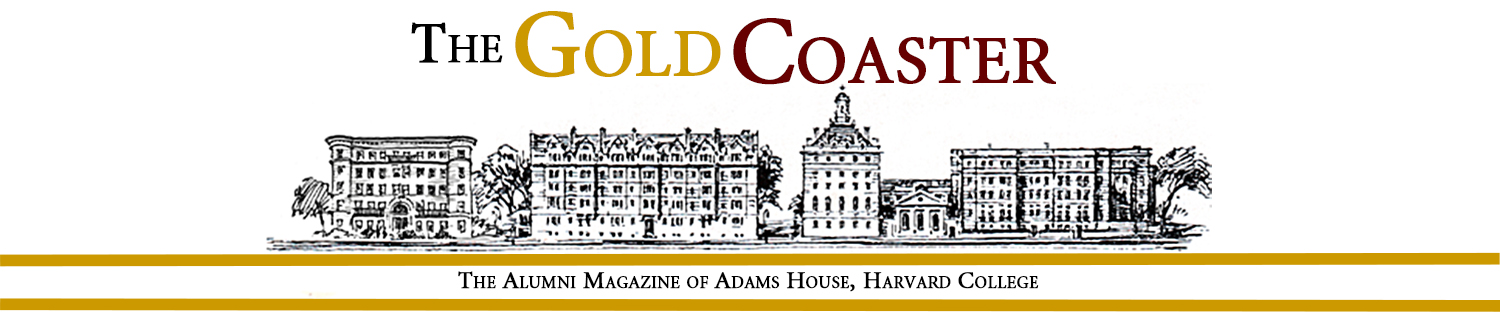

The original floor plan for Randolph Hall. The Coolidge Suite is the wing to the left, with the breakfast room in the left hand corner.

Chances are if you lived in Adams any time before the early 2000s, the label Coolidge Room would have meant little or nothing to you. And even if it did, most likely your memory would have involved some interesting but darkened murals and a large ornate fireplace, some dusty books and large table for studying. In short just another quirky space in Adams that had obviously been something, but no one was really sure what or why.

In fact, the Coolidge Room has the sole distinction at Adams of being born in mystery, forgotten; rediscovered partially, forgotten; rediscovered, partially forgotten again; and finally restored to its former original glory, its history now (reasonably) preserved for posterity.

Are you with me so far?

Let’s begin at the beginning. Randolph Hall was built in 1897 by then-professor Archibald Cary Coolidge (A.C.C. hereafter). He had purchased Apthorp House and its adjacent gardens with the idea of creating a residence hall at Harvard along English lines, which would include a fairly palatial suite of rooms for himself. According to an 1897 Crimson article: “The building alone cost $160,000 and is planned with all possible conveniences. There are fifty suites ranging in prices from single rooms at $200 to double rooms at $700. In each room there will be telephones connecting with the janitor’s room, and besides the exercise and reading rooms on the ground floor there is to be a breakfast room open only to those rooming in the building.”

It is to this “breakfast room” that we now turn. First of all, you may wonder, why a breakfast room and not a dining room? The answer lies in the social status of the young men who were to occupy these luxury rooms. Most, if not all, came from very wealthy families, and took their meals, for the large part, in private clubs. Therefore, the sole meal of the day that might have had some appeal to eat in-house was breakfast, where you could dine in total comfort before sortieing out into the hurly-burly of 19th century Cambridge. The Randolph breakfast room was particularly fine, with a large, crackling fire in an ornate hearth, rich paneling, and a full bank of window seats looking southward over Mt. Auburn Street. It must have been the perfect place to contemplate the start of the new day, especially after having arrived back just a few hours before from a champagne-soaked ball at the Somerset or the Brookline Country Club.

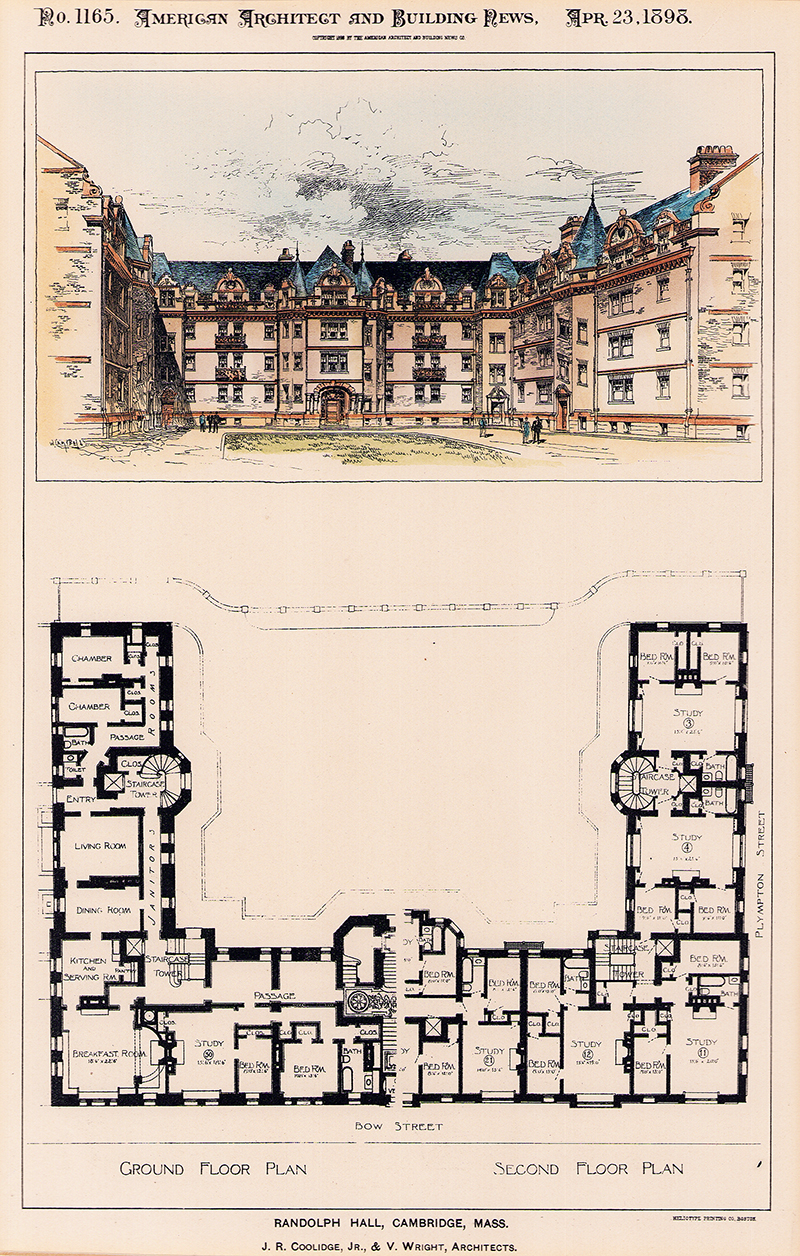

Penfield’s 1894 cover for Harper’s

Sometime about 1902 or 03, A.C.C. commissioned Edward Penfield, the distinguished American poster artist, to decorate the room with a series of panels showing scenes from Harvard life. As a 1903 article in Good Housekeeping noted “Usually the commissions for such works are placed with artists whose names are made in that particular field of art and whose business is apt to be within the academic principles of decoration handed down from the early Italian masters. These look upon all purely modern art as ephemeral when not positively degenerate. It was therefore a departure from custom to give this commission to an artist whose fame was made in the poster field. As a designer of magazine posters, indeed, Mr. Penfield enjoys an international reputation. But this did not qualify him in the eyes of everyone for the more serious undertaking of decorating a branch of an important institution…”

This was, in truth, a considerable understatement, as the selection of Penfield, who had become famous as the cover artist for Harper’s Magazine, would have seemed closer to revolutionary. Penfield defined avant-garde, having essentially created the look of the American poster, with his simplified, elongated figures, bold colors, solid monotone backgrounds and curved, art-nouveau lines. In fact he is considered the father of American poster art, and on the same level as Toulouse-Lautrec, whose work Penfield’s somewhat resembles. In 1903, Penfield had recently married and left Harpers to set up his own independent studio, so the timing was perfect to take on this private commission. The specifics of the contract, its duration, and cost however have all been lost to history.

Yet there was no denying the murals’ success. The Good Housekeeping article continued. “The result however, speaks for itself. Mr. Penfield has very obviously had the finer principles of his art well in hand, and what is much more rare, he has put on canvas something of the real spirit of his time, at least as that is exemplified in the life at Harvard.”

These murals remained tucked away from view to all but a select few until 1916, when Coolidge sold the building to Harvard. At that point the breakfast service was probably suspended, and the room closed, as the next mention comes from an article in the Christian Science Monitor in 1937, which notes that assistant professor of Government (and former student of A.C.C.) reopened the room, “closed until this year,” as his office. (As a fascinating aside, Bruce Campbell Hopper, WWI aviator, historian and diplomat deserves an article all of his own. But that is a story for another day…)

Penfield self-portrait with monogram

No one at the time remembered who had painted the murals, however, until Stuart D. Preston ’06 wrote to the Crimson informing them that “those murals in the breakfast room of Randolph are the work of Edward Penfield, one of the best known artists of his day.” “No rooms in college,” he continued, “were complete without a few Gibson Girls (painted on the walls, of course), and some of the works of Penfield. Every month, indeed, Scribner’s Magazine issued a large poster done by the aforesaid Mr. Penfield.”

So that explained the selection of Penfield: Coolidge very cleverly chose one of the most popular artists of the day among Harvard students to decorate his breakfast room, which must have been quite a coup at the time. (Remember, too, that Randolph was private for-profit lodging, and competed with the other buildings along Mt. Auburn for potential tenants.)

Reopened as an office in 1934, it would be here that in 1939 and 40, a young J.F.K. would meet to discuss his thesis with Professor Hopper, a work which barely earned an honors credit at Harvard but ultimately became the book, “Why England Slept”—thanks to some major interference run by papa Joseph Kennedy, who was never afraid to jump into the melee for his boys. Kennedy’s thesis, largely an apologia for his father’s pro-Nazi sympathies while Ambassador to the Court of St. James, also reflected his own support for the first America First movement, which sought to keep the U.S. out of foreign entanglements. Pearl Harbor brought an abrupt end to such fanciful speculations.

Fast forward another quarter century to 1964. Coolidge had died in 1928, but not before becoming the first University Librarian and founding the highly influential publication Foreign Affairs, along with the eponymous Council. Some of his former students, including Bruce Hopper, who had retired from Harvard in 1961, lobbied for the creation of a memorial to Coolidge. Through their efforts were born the Archibald Cary Coolidge Room and its collections.

Remarkably once again, no one in 1964 could remember who painted the murals, which were by this time almost entirely covered by soot, smoke and grime. A minor cleaning was done, but despite research by the director of the Fogg, it is unclear whether or not the authorship was rediscovered or appreciated. (We should note here that Penfield often didn’t sign his work, but rather used a monogram.) At the time, Penfield’s work, along with the other artists of his day, was then at its lowest popular ebb, and must have seemed remarkably old-fashioned in the psychedelic sixties. Coolidge was the focus of the room and memorial. The murals were merely incidental.

By the early 2000s, Coolidge was barely remembered, and the room had become shoddy. Restored under the Palfreys, the murals were professionally cleaned and for the first time given proper lighting. And while their attribution had been recovered, the subject matter of some of the panels was no longer recognized, and it was not until the Foundation took up the research banner in the early 10’s that John the Orangeman, the old boat house, and several other subjects were properly identified.

Finally, the just-completed renewal of Randolph Hall involved the removal, cleaning and reapplication of the panels, as well as climate control and museum-quality lighting for the space.

Today we recognize the room for what it is: a museum-class work of art by one of the greatest American illustrators of all time, in a setting memorializing one of the most remarkable intellectuals of early 20th century Harvard. (Oh, and the Kennedys were there too.)

Hopefully this time we won’t forget.

Walking to ‘The Game” This would have been the first year of Harvard Stadium, 1903

John the Orangeman and the old Harvard boat house of Teddy Roosevelt’s time

The main hearth. To the left, Commencement activities and to the right, a portion of the Hasty Pudding Panel

The baseball caught in a second of time. Hit or miss? We’ll never know.

From left to right, the old boat house, polo, crew, basketball, golf, track and baseball