When Reason Trumped Politics:

The Remarkable Political Partnership of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Wendell L. Willkie

by C. Stephen Heard, Jr.

As the American people nervously watch this year’s presidential campaign descend into a rant of name calling and outright crudity that would be inappropriate in a saloon, it might be wise to pause and look back 75 years to a remarkable partnership between Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Wendell L. Willkie, opposing candidates in the 1940 election. Though the race was boisterous and equally contentious — FDR was running for an unprecedented third term to the horror of the Republican Party — each candidate managed to wage a vigorous campaign that kept sight of a shared common goal: the betterment of America. Even more importantly, their cooperation during that election year and in the years that followed likely prevented the collapse of Great Britain and provided America with its greatest fighting ally against the forces of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

This relationship is all the more remarkable considering the very different starting points of these two men. FDR was born to an affluent family in Hyde Park, New York. He graduated from two of the country’s most prestigious schools, Groton and Harvard. (He attended Columbia Law as well, but never completed his degree.) Intrigued by politics at an early age, Roosevelt was elected to the New York Senate in 1910, and later, despite the crippling effects of the polio he contracted in 1921, he achieved the governorship of New York in 1928. Roosevelt owed his allegiance to the Democratic Party as much to sympathy with its tenets as to the fact that his distant cousin Theodore Roosevelt had four sons who appeared eager to enter politics. FDR realized very early on that there would be much more opportunity with the Democrats than there would ever be in the Grand Old Party.

Wendell Willkie

Willkie, on the other hand, was born to a modest family in 1892 in the small Indiana town of Elwood and attended both college and Law School at Indiana State University. His interest in politics literally began when he was barely four years old — his father took him to a torchlight procession for the Democratic Presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan, who had come to Elwood during the 1896 campaign. His commitment to politics continued through his school career including meeting with the liberal trial lawyer, Clarence Darrow. Willkie also developed an interest in communism reading Karl Marx and even considered a run for Congress.

On April 2, 1917, the same day Woodrow Wilson signed a declaration of war against Germany, Willkie volunteered for the United States Army. He was sent to France but the war ended before he saw combat. In 1918, he married Edith Wilk, a librarian from Rushville, Indiana. Soon his mother, Henrietta, herself a lawyer and one of the first women admitted to the Indiana bar, convinced Willkie that his strong character and intelligence would better serve him in a larger arena. So the young couple moved to Akron, Ohio where Willkie started with Firestone Tire and Rubber, and soon joined a local law firm. He soon became a leading utilities lawyer and was elected President of the Akron Bar Association.

His wife, Edith, who shared the same ambitions as her mother-in-law, convinced her husband to move to New York where he joined a major utility company, Commonwealth and Southern Corporation, as General Counsel. In 1933 Willkie became the president of C&S, which through multiple acquisitions, had become the largest public utility holding company in America. Maintaining his interest in politics, Willkie became a delegate to the 1932 Democratic Convention. He eventually supported Roosevelt as the party’s nominee and contributed $150 to his campaign.

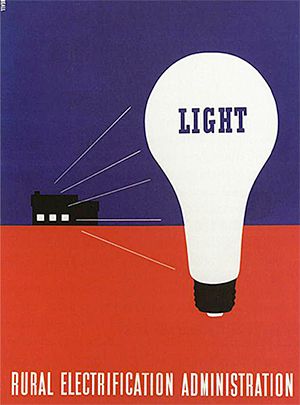

REA Poster 1939

The two men became adversaries as the respective spokesmen for the opposing sides in one of America’s key issues in the 1930’s – the expansion of the country’s electrical grid. Willkie felt strongly that private utilities, like C&S, could and should do the development job. Because of the project’s scale, Roosevelt felt equally strongly that this was a job best undertaken by the Federal government

Although Thomas Edison had developed the electrical means to power the incandescent light bulb in 1870, by the 1930’s only the northeast surrounding New York and the northern Midwest around Chicago had enjoyed the benefits of the new power source. Virtually the entire Midwest and southern areas of the country were without electricity. The long power lines and generation facilities required to electrify these massive land areas crucial to America’s farms and agricultural areas were simply too extensive and too expensive to finance privately. Roosevelt therefore introduced and engineered legislation through a Congress he knew was deeply aware of the broad and painful impact the Depression was having on their constituents. Roosevelt’s leadership led to the creation of the Rural Electrification Administration(all external links in this article are to wikipedia.org unless noted), the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Public Utilities Holding Company Act. Through the legislative hearing process, as well in speeches and the press, the two men vigorously defended their differing approaches, yet in stark contrast to today, publicly expressed respect for their opponent.

Willkie’s first meeting with Roosevelt was in the White House in December 1934. After a cordial exchange, Willkie sent a telegram to his wife “CHARM OVERRATED. I DIDN’T TELL HIM WHAT YOU THINK OF HIM.”

As Willkie’s potential appeal grew in the eyes of the Republican leadership, they seemed to be unmindful, at least at first, of his liberal and internationalist views, concentrating instead on Willkie’s increasingly vocal objections to the anti-business direction of the Democratic party. In fact, he broke ranks and voted for Al Landon in the 1936 election.

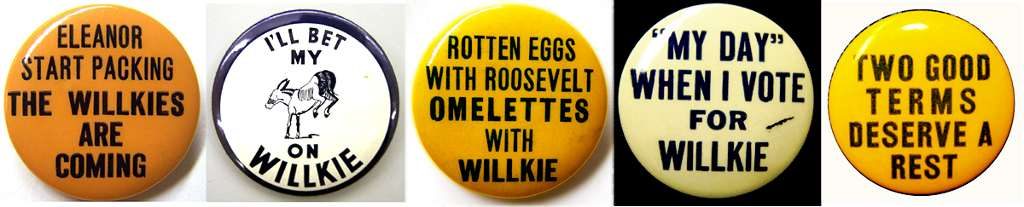

In 1939, feeling that the Democratic party had abandoned him, Willkie switched his voter registration from Democratic to Republican at the suggestion of prominent New York Republican businessmen who planned to back him as the candidate best qualified to run against President Roosevelt in 1940. Willkie won the Republican nomination on the sixth ballot at a brokered convention. He then proceeded to wage a vigorous and at times aggressively personal campaign against the president, largely centered on domestic issues. In particular, Willkie objected to FDR’s decision to run for an unheard of third term, viewing it as a highly dangerous precedent. “If one man is indispensable,” he argued, “then none of us is free.” However, on the international front, Willkie spoke often about the dangers facing America, and believed, as did Roosevelt, in the need to help our allies, especially Great Britain. He supported, for instance, Roosevelt’s call for the first ever peacetime draft, as well as the Destroyers for Bases Agreement — policies that had limited appeal within the isolationist ranks of the Republican party — but that Willkie felt were essential to the security of the United States.

Some hardly subtle Willkie campaign buttons from the collection at the FDR Library and Presidential Museum

In the end, with active wars raging in Europe and the Far East, the electorate decided not to change leadership. Roosevelt won the election easily, capturing both the popular and Electoral College vote by very large margins.

Interestingly at the time, there was a precedent for Roosevelt reaching out to Republicans in his desire to build a bipartisan foreign policy. In the spring of 1940, the president had a growing and increasingly deep concern as he watched country after country in Europe falling under Hitler’s war machine. Roosevelt also had the personal and political strength to take a bold step especially given the strong desire to stay out of the war by Republican isolationists. He brought two prominent Republicans, Henry L. Stimson and Frank Knox into the government as his Secretaries of War and the Navy, respectively. Both men had vigorously opposed Roosevelt’s 1930 campaign seeking reelection as the governor of New York. Both men, however, went on to be strong and highly regarded supporters of Roosevelt’s wartime strategies and actions. In that long-ago time the differences between the parties — with the exception of the Republican right-wing isolationists — was significantly closer than it is today.

The success of Roosevelt’s decision to bring two well-known Republicans into his cabinet as well as his respect for Willkie, whom he had just defeated, brought about a unique and uncommon phenomenon historically unheard of in Presidential elections. Shortly after the November election President Roosevelt told close advisors that he wanted to use his former adversary’s talents and intelligence, perhaps even offer Willkie a position in the government. The opportunity presented itself before the end of the year.

On December 29, while the president was trying to relax in the Caribbean, he received an urgent message from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the effect that England was running out of cash and thus unable to buy arms and take other steps to protect the British people. Roosevelt’s response was characteristically swift and strong.

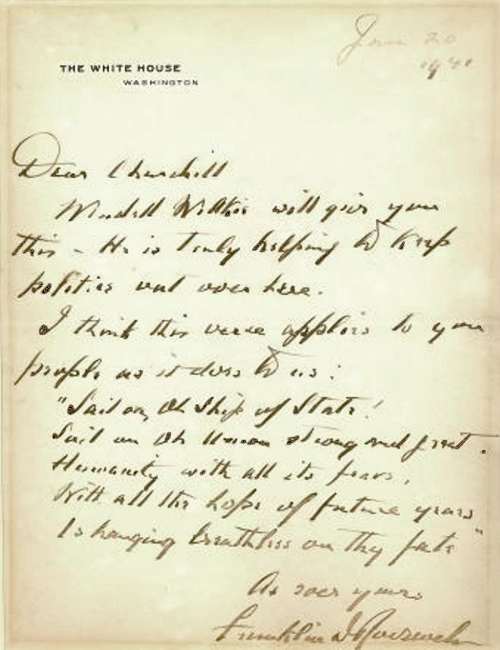

The original letter from Roosevelt hung for many years on the wall at Chartwell.

In January 1941, the president asked Willkie to go to London to personally deliver a letter to Mr. Churchill whom Mr. Roosevelt frequently addressed as “a former naval person.” In the letter, Roosevelt wrote, quoting from Longfellow:

January 20, 1941

Dear Churchill:

Wendell Willkie will give you this –He is truly helping to keep politics out over here.

I think this verse applies to you people as it does to us:

“Sail on, Oh Ship of State!

Sail on, oh Union strong and great.

Humanity with all its fears

With all the hope of future years

Is hanging breathless on thy fate.”

As ever yours,

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Churchill was inspired by the letter and later gave one of his most memorable speeches in Parliament: “Give us the tools, and we will finish the job,” he finished. (You can listen to the relevant excerpt HERE (link to youtube.com) Churchill framed the president’s letter and hung it at his private residence at Chartwell where it remained until his death.

Willkie had planned to visit embattled Britain on his own before Roosevelt asked him on the eve of his third inauguration to be the president’s informal emissary. Willkie accepted immediately. While he was in London, Willkie walked the streets without a helmet or gas mask, protections which virtually all Londoners carried because of constant German air raids. He visited bombed out sites and slept in air raid shelters and subways with British civilians. He also visited other cities and towns — Birmingham, Coventry, Manchester and Liverpool. Churchill invited him to 10 Downing Street, though he did insist on providing his guest with a helmet and gas mask.

On February 5, Roosevelt called Willkie to return to the United States to testify before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in support of the Lend-Lease legislation, which ultimately brought America into the war and helped turn the tide for the Allies against Hitler. Lend-Lease allowed the United States to supply food, oil, armaments, including warships and warplanes to Britain and other allies, including Free France, Britain, China.

Willkie and Churchill in front of Number 10

When ultraconservative Senator Nye of North Dakota asked Willkie at the Senate hearing about the apparent contradiction between his support of Lend-Lease and his previous campaign statements that Roosevelt would lead America into war by April 1, Willkie smiled and said, “That was a bit of campaign oratory, Senator.” The hearing room burst into laughter.

In his testimony, Willkie went on to explain, “I tried as hard as I could to defeat Franklin Roosevelt, and I tried not to pull any of my punches. He was elected president. He is my president now.”

Roosevelt, hoping to ensure public support for his controversial plan, conjured one of the most memorable metaphors of his time in office. Speaking to the press, he compared his plan to someone lending their neighbors a garden hose to put out a fire in their home. “What do I do in such a crisis?” the president asked the assembled reporters. “I don’t say …‘Neighbor, my garden hose cost me $15, you have to pay me $15 for it’…I don’t want $15 – I want my garden hose back after the fire is over.” To which skeptical Senator Robert Taft of Ohio later responded: “Lending war equipment is a good deal like lending chewing gum. You don’t want it back.”

Willkie’s testimony helped pass the Lend-Lease Act while earning him the enmity of the Republican Party.

Roosevelt’s respect for Willkie was again demonstrated in the summer of 1942. Specifically, the president’s former adversary, and now close advisor, suggested to Roosevelt that he again act as an envoy, to traverse the globe seeking insights into how the world could live in peace after the war. Travelling on an Army Air-Corps converted B-25 bomber with an Army Air-Forces crew, Willkie spent 49 days meeting with foreign leaders including Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union. General de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, British Field Marshall Montgomery in North Africa, Chang Kai-Shek in China and elsewhere showing American unity and discussing plans for the post war world.

Willkie greets General Chang Kai-Skek

Upon his return to the United States, Willkie reported to Roosevelt. He also authored a best-selling book, One World, with his observations and recommendations. The book sold one million copies in its first month. In October of 1942, Willkie made a radio “Report to the People” which was heard by about 26 million Americans. In his broadcast, Willkie urged that after the war America should join a world-wide organization, which ultimately became the United Nations. The President wanted Willkie to lead the new organization. Willkie declined.

In April, Willkie had joined a New York law firm which subsequently became one of the city’s largest and most respected, Willkie, Farr & Gallagher. Two months later he also represented Hollywood movie producers before a Senate subcommittee that was investigating claims that the industry was producing pro-war propaganda. Willkie’s First-Amendment arguments ended any further investigation. Around this same time, he was asked to join the Board of Directors of Twentieth Century-Fox and soon became Fox’s Chairman.

Willkie’s views on race were equally advanced. He had previously advocated integration of the military and civil service. Willkie now urged appointment of an African American to the cabinet or the Supreme Court. He continued to be a strong advocate for equal rights for minorities. In 1943, Willkie worked with the then Chairman of the NAACP, Walter White, to convince Hollywood to give black Americans better treatment in the movie industry.

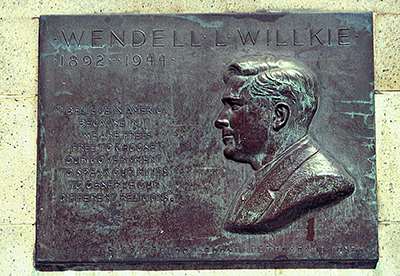

Memorial plaque to Wendell Willkie on the grounds of the New York Public Library. The inscription reads:

“I believe in America because in it we are free-

free to choose our government, to speak our minds,

to observe our different religions.”

The final chapter of the Roosevelt-Willkie partnership is perhaps even more fascinating than the collaboration described here. Although some political historians are aware of certain of the facts, most have only vague knowledge of the fact that Roosevelt asked Willkie to be his Vice-Presidential running mate in 1944, the president’s successful attempt to earn an unprecedented fourth term. When Willkie declined the invitation, Roosevelt dispatched his Special Counsel, Samuel L. Rosenman, to New York to have highly confidential discussions with Willkie about Roosevelt’s “long term project…after the 1944 election to start to form a new party with Willkie” – a more moderate hybrid or fusion party – that would free American politics from isolationism by jettisoning the extreme right or left of both parties.

Sadly, it never came to pass. Willkie died in October of 1944. Roosevelt passed away less than six months later, in April of 1945.

While it’s unlikely that the current crop of bickering candidates will soon provide anything like the legendary non-partisan cooperation evinced by these two men, perhaps the rancor and dysfunction of the 2016 presidential campaign will finally provoke the American public to seriously consider the formation of a new party — one freed from extremism — that was so presciently contemplated by two of America’s most astute politicians over 75 years ago.

Retired attorney, avid history buff and Foundation Alumni Advisory Board member C. Stephen Heard Jr. ’58 wrote his senior honors thesis on Wendell Willkie. He lives with his wife Susan in Charleston, South Carolina.

A printer friendly version of this article can be downloaded HERE.