different approach urging “gradual implementation of the Court’s decision.” His position was regarded as less than satisfactory for the Democratic Party’s liberal standard bearer. Despite the Governor’s strong commitment to minority rights throughout his career, some thought Stevenson’s muted reaction was influenced by his view that a strong negative response to the Court’s decision in the Southern States could lead to the breakup of the Democratic Party. Fortunately, Stevenson’s tepid stance and mild estrangement from Mrs. Roosevelt was short lived. On her forthcoming birthday he wrote her:

“Personally, I am not sure we should celebrate your birthday or that we should be reminded that time passes for you as for the rest of us. There are some people for whom time seems to stand still and who can bridge all the generations by their interval on earth, but they are very rare. You are one, and for me, you will always be the same age, and no age”.

While Stevenson and Mrs. Roosevelt were invigorating the Democratic Party, a junior Senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, was leading a well-publicized campaign to rid the Federal Government and American society of so-called “subversives” or “communists”. Mr. Stevenson regarded McCarthy’s reckless statements and actions as highly corrosive and irresponsible both in the United States and abroad. Accordingly, Stevenson attacked McCarthy’s vitriol with what many regarded and supported as uncharacteristically strong force while President Eisenhower again remained relatively silent and “above the fray” — presumably thinking that McCarthy’s nasty program would help the Republican cause. But “McCarthyism” finally was censored by the House of Representatives in December, 1964 although its hateful activities would linger.

In 1956 Mr. Stevenson was again his party’s nominee to run against President Eisenhower’s pursuit of a second term. Eisenhower, notwithstanding the President’s preoccupation with the Soviet Union and the intensifying Cold War, won reelection by an even larger margin than he had in 1952. Mr. Stevenson had clearly, once again, not lost any of his trademark sense of humor when he responded to reporters: “The President was so far ahead of me that I was lucky to come in second.”

Despite two successive presidential losses, Stevenson was initially interested in the possibility of a third attempt in 1960. While Mrs. Roosevelt initially supported him in the early days, his close friend eventually threw her considerable assistance to Massachusetts Senator, John F. Kennedy.

Despite two successive presidential losses, Stevenson was initially interested in the possibility of a third attempt in 1960. While Mrs. Roosevelt initially supported him in the early days, his close friend eventually threw her considerable assistance to Massachusetts Senator, John F. Kennedy.

After Jack Kennedy won the 1960 election, he felt he should offer Governor Stevenson a significant position in the new administration. Over the objections of his brother, Robert Kennedy, the President however offered Mr. Stevenson his choice of Attorney General, Secretary of State or Ambassador to the United Nations. Despite his earlier expression of a desire to be Secretary of State, Mr. Stevenson chose the United Nations position where he distinguished himself by diligently working on international cooperation while diplomatically maintaining America’s interests. President Kennedy assured his new Ambassador that he would play an important role in all major policy decisions, but that turned out not always to be the case.

After the 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco (about which Stevenson was not consulted), Soviet Premier Khrushchev offered to install nuclear missiles in Cuba. When American U-2 surveillance aircraft confirmed the expedited construction of missile launch sites and the presence of a quantity of intermediate range nuclear missiles in Cuba in October of 1962, President Kennedy ordered a naval blockade of the island. This time Ambassador Stevenson was fully informed and prepared. At an emergency meeting of the Security Council, Ambassador Stevenson forcefully asked the Soviet representative Valerian Zorin if Russia was installing missiles in Cuba, concluding with the now famous demand “Don’t wait for the translation, answer yes or no!” When Zorin appeared to refuse to answer the question, Stevenson strongly retorted: “Sir, I am prepared to wait for my answer until Hell freezes over.” Ambassador Stevenson then showed U-2 photographs that proved the existence of the missiles in Cuba. The Soviets reluctantly honored the blockade as several of their warships approached Cuban waters. The warships turned around rather than challenge the blockade. They went on to withdraw their missiles, preventing a nuclear confrontation.

Ambassador Stevenson’s exemplary statesmanship at the United Nations was followed by a succession of tragedies – the first coming immediately after the Cuban missile crisis. Eleanor Roosevelt died in November 1962 following multiple complications after being struck by a car while walking in Manhattan in November 1960. At her memorial service at the United Nations, Mr. Stevenson eulogized his beloved partner by sadly saying he had lost more than a friend, He had “lost an inspiration: for she would rather light candles than curse the darkness and her glow had warmed the world.” At the end of his heartfelt and moving words he quoted a phrase used years before by President Truman: “the passing of this great and gallant human being who was called ‘The First Lady of the World’.”

The death of Eleanor Roosevelt was followed a short year later by the shocking assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas in November 1963. Dallas had become what many called the “City of Hate” largely due to the anti-United Nations, anti-Washington vituperative bias generated by a far right group known as the John Birch Society headquartered in Dallas and founded by a retired Army General Edwin Walker.

Ambassador Stevenson was in Dallas at the time to speak about the United Nations. While he was used to the hostile crowds, one particular appearance was both beyond shocking as well as personally dangerous. Mr. Stevenson was shouted down and had to be escorted off the stage by Dallas policemen. In the riotous confusion a woman screamed at him “who elected you Adlai” and hit him over the head with a sign. When a policeman was getting ready to arrest the woman, Ambassador Stevenson calmly and with his characteristic grace said: “I don’t want her to go to jail; I want her to go to school!” Several days later, Mr. Stevenson was visiting his son, John Fell, in San Francisco and called the White House to warn the Secret Service that the atmosphere in Dallas was ugly, frightening and dangerous. He strongly advised the President’s advisors and the Secret Service that President Kennedy should forego the trip. The President went anyway, with tragic results.

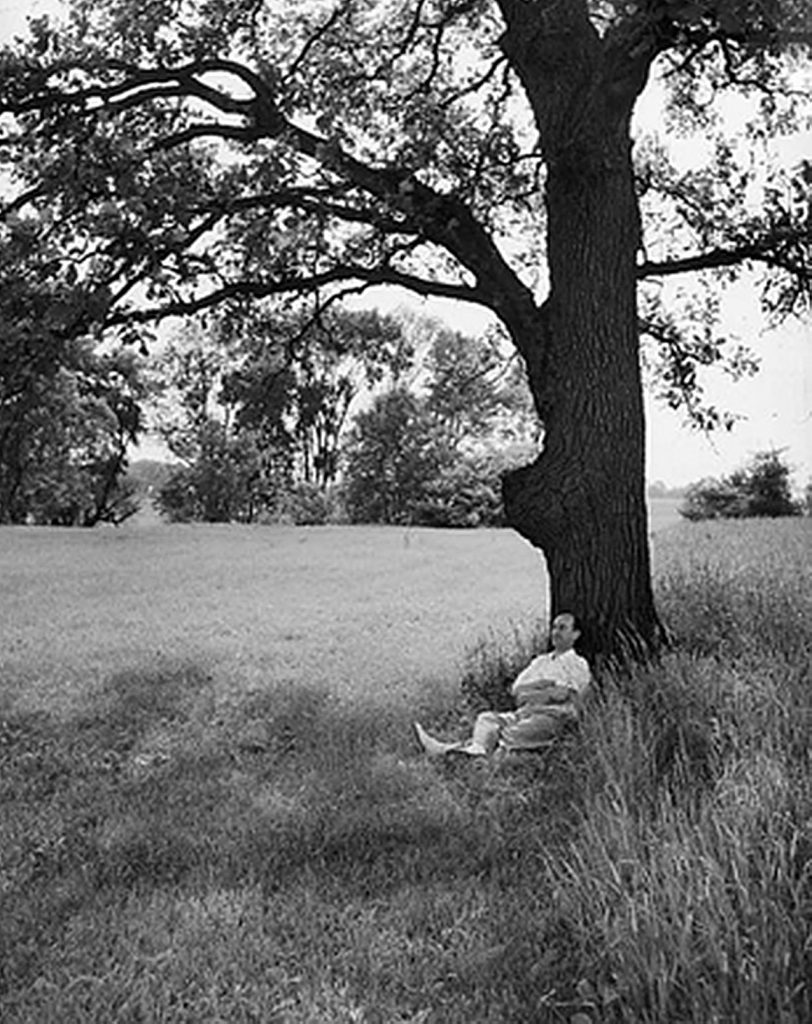

A little over a year later, America lost another of its greatest statesmen when Adlai Stevenson died of a massive heart attack while walking in London with his friend Marietta Tree. Only days before his death, the Ambassador had a long conversation with journalist Eric Sevareid at the US Embassy. They discussed Stevenson’s frustrations with Vietnam and other foreign entanglements. He told Sevareid that longed to resign, and return to his farm in Libertyville and “sit in the shade under that tree with a glass of wine in my hand and watch the people dance.”

Hopefully this great man has been joined under that tree by his equally great and dear friend, Eleanor Roosevelt, where they can watch the dancing together.