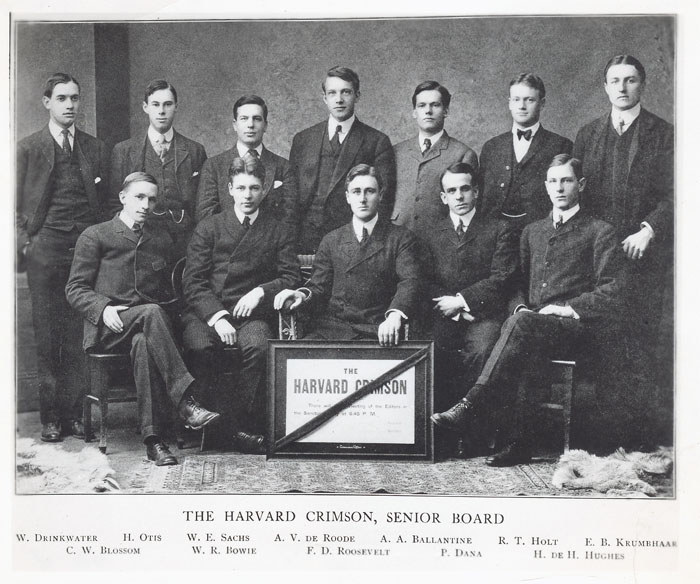

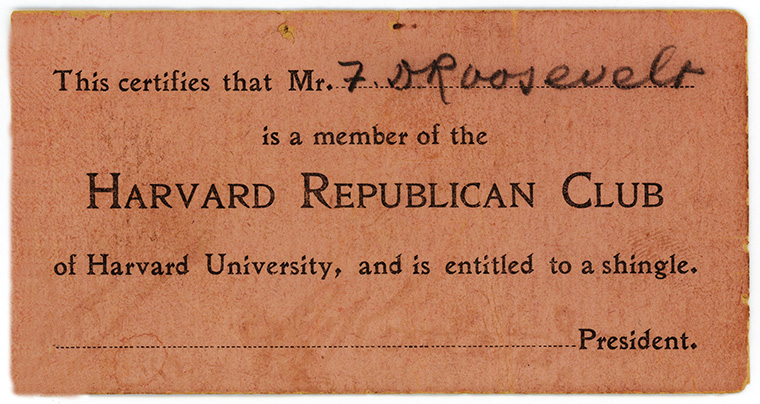

It seems almost impossible, but here it is, clear as day: F.D. Roosevelt, a member of the Harvard Republican Club! What could have happened? Have we moved into the realm of alternate history?

It seems almost impossible, but here it is, clear as day: F.D. Roosevelt, a member of the Harvard Republican Club! What could have happened? Have we moved into the realm of alternate history?

The answer, as it turns out, far more mundane and consists of a mere two letters: TR.

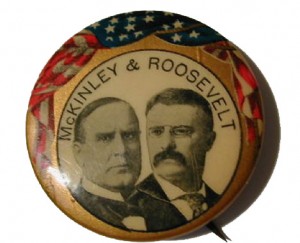

Although FDR’s father had traditionally voted Democratic (one of the few wealthy families in his district to do so), blood bonds proved stronger than political ones, and Father James, along with his son, loyally threw their support to the man FDR had idolized since a boy when he ran with McKinley in 1900.

FDR to Sara, October 31 1900

Last night there was a grand torch-light Republican Parade of Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. We wore red caps and gowns and marched by classes into Boston and through all the principal streets, about 8 miles in all. The crowds to see it were huge all along the route and we were dead tired at the end!

This fascinating little bit of ephemera – most likely dating from FDR’s freshman year – came to me via author Geoffrey Ward, who’s preparing the companion volume to the new Ken Burns film on the Roosevelts, and who’ll be our speaker next April. Geoff had written to inquire whether or not I knew anything about the mysterious “shingle” referred to on the card. I could certainly guess the context: the term “hang out one’s shingle” still has some meaning today, but I couldn’t quite figure out what it referred to in this context. Then by chance, we acquired a new book, Harvard College by an Oxonian, published in 1894. It contains the most interesting passage:

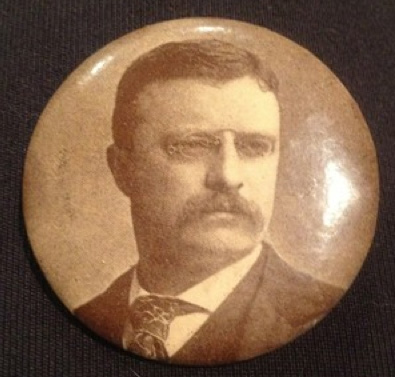

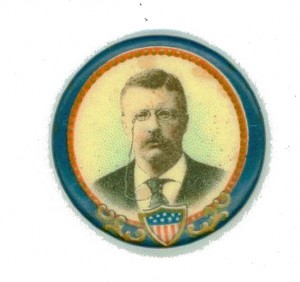

Another of our recently purchased TR buttons. This one FDR might have acquired at Groton when TR passed through, campaigning for McKinley in the fall of 1900. McKinley was assassinated on September 6, 1901, and “Cousin Ted” became president.

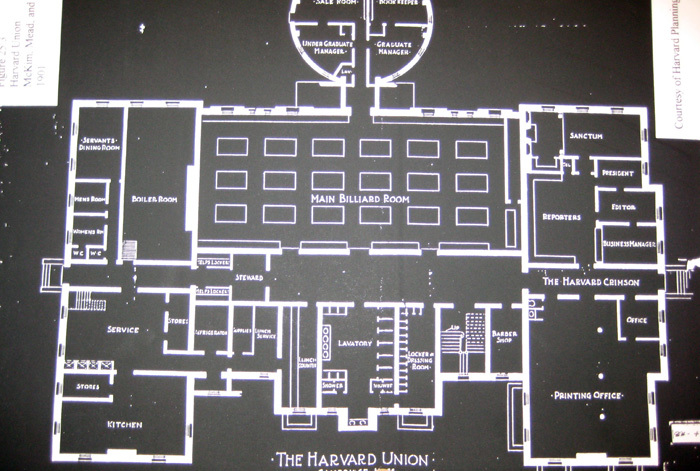

“The rooms we visited in Hastings were on the top floor. They were pleasant and comfortable — very like the rooms in one of our Colleges, only the bedchamber was far better. There was the wide window-seat with its red cushions and out-look over the tops of the graceful American elms. Above the two doors of the sitting-room were hanging one or two printed notices, which had been appropriated or misappropriated by some means or other. It is the pride of a Freshman to have his walls adorned with signs and ” shingles ” which he has ” ragged.” [stolen] An oblong piece of wood called a shingle takes the place in America of the brass plate on the outside door. It is not fastened to the door, but is hung near it on the wall. These shingles, and in fact all kinds of announcements and notices, the adventurous Freshman delights to carry off, surveying his room with just pride, when he sees on the walls such inscriptions as : ” Jones & Co., Civil, Sanitary, and Landscape Engineers”; “Thomas Smith, M.D., Office Hours 2-4; 7-9 ” ; ” Hair-dressing and Complexion Parlors ” ; ” Under- takers. Locker’s Casket Warehouse ” ; ” The College Dining Rooms and Ice Cream Parlors.” These trophies correspond to the door-knockers which have been known to adorn the rooms of a Christ Church undergraduate. One kind of shingles is won by easier, but, perhaps, no less glorious means, ” Peace hath her victories no less renowned than war.” Harvard abounds in clubs, and each club has its own shingle.

Ah ha! Mystery solved! Or, at least, the bit about the shingle. But what of the larger question: how did FDR go from Democrat to Republican and back to Democrat again? According to Ward in his monumental A First Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the move had little to do with political convictions: “… as early as his sophomore year at Harvard, Franklin had evidently decided to become a Democrat. His reasoning was crisp and pragmatic. The Republican Party was filled with young members of the family whose claims to the President’s mantle were more plausible than his. Only as Democrat could a Roosevelt from outside Sagamore Hill hope to rise very high – and Franklin Roosevelt would never willingly settle for less.”

Ah ha! Mystery solved! Or, at least, the bit about the shingle. But what of the larger question: how did FDR go from Democrat to Republican and back to Democrat again? According to Ward in his monumental A First Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the move had little to do with political convictions: “… as early as his sophomore year at Harvard, Franklin had evidently decided to become a Democrat. His reasoning was crisp and pragmatic. The Republican Party was filled with young members of the family whose claims to the President’s mantle were more plausible than his. Only as Democrat could a Roosevelt from outside Sagamore Hill hope to rise very high – and Franklin Roosevelt would never willingly settle for less.”

Simply put: there were already too many Roosevelts on the other side (TR alone had four sons), and FDR wanted to be the biggest fish in the smaller pond.

No burning passion (except perhaps that of self-advancement), no huge sense of mission. Just cold pragmatic calculation: where best can I shine?

Some of FDR’s more altruistic friends were appalled…

Interesting to ponder the alternate history if FDR hadn‘t decided to switch back…. Just another Republican Roosevelt among the pack. Some more progressive, some less, but no standouts. A term of two in Congress perhaps. Certainly no hardened politician to propose the New Deal. No wise, steady hand at the helm during WWII. Almost as fascinating to contemplate as another little-known historical what-if: Hoover, who in 1920 had yet to declare a party affiliation after his lauded service in WWI, seriously considered running as the Democratic candidate with FDR as his running mate. Hugely popular after his successes in Europe clothing and housing refugees, Hoover might very well have won. Imagine: without the laissez-faire economics of Coolidge and Harding, there’s no run-up to the stock market crash; no crash at all in fact, just a regular recession, which FDR, now president after Hoover’s two terms, inherits. His unpopularity soars, and the Big-stick Republicans return to power in 1932, their bellicose worldview matched by the rise of fascism. We enter WWII in 1939, before we were truly prepared to fight, with disastrous results. Germany dominates Europe, England and Russia are reduced to smoldering ashes – it’s Churchill not Hitler who dies in his bunker – and Imperial Japan dominates a newly formed Empire in the East. The US, hounded on all sides, beaten and bankrupt, surrenders, loses Alaska and Hawaii as well as all its overseas territories, and is reduced to a third-rate power…

Hmmm… all that from a tiny switch in party affiliation… Remarkable how seemingly mundane actions create a nexus in time that alters everything that comes after!

Ah well, no more time to ponder alternate histories: I must track down one of these shingles for the Suite!