Choosing (and Being Chosen By) Adams

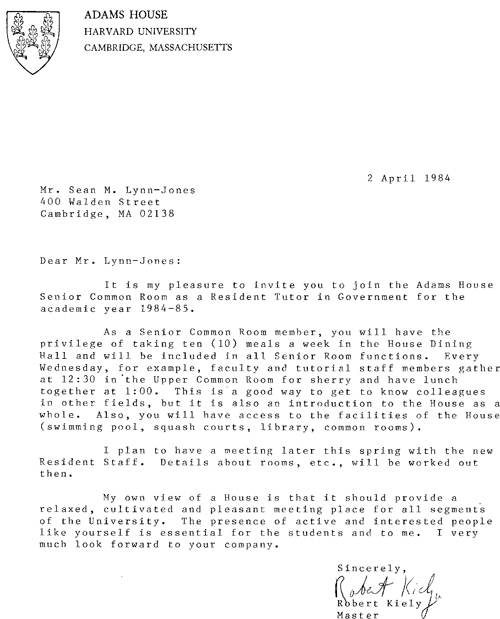

In the spring of 1984, I was a graduate student in the Department of Government at Harvard. For several years, I had aspired to become a resident tutor in one of Harvard’s houses. I hoped that living in a house would provide a sense of community, which was sorely lacking in the lives of most graduate students, not to mention free food and housing. Although I had been a nonresident tutor at Dudley House and then Currier House, I applied to be a resident tutor in Adams, mainly because Jeff Rosen ‘86 told me that Adams might be looking for a Government tutor and encouraged me to apply.

At that time, Adams House had a very pronounced image as the “artsy-fartsy gay house.” The stereotype oversimplified the character of the house, but there was no doubt that Adams House was more bohemian, fashionable, tolerant, diverse, and creative than any of Harvard’s other houses, even if it lacked a large population of varsity athletes. My friends joked that I didn’t seem to fit the Adams bill at all: I was straight, my artistic, dramatic, and musical talents were extremely well hidden, and the only black items in my wardrobe were socks. Nevertheless, I convinced myself that tutors didn’t have to fit the stereotype of their houses and enthusiastically applied to Adams, met with Master Robert Kiely and several students, and was pleasantly surprised to receive very soon after an offer of a resident tutorship.

I did not respond immediately, however. I had also applied to be a resident tutor in Leverett House. Adams had some clear advantages: the food was reportedly better, I had heard that the rooms were nicer, and the house was conveniently located near the Yard and the heart of Harvard Square. Adams, of course, also had the unique advantage of having its own opulent and notorious swimming pool. (For the most complete and revealing history of the Adams House pool ever published, see HERE. One of the most important perks of being a resident tutor was having a key to the pool.) Leverett had in fact offered me a tutorship first, however, and its masters seemed very eager to have a resident Government tutor, so I remained undecided while I considered both offers.

In the end, I made my decision after thinking about what St. Patrick’s Day tea had been like at Adams House. Master Kiely had invited me to that tea so that I could get to know Adams House while I was applying. In the elegant confines of Apthorp House, Irish coffee, Jameson Irish Whiskey, and Guinness had all flowed freely. Irish step dancers and musicians provided entertainment. To top it off, Seamus Heaney, the greatest living poet in the English language (and sometime Adams House resident) read his poetry. Leverett House simply couldn’t compete. I chose Adams.

G-Entry and Doug Fitch: 1984–85

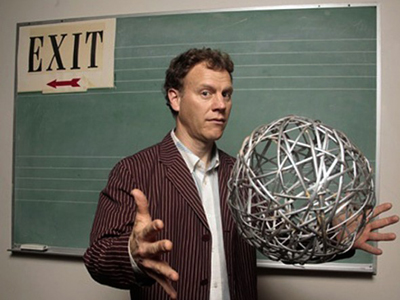

In the fall of 1984, I moved into G-33. It was a relatively small room, but its bedroom and living room featured darkened oak trim, a fireplace, hardwood floors, and a view of the Lampoon. (I could watch their goings-on through the window; their parties could keep me up all night.) G-entry was not a very large entry, but for some reason it had two resident tutors. Doug Fitch ‘81, the other tutor in G-entry, had lived in Adams as an undergraduate and introduced me to many of the best traditions of the house.

The incredible Doug Fitch Doug first enlisted me to pose as if I were part of various pieces of furniture while he took photographs. He explained that he had a client who wanted furniture that looked like human bodies. Doug’s photographs would be the basis of visualizing what assorted pieces of this furniture would look like. Along with several other people, I lay on the floor in the squash courts and held my arms and legs up as if I were supporting a tabletop and otherwise contorted myself into different positions. It was very much like a game of Twister. I don’t know if Doug ever created any furniture for his client, but his website (www.dougfitch.com) includes plenty of images of similarly outlandish furnishings and interior designs.

Doug also introduced me to the Bow & Arrow Press in the basement of B-entry. We spent most of one night making a linocut of a brain and using it to print posters to promote a concert by a student rock band called the “The Whacked” (or was it “The Wacked”?). I never printed anything else in the Press, but I was proud to see one of those posters hanging on the walls many years later.

On November 5, 1984, Doug knocked on my door in the middle of the afternoon, chanting, “What a day, what a day, for an auto-da-fé.” I was mildly alarmed by this prospect, but before I could inform Doug that I had other plans, he explained that we were going to burn Ronald Reagan in effigy to celebrate Guy Fawkes Day—a British holiday that features fireworks and the burning of Guy Fawkes in effigy on November 5 to commemorate the failure of Fawkes to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605. It was an offer I couldn’t refuse. Doug and several co-conspirators had already stuffed a dummy and put a Reagan mask on it. As we generated something akin to music on our kazoos, we marched the effigy to the banks of the Charles, ignited it, and threw it into the water without being apprehended by Harvard’s Republicans, the Cambridge Police, the Fire Department, or the Environmental Protection Agency.

What I Did as a Resident Tutor

I had multiple functions as a resident tutor. Like all resident tutors, I had some responsibilities for the entry where I lived. In addition to hosting entry parties and study breaks, I was supposed to ask students to keep their parties quiet. In my eight years in Adams House, however, I rarely had to do so. As time went on, Harvard and Adams House devised new rules and paperwork for monitoring parties, but my first few years in the house were blissfully free from such burdens.

As the Government tutor, I taught the department’s sophomore tutorial to Government concentrators, signed study cards, offered general advice, and unofficially advised seniors who felt neglected by their official (faculty) thesis advisors. Despite its reputation as a haven for literati and Visual and Environmental Studies concentrators, Adams had a surprisingly large number of Government concentrators.

I also attempted to run a Politics and Society table with Jeff Herf, a resident Social Studies tutor. Unfortunately, this project was never entirely successful. Jeff and I would invite senior faculty and visitors to Harvard to dinner, only to find that no more than a handful of students had time to join us. Most undergraduates were too busy to set aside an hour or more for these dinners.

My main house-wide duty was to be the housing tutor. Although most houses assigned responsibility for housing to the assistant to the masters, the task was much more complex in Adams and had been delegated to an assistant senior tutor. Many Adamsians tended to have strong and idiosyncratic personalities, which meant that there were lots of roommate conflicts and requests to switch rooms. Adamsians also were likely to study abroad or to take time off, so every January there were many vacant spaces to fill and returning students to assign.

I spent many evenings listening to students tell tales of woe about the outrageous behavior of their roommates and the ample reasons why one or all of them absolutely required a single room—or at least a new roommate. Even if there was a lot of self-serving exaggeration, I was exposed to what would later be called “Way Too Much Information” about the personal habits that made roommates incompatible. All those students can rest assured that I kept no records and time has erased my memories of most of the embarrassing details of those conversations. After hearing all the complaints, I usually found a way to reshuffle roommates in a series of chain-reaction moves that relocated those who wanted to move through a combination of roommate swaps and placing the discontented in vacancies created by students who departed at the end of the first semester. Students who remained dissatisfied glared at me in the hallways and dining hall.

I also ran the annual housing lottery, which was always a spectacle, with a game-show atmosphere and screams of ecstasy (I remember an emphatic “Praise Vishnu!” from a happy student) and groans of despair. The lottery was far more stressful for the students who were picking rooms than it was for me, but I had to spend a lot of time running the lottery and devising rules that would allocate rooms fairly. (As housing tutor, I never forgot the advice my predecessor, Aaron Alter ‘79 gave me: “Whatever you do should be fair, but it’s even more important that it appear to be fair.”) Every year there were a few changes in the rules and room configurations. In the early 1990s, for example, I created what were probably the first “official” coed suites at Harvard. By opening a fire door, two adjacent suites could become one large suite that could be chosen by a coed group. University Hall administrators were none the wiser, because the suite appeared as two single-sex suites on their room lists.

One of the most difficult and frustrating aspects of being housing tutor was having to deal with dozens of requests to transfer into Adams House. Many students felt miserable in other houses and fervently believed that their only road to happiness lay through Adams House. In many cases, they probably were right, although some almost certainly were just hoping to escape the Quad. I met with many transfer applicants and tried to find space for the ones who truly seemed to belong in Adams House, but there was never enough room for all of them.

From time to time, I also served on the Adams House fellowship committee, which interviewed candidates for various major scholarships such as the Rhodes and Marshall and helped Adamsians with their applications. I envied the fellowships tutors, because they generally saw Adams House students at their best, whereas I usually saw them at their worst—when they were whining about their roommates.

I briefly was acting senior tutor (now the resident dean) when Senior Tutor Janet Viggiani was recovering from surgery. During those weeks I sat on Harvard’s Administrative Board as it deliberated the fate of several students—including at least one Adamsian—who had run afoul of Harvard’s rules.

The Dining Hall

In the 1980s, the Adams dining hall was a distinctive and somewhat daunting place. Adamsians of that era will recall the complicated geography of the dining hall and the maps that students drew to designate which groups ate at the various tables. When I moved into Adams, the dining hall was divided by the salad bar into smoking and nonsmoking sections. Black-clad smokers puffed their Gauloises on the half of the dining hall closest to the windows on Arrow Street, while diners closer to the checker’s desk and the entrance from the Gold Room hoped the smoke would not waft their way. Within a few years, the smokers were confined to the tables along those windows. Next, smoking was banned altogether, although the students most likely to smoke still frequented the window tables.

The dining hall was also a scene for various forms of flamboyant display—and not only on the annual Drag Night. A student from another house told me she ate in Adams when she needed new ideas for her wardrobe. Several Adamsians were invariably on the cutting edge of fashion and observers keenly anticipated what they would wear.

As a tutor, I ate most of my meals in the dining hall, where the food was usually delicious and always free. I tried to navigate the intimidating geography of the dining hall and to eat with various groups at their favorite tables, even if some didn’t seem to welcome being joined by a tutor and there were times when interhouse diners packed the dining hall and made it hard to find any Adamsians. Although once in a while I would sit down with a group of students who promptly left, I usually found a place at a table. (This process surely would have been much more intimidating—for me, at least—if I had been an undergraduate.) One of the most enjoyable aspects of being a tutor was the opportunity to have long conversations with students over dinner.

The Vanderbilt Suite: B-22

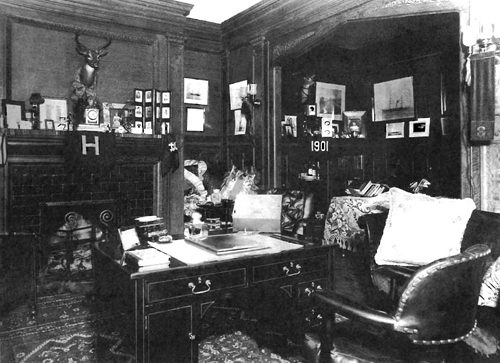

I had the incredibly good fortune to move from G-33 to B-22 after my first year in Adams House. G-33 was a good room, but B-22 was an extraordinary suite. When Westmorly South (now B-entry) had been built as a private Gold Coast dormitory in 1898, B-22 had been decorated to suit the tastes of its first resident, William Kissam Vanderbilt, Jr. The suite featured darkened oak wainscoting and pilasters, built-in bookcases, carved linenfold doors, and an imitation-beamed ceiling. It had retained antique light fixtures and a chandelier. Its most dramatic element was an arch that led from the living room into the study. Cherubs and vines were carved into the wood on either side of the arch. Like many B-entry suites, B-22 also had diamond pane windows and French doors, a large fireplace, and hardwood floors.

Other tutors coveted B-22 when it became vacant with the departure of Aaron Alter. I was never sure why Bob Kiely assigned it to me, but it seemed appropriate that if I was willing to take over Aaron’s responsibilities as housing tutor I also should succeed him in B-22.

After moving into B-22, I tried to furnish and decorate the room in the manner that it deserved. A mahogany dining room set and sideboard that I had inherited from my grandmother perfectly complemented the woodwork. A trip to Paine Furniture (where Franklin Roosevelt had shopped for items for his B-entry room) yielded a Chinese Chippendale sofa and a mahogany coffee table. A few antiques, potted plants, and an assortment of framed prints completed my efforts to decorate the room. I never achieved the level of clutter and colorful ornamentation associated with Harvard rooms of the Gold Coast era (see the FDR Suite for an outstanding attempt to replicate the style of undergraduate rooms circa 1900 ), but I felt that I had done justice to the suite.

I also started to think about B-22’s potential as a venue for parties. The privilege of living in the room came with the responsibility of using it for the greater good.

Planning the Perfect Entry Party

One of the duties of resident tutors was to hold a party for the students in each entry at the start of each semester. Shortly after moving into G-entry, I asked Doug Fitch if we should schedule a party and order some pizza and beer. Doug was appalled by my choice of food and drink and insisted that only champagne and caviar would do for an entry party in Adams House. Thus began my quest to hold the most lavish and memorable entry parties possible. Doug and I hosted G-entry parties that invariably featured cheap champagne and low-quality caviar, but these were still an improvement over pizza and beer. Doug had a leather pig that always served as the centerpiece at these parties. We impaled cornichons on toothpicks, inserted them along the pig’s spine, and dubbed it the “cornichon pig.”

After moving to B-entry, my fellow entry tutors Gino Lee ‘84 and (subsequently) George Ho ’90 enthusiastically joined my efforts to take entry parties to new heights. We planned parties that thematically integrated music, food, video entertainment, and decorations. As the Bow & Arrow Press tutor, Gino designed and printed invitations.

Gino and I hosted a series of three “pop icon” themed parties. The first honored Andy Warhol, whom Gino admired, and took place in the Bow & Arrow Press. We covered the walls with silver Mylar to simulate the look of Warhol’s “Factory” in New York and hung a few Warhol posters. The stereo played the Velvet Underground and Nico album that featured Warhol’s painting of a banana on the cover and “Songs for Drella,” which Lou Reed and John Cale recorded as a tribute to Warhol. Cans of Campbell’s soup were stacked around the room. On the television, the VCR played movies such as “Andy Warhol’s Dracula” and “Ciao, Manhattan,” the semi-biography of Edie Sedgwick, a Warhol acolyte who was a habitué of Adams House in the 1960s. We copied and posted the Adams facebook photographs of all the residents of B-entry and provided brushes and paint in various Warholesque shades so that each student could color their photograph to resemble Warhol’s famous portrait of Marilyn Monroe. It was hard to think of thematic food to serve at the party (speed and other illicit substances were suggested), but few complained about champagne and caviar.

The second pop icon party took David Lynch and his works as its theme. We hosted it as the nation was becoming obsessed with Lynch’s 1990–91 “Twin Peaks” television program. Students were asked to dress as a character from “Twin Peaks” or one of Lynch’s movies. At least one “log lady,” a one-armed man, and a murder victim or two wrapped in plastic sheets attended.

Selecting food for the David Lynch party was simple. Taking our cue from “Twin Peaks” we served plenty of coffee (“cup of Joe”) and doughnuts.

The theme music from “Twin Peaks” eerily blared from the stereo and wafted through the Bow & Arrow Press. The television, however, featured Lynch’s horrifying and grotesque “Eraserhead,” with its bizarre characters and disturbing images of a mutant baby. A jaded Adamsian looked at the screen with disdain and declared, “I hate ‘Eraserhead.’”

It was hard to ignore Madonna in the late 1980s and early 1990s, so she was the focus of our third pop icon party. There was no shortage of music and the choice of food seemed obvious: aphrodisiacs. Along with the customary champagne, we served vitamin E, chocolate, and ginseng.

We hosted many other B-entry parties that were not part of the pop icon series. Every year I held a Christmas party in B-22. I lugged home a tree from the now long-defunct Grower’s Market on Memorial Drive and erected it on my dining room table. My large desk served as a buffet that featured cakes, a Linzer Torte, and fresh strawberries for dipping in chocolate fondue. One year Gino and I held a Halloween party in the Bow & Arrow Press. Using a lot of cans of Sterno and several frying pans, I cooked Crêpes Suzette for about four dozen people. Some dry ice in the bottom of the punchbowl created a bubbling cauldron. We had so much dry ice that we used it to fill the Press with fog. The door was open, so tongues of fog eerily crept into the tunnels and spread out under Adams House. Another party took place in the Adams pool, which was drained for repairs. Searching for a new theme, we seized on the Fine Young Cannibals’ album, “The Raw and the Cooked,” and shucked raw oysters and clams in my suite. (The knife often slipped and I can still see the gouges in my coffee table.) A pre-Valentine’s Day “love or pas de love” soirée invited partygoers with mixed emotions to wear red or black as they experienced George Ho’s appropriately themed art.

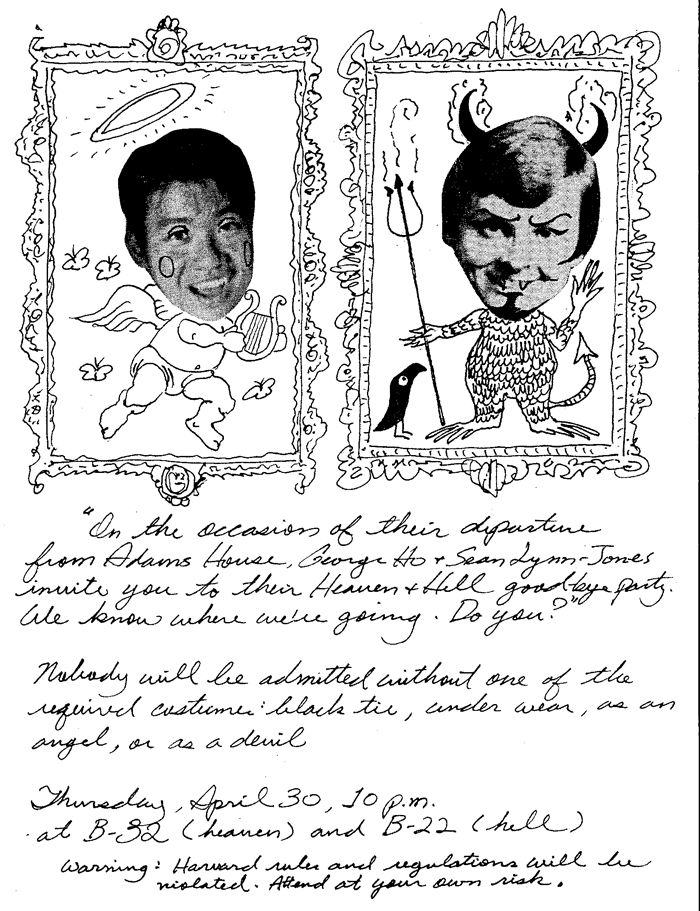

In the spring of 1992, George Ho and I hosted a “Heaven and Hell” party that turned out to be our last B-entry party. We used both our suites, with mine serving as hell and George’s (B-32—one flight up) serving as heaven. It was easy to assemble a party tape of heavy metal favorites such as “Hell’s Bells” and “Highway to Hell” to play in B-22. (We resisted the temptation to play “Stairway to Heaven” on the stairs from the second to the third floor of B-entry.) I wore a Satan mask and a tuxedo and served devil’s food cake, hellishly spicy dishes, and Devil Dogs. George served angel food cake and used dry ice to create knee-high clouds in “heaven.” It looked beautiful, but it was so cold that guests often fled to the warmth of hell.

All of these parties probably exceeded the budget allotted to each tutor for entry parties. Victoria Macy, assistant to the masters, somehow never failed to find a way to reimburse us fully for our expenses. I’m still not quite sure how she did that—and reimbursed us for the cost of all the alcohol we served—but I thank Vicki for quietly making all of our parties possible. I hope the Adamsians who attended them enjoyed them at least as much as my fellow tutors and I enjoyed hosting them.

Moving Out and Moving On

During 1991–92, my eighth year in Adams House, I decided it was time to leave. Adams had offered a comfortable refuge from the “real world” and a chance to meet a fascinating array of students. It sustained and supported me when a long-term relationship ended and short-term ones fizzled. But I had to move on. With the advent of the assignment of students to houses by a process of non-ordered choice and rumors that full-fledged randomization would be the next step, I realized that the Adams House I had known and loved was on the verge of irrevocable change. At least as important, I had become aware of the disconcerting fact that each year all the students in the House remained the same age (on average) while I grew progressively older. I also had a general sense that it was time to “cut the umbilical cord,” as I think Master Kiely put it, and head out into the adult world beyond Adams House.

At the 1992 Adams House commencement ceremony, I was moved when Bob Kiely marked my departure from the house by reminiscing about my contributions to Adams: “Sean is an institution within an institution. His rooms have the old world patina of an Oxford Don’s suite and his parties the culinary sumptuousness of a Salzburg cafe. Sean has been a source of continuity, stability, dry humor, and wise counsel to many at Adams House.”

John H. Finley, IV ‘92 helped me find a house on the coast in York Harbor, Maine, that I could rent from one of his relatives. I spent almost a year living there in solitude, enjoying the sound of waves crashing against the rocks outside the house. I moved back to Boston in 1993, and within a few short years I got married, had a daughter, and moved into a Victorian brick townhouse in Brookline, Massachusetts that’s both house and home – but this time, with a small H, and that’s just how it should be.