Back in April I had the privilege of sitting down with my friend Merle Bicknell, Assistant Dean for Physical Resources, and the architects of Beyer Blinder Belle, the visionaries who will be shepherding Adams House through the Renewal Project. I’m guessing (strike that, I know) that Merle had some trepidation about the meeting, because I have been a very vocal critic of the restoration work that has gone on at Quincy and Dunster over the past few years, having bent her ear on the subject over many occasions. I wanted to make sure that the architects understood that we consider Adams to be a sacred space and not to be lightly trifled with. On that account, I needn’t have worried, as the architects have done their homework. I’ll let the accompanying photo essay speak for itself. The excellent captions were supplied by architect Nate Rogers (who thankfully is a Harvard College graduate, something I would have considered a sine qua non for the earlier restorations, but alas no).

Rather than supplementing his comments, I will focus on some of the important takeaways from our meeting, which are not apparent from the illustrations.

The most important thing to understand about House Renewal is that fire safety codes have changed drastically since Adams was last renovated in the ’80s. Fire escapes are no longer considered viable egress, for instance, and if a building is to receive renovations above a very modest threshold, rooms need to be provided with two means of internal exit.

The second major factor is the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) which mandates that all portions of new-built or newly renovated structures be made fully accessible. Few of us without mobility issues have given much thought to the fact, for instance, that to enter the Dining Hall from the main Adams entrance requires negociating three separate stair sets. Accessibility will need to be addressed throughout the renovations, and like the fire code, will force certain solutions.

The second major factor is the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) which mandates that all portions of new-built or newly renovated structures be made fully accessible. Few of us without mobility issues have given much thought to the fact, for instance, that to enter the Dining Hall from the main Adams entrance requires negociating three separate stair sets. Accessibility will need to be addressed throughout the renovations, and like the fire code, will force certain solutions.

So here is a short summary of the proposed renovations, building by building:

Claverly Hall

Clavery (1893) is fortunate in that its horizontal floor plan already provides for decent accessibility throughout the building. The current suite layout will remain essentially the same, with installation of two new elevators and an additional fire exit at the base of the current main stairs. Of course, there will be entirely new systems – plumbing, lighting, heating, and electrical throughout. (The same is true for all the other buildings, including the much-awaited installation of AC in all public rooms.) Major changes come to the back of the ground floor, which is currently something of a rat-warren of rooms occupied by various clubs, and includes the old Clavery tank, or pool. These are scheduled to be reworked to feature an elegant set of multi-function spaces. A new entrance will also be provided to provide quicker access across Linden Street to Randolph Hall.

Randolph Hall

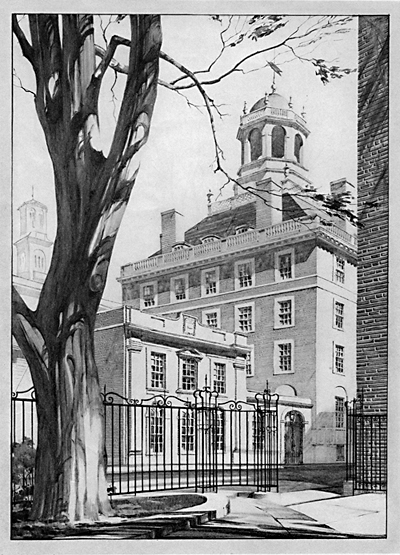

Randolph (1897) is the most complicated of all Adams’ buildings from a renovation perspective because of its ornate Flemish Revival architecture and vertical entryways. While the ground floor and Mt Auburn grand staircase will remain essentially unchanged, the upper floors will undergo considerable renovations that will largely reconfigure the layout of the existing suites. Current plans call for the preservation of the unique elliptical staircases, but would insert horizontal corridors along the interior walls of the courtyard to provide equal access to rooms. Space thus lost will be partially reclaimed by the removal of internal flue structures (as will happen everywhere) and the rerouting of current plumbing and electrical lines. To date, precise plans for this work have not been publicly released.

C-Entry, Common Rooms and Library

The C-entry building (New Russell), which was a last-minute add-on in 1932, will be completely reworked. While the main entrance will be carefully preserved, the existing dormitory spaces will be reconfigured to provide new dining, office and housing space. The Lower and Upper Common Rooms, Gold Room and Library from 1931 will be restored and provided with much needed service updates. A new elevator built into the current conservatory space will service these areas for the first time.

The Dining Hall

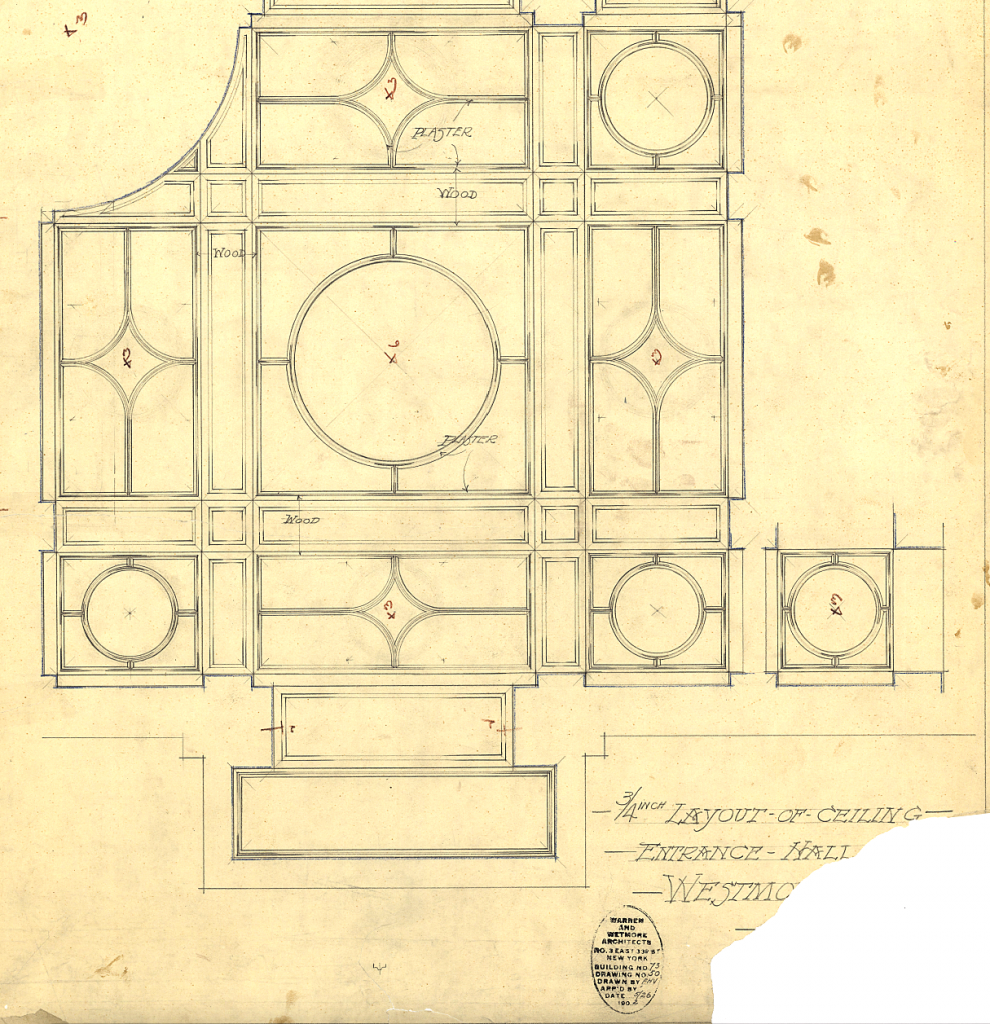

Perhaps the most remarkable of all the proposed changes come to the 1931 Dining Hall, which will receive an entirely revised seating configuration. In addition to a brand new servery and food prep area, the small dining room, which was formerly a coat room and a latrine, will return to those functions, and additional seating in the main space will be gained by glassing the current garden space, converting the large west facing windows into French doors, and merging the adjacent ground floor rooms in C-entry into a secondary dining area. (Full disclosure: I protested the loss of Adams’ only outdoor dining space and requested a re-thinking of how that roof might be made at least partially retractable. We are the only House that has nowhere to eat outside on a nice day.) The historic wood paneling and floors of the Dining Hall, much worn, will be restored to their 1930s glory, and the tacky ’70s lowered ceiling will be replaced with plaster. The light domes too, will be restored, but most interestingly, current plans call for the construction of a second floor above the Dining Hall, which will be accessed from Westmorly and the new Library elevator, and will serve as a new social/conference/meeting space. This new floor would not be visible from the dining area below and minimally visible from the street, the later due to set backs required by the Cambridge Historical Commission. These plans are still in the formulate stage and will require various regulatory approvals before construction.

Westmorly Court

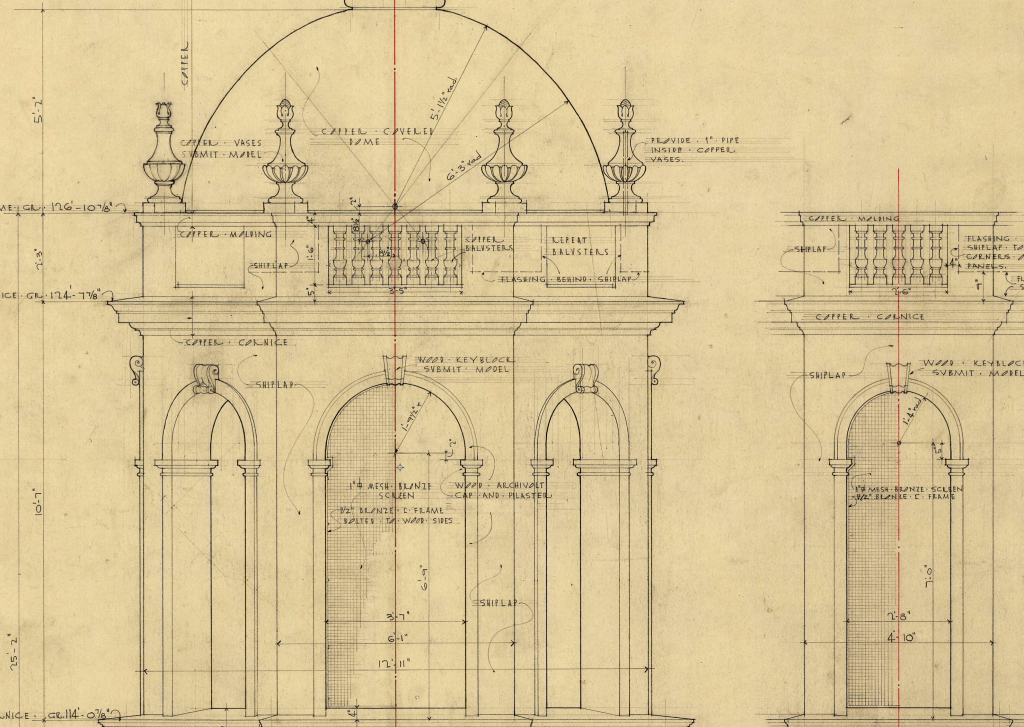

Westmorly, built between 1898 and 1902, presents similar problems to those of Randolph though less severe, as it already possesses a horizontal floor plan. However, due to fire safety and ADA restrictions, new linking hallways will be required on the upper floors that will essentially reconfigure existing suites on the west and east facades of the building. The FDR Suite, along with its beloved fireplace, will be carefully preserved, and the ghastly sprinkler system that now disfigures many of the rooms and hallways will be hidden. The pool theater is set for perhaps the most dramatic of makeovers, which are detailed in the photo essay. Again, these plans have not been finalized.

The Tunnels

At this point it is unclear how much of the tunnel artwork can be preserved. Current plans call for the photo documentation of all the tunnel panels before construction begins.

In Sum

The architects stressed again and again that throughout all Adams buildings, utmost effort will be exercised to preserve existing architectural features. Where it is impossible to preserve elements in situ, they will be reused in other parts of the buildings. I made the comment—and the architects concurred— that one of the things that makes Adams unique is that each of the buildings has a very distinct character, and it is essential that this distinctness be preserved. One of the criticisms voiced about the previous House restorations is that a heavy-handed modernist hotel style was utilized throughout, already appears passé and has no connection with Harvard. I was again assured that this will not be the case for Adams (and in all fairness, our renovation is the work of an entirely different architectural firm).

So there you have it, my fellow Adamsians. We are about to be launched into the sea of Renewal, albeit with some trepidation. Rest assured however that I and a group of interested Adams alumni , along with our Faculty Deans, and Dean Bicknell, will be monitoring the process and doing our utmost to guide the good ship Adams to a safe harbor.