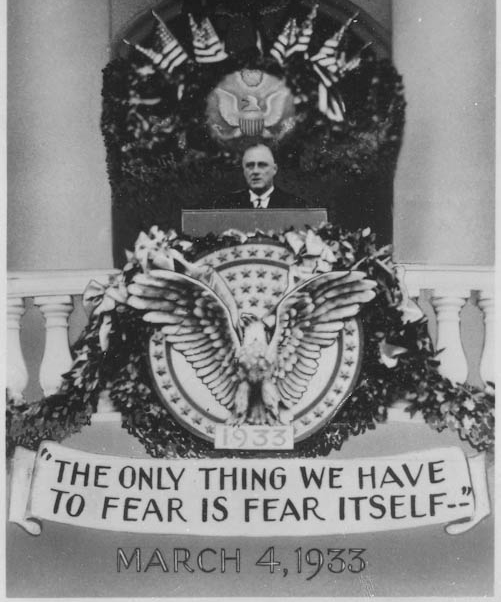

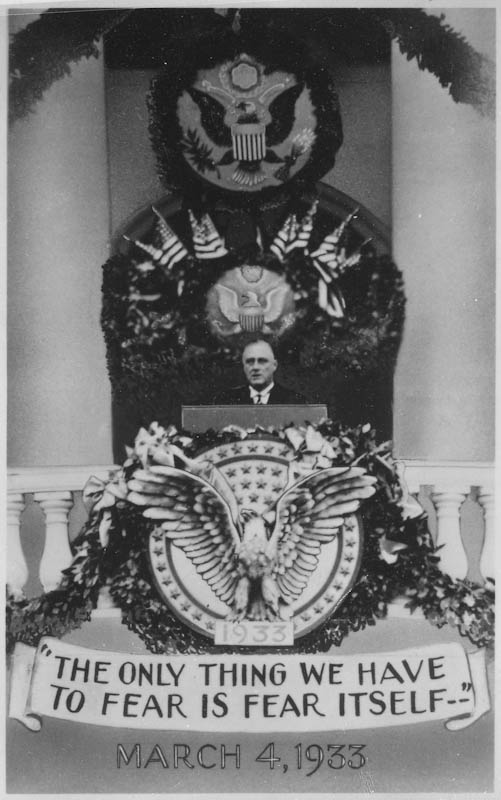

Franklin D. Roosevelt delivering his inaugural address, March 4, 1933. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, image 48224291.

The chronically insecure Richard Nixon appointed a Hundred Days Group to try to ensure passage of the requisite amount of legislation in his first hundred days.

Newt Gingrich declared one in 1995, pledging that the Contract with America would be passed in one hundred days.

In 2011 Andrew Cuomo congratulated himself on a successful first hundred days when the New York legislature passed an on-time budget for the first time in many years.

And so it has been for elected officials since 1933—many of them trying to evoke for themselves the warm glow of accomplishment that accrued to Franklin Roosevelt after his famous first hundred days, March 9 to June 16, 1933.

Much is being made today about the impending end of President Trump’s first hundred days and whether his record of accomplishment will live up to his promises. But it was the news media, not Franklin Roosevelt, who gave the benchmark its name. Its origins might give students of history pause.

The first “first hundred days” marked the period between Napoleon’s return from exile on the island of Elba on March 20, 1815, the turbulent battles including his defeat at Waterloo that ensued, and the second restoration of King Louis XVIII—under escort from the Duke of Wellington—on July 8, 1815. (It was actually a period of 111 days, but the French are not such sticklers for precision in the face of a grand pronouncement.) Thus it was the prefect of Paris, Gaspard, Comte de Chabrol, who first used the term “les Cent Jours” in welcoming the return of the king and the Bourbon monarchy. Were the newsmen of 1933 being ironic in dubbing the Roosevelt’s first months in office a modern-day “cent jours”?

We will never know, but it may be worth revisiting the historical context of the modern concept of the hundred days. Roosevelt took office at a time of unparalleled national despair. Trump may have described the country as beset by American “carnage” in his inaugural, but it is impossible for us to imagine the state of the nation when Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933.

A string of bank closings beginning on February 14 had sent the nation’s financial system into a new crisis. Most of the nation’s banks were closed. On inauguration morning the governors of Illinois and New York closed the Chicago and New York stock exchanges.

These were the final weeks of what historians have come to call the “interregnum,” the seemingly interminable four months between the election and inauguration of FDR. After this terrifying episode of presidential limbo, Inauguration Day was changed from March 4 to January 20.

But the conditions in 1933 were just the most recent in a series of economic disasters. Since 1929 the Great Depression—the deepest and longest in our history—had tested the endurance of Americans. Eighty years later the grim statistics of life in the United States in 1933 remain shocking.

Depression era breadline, New York City, 1932. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, image 7420(244).

In a population of about 125 million, one in four workers was jobless. In industrial cities like Youngstown, Ohio, close to three-quarters were unemployed.

Nineteen million Americans depended upon meager relief payments to survive. There was no national safety net.

Those lucky enough to have jobs earned (on average) 30 percent less than three years earlier.

Over 1,300 municipalities—and many states—had defaulted on their obligations to creditors.

Two statistics, selected from thousands, capture the sense of paralysis that gripped the nation.

- In 1929 the US Steel Corporation—a cornerstone of the American economy—boasted 225,000 full-time employees. In 1933 it did not have a single full-time worker.

- The nation’s farmers were in even worse shape. Farm prices fell 53 percent from 1929 to 1932; farm income fell 70 percent. By early 1933, 45 percent of farmers were delinquent on their mortgages.

Violence erupted at farm foreclosure sales and the homeless gathered in tent cities called Hoovervilles.

Some voices, fired by desperation and fear, even called for a suspension of constitutional government and near-dictatorial powers for the president. Instead the new president famously declared in his first Inaugural Address:

This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.

He called for “action, and action now.”

Immediately on taking office, the banking crisis consumed the president and his advisors. Columbia law professor Raymond Moley, head of Roosevelt’s Brain Trust, and the new Treasury Secretary William Woodin worked day and night with Hoover’s financial team, including former Secretary of the Treasury Ogden Mills and other holdovers from the previous administration.

The plan they adopted was essentially that of Hoover’s team, a conservative approach designed to save rather than subvert the capitalist system.

On his first full day in office, by executive order, Roosevelt declared a four-day national banking holiday effective Monday, March 6.

He then called Congress to Washington in special session. Their first task was to pass legislation under which the banks could be reorganized and reopened.

On March 8, to explain the banking plan, FDR held the first of the 997 press conferences of his twelve-year presidency.

On March 9, five days after his inauguration, he signed the Emergency Banking Relief Act. It gave him broad discretionary powers over banking and currency and was introduced, passed, and signed in less than eight hours.

Roosevelt’s advisors believed it was key to get people to deposit, not withdraw, their savings from the banks. To explain the plan to the public, the president delivered his first Fireside Chat, on banking, on March 12.

In plain language Roosevelt spoke to the America people as if speaking to a single family gathered around their firesides.

He calmly and clearly explained the reorganization. “My friends,” he said, “ I want to talk for a few minutes . . . about banking. . . . I want to tell you what has been done in the last few days, and why it was done, and what the next steps are going to be.” He explained the phased reopening of the banks, concluding by asking the public to return their savings to the reorganized banks. “My friends,” he assured them, “it is safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than it is to keep it under the mattress.” Amazingly, people returned their precious savings to the re-opened banks.

The people also began a national conversation with their new president. In the week following his inauguration, more than 460,000 people wrote to FDR. He was forced to replace Hoover’s one mailroom clerk with a staff of fifty; over the course of his presidency, an average of six thousand people a day wrote to their president.

On March 16 Roosevelt decided to keep Congress in session to move forward on the relief and reform measures that would address systemic problems in the financial system, agriculture, and industry—and meet the immediate problems of food, shelter, and work for the suffering masses.

The list that follows is the standard of accomplishment that has proved an elusive benchmark for every president who followed.

March 20, Economy Act. Ironically, an attempt to reduce the budget—this act cut veterans’ pensions, reduced federal salaries by 15 percent, and reorganized several government agencies. It was the opening salvo of the New Deal. Like most Democrats, FDR believed a balanced budget would put the government on sound financial footing. So the regular federal budget actually contracted even as the new emergency spending skyrocketed. He believed the Economy Act would save $500 million; the actual saving was about $240 million. The real value was probably in terms of morale, a signal of the new administration’s determination to act decisively.

March 22, Beer–Wine Revenue Act. As the repeal of the Volstead Act of 1919 made its way through the states, the Beer–Wine Revenue Act legalized the sale of wine and beer that contained no more than 3.2 percent alcohol—and people rejoiced. The act went into effect on April 7. The 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment, was enacted on December 5, ending the failed experiment of Prohibition.

March 31, Civilian Conservation Corps Reconstruction Relief Act. This act created 250,000 road construction, soil erosion, flood control, national park, and reforestation jobs for young men on relief between the ages of 18 and 25. Those employed received $30.00 weekly, $25.00 of which was sent to their families. The CCC employed more than two million young men (referred to as “Roosevelt’s Tree Army”) by the end of 1941 and is credited by some historians with a vital role in preparing young men for the war effort.

April 19, Abandonment of Gold Standard (executive order). This brought about a decline in the dollar value abroad, but commodity, stock, and silver prices increased on American exchanges.

May 12, Federal Emergency Relief Act. This act vastly enlarged and reorganized Hoover’s Emergency Relief Act. It was administrated by Harry L. Hopkins and was replaced by the WPA in 1935. Half of the $500 million appropriation was allotted to the states.

May 13, Agricultural Adjustment Act. At the time about 30 percent of the American workforce was agricultural. The AAA was designed to raise farm prices by cash subsidies or rental payments to farmers in exchange for curtailment of production and by establishing parity prices for certain basic commodities. Funds came from taxes levied on farm product processors. This feature of the AAA was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1936.

May 18, Tennessee Valley Authority Act. This act authorized the TVA to construct dams and power plants and to produce and sell electric power and nitrogen fertilizers in a seven-state region. It inaugurated Roosevelt’s vision for progressive land and social reform, model communities, and resettlement, reforestation, and agricultural educational programs. It also provided the basis for the Sunbelt, the industrial development of the Tennessee Valley. Between 1933 and 1945, electrification grew from about 2 percent to 75 percent of the population in the Tennessee Valley.

May 27, Federal Securities Act. This act required most new securities issued to be registered with the Federal Trade Commission and established the Securities and Exchange Commission.

June 5, Abandonment of Gold Standard. FDR signed the gold repeal joint resolution—which canceled the gold clause in all federal and private obligations—making all debts and contractual agreements payable in legal tender.

June 13, Home Owners Refinancing Act. This act authorized the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) to refinance nonfarm mortgage debts. HOLC made loans on about one million mortgages by June 1936, or about 20 percent of the nation’s mortgages.

June 16, National Industrial Recovery Act. This act created the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and established regulatory codes for control of numerous industries. Employers were exempted from antitrust action; employees were guaranteed collective bargaining and minimum wages and maximum hours. The second section of the act established the Public Works Administration (PWA), which provided employment by public works construction. The PWA spent more than $4 billion on 34,000 public works projects. In 1935 the Supreme Court declared the NIRA unconstitutional.

June 16, Glass–Steagall Act. The Glass–Steagall Act created the Federal Bank Deposit Insurance Corporation, which guaranteed bank deposits, separated investment from commercial banking to halt speculation with deposits, and widened the powers of the Federal Reserve Board. The Graham–Leach Act of 1999 repealed important provisions of this act, leading—many observers say—to the abuses that resulted in the recession that started in 2008.

June 16, Farm Credit Act. This act reorganized agricultural credit activities and agencies.

June 16, Emergency Railroad Transportation Act. This act created the office of federal coordinator of transportation and gave the Interstate Commerce Commission supervision over railroad holding companies. It tried to smooth out operating duplications and inefficiencies and required national railroads to limit layoffs due to consolidation.

***

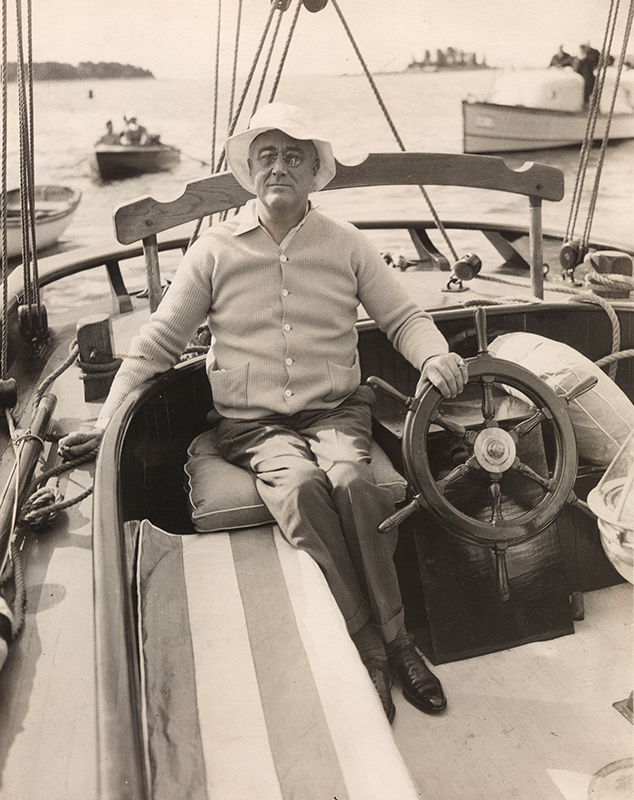

And then — and only then — Franklin Roosevelt took a vacation. He left Washington for a sailing vacation and returned to the family vacation home on Campobello Island, for the first time since contracting polio there in 1921.