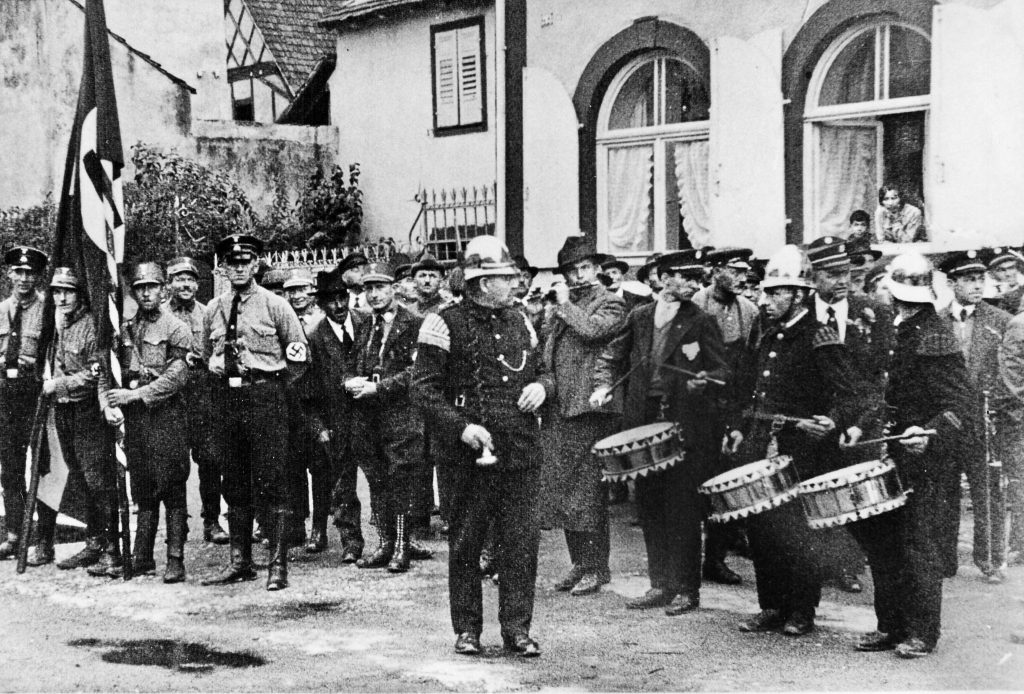

Nazi Brownshirts gather with the Kippenheim fireman’s band, 1935.CreditCreditHans Wertheimer

By Anna Altman

[BOOK REVIEW]

THE UNWANTED

America, Auschwitz, and a Village Caught in Between

By Michael Dobbs

On the morning of Nov. 10, 1938, Hedy Wachenheimer rode her bike from her small village of Kippenheim to school in the next village. A Jewish girl of 14, Wachenheimer was accustomed to being ostracized. But that day felt different. On her way to school, she saw that the windows of Jewish businesses had been smashed. As she waited for lessons to begin, the usually gentle principal pointed at her and yelled, “Get out, you dirty Jew!”

Kristallnacht was a turning point for the tightknit community of Jewish families who had lived in Kippenheim for five generations. Over the next four years, its 144 Jewish residents suffered dispossession, and the indignities and crimes of their Nazi overlords.

In “The Unwanted,” Michael Dobbs, a former reporter at The Washington Post, tells the story of the town’s Jews as they desperately sought a path to a new life elsewhere. Most hoped to find refuge in the United States. Dobbs weaves the tales of their declining fortunes with a carefully researched account of American attitudes and policies toward Europe’s Jewish refugees. American diplomats in Europe tried to grant as many visas as possible while State Department officials threw up roadblocks. As Eleanor Roosevelt tried to…

Read more at:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/24/books/review/michael-dobbs-unwanted.html

(*can purchase book with affiliate code through the link)