The year 1944 was notable for various reasons: D-Day, Rome was liberated, the war in the Pacific was finally going well, FDR got re-elected for a fourth term, and although we didn’t know it at the time, the atom bomb was almost ready to be dropped. (Alas, the Red Sox, with Ted Williams now a Marine pilot, finished fourth; the hapless Boston Braves finished sixth.) 1944 was also the start of my connection with Harvard, a couple of weeks after the invasion of Normandy.

After attending public schools in my home town of Atlanta, I was shipped off “to finish”, and I spent my last two high school years at Mercersburg Academy in Pennsylvania. When senior year came around, I had only a vague idea of going to Harvard, known to me mainly for its football team and a world-famous astronomer, Harlow Shapley. My father, a successful adman, had no input in my decision; it was my best friend, Shaw Livermore, who talked me into applying. His dad had a Harvard degree; mine was a UPenn dropout. My grades had been only slightly better than average, but somehow, I got accepted. Maybe it was because the southern boy quota was unfilled, or maybe it was that that Harvard was scraping the barrel in those grim WW II years. Whatever the reason, I got lucky: I had not applied to any other university.

We began our Harvard experience in July of 1944. Harvard had changed to a three-semester year so that we and other undergraduates could graduate in two-and-a-half years, an interesting option for the many of us in the Class of ’48 who were too young to be drafted into the military. We could, if we wished, go sooner to work or start graduate school earlier — if we escaped the draft. Another switch was to put freshmen in either Adams or Lowell House since all the other River houses and all those in the Yard had been taken over by WW II military units: the V-12 (Navy college training program), the V-5 (Navy and Marine pilots), and the ASTP (Army Specialized Training Program). These programs included many 18-year-olds who would otherwise be drafted, plus some older fellows whom the military deemed officer material. There were around three thousand of them, roughly twice as many as civilian undergraduates. One was Robert F. Kennedy; another was “Crash” Davis, an ex-major leaguer who now coached my sport, baseball. (Later his name and career would be made famous by Kevin Costner in the movie “Bull Durham”.)

The luck of the draw put me in Adams House. The House secretary, Mrs. Dallas Hext, perpetually cheerful in spite of being a war widow, had assigned me to A-36, in those days a quad, with two lively roommates from Seattle, and my prep school buddy Shaw Livermore concentrating in history. I had long ago decided to be an astronomer — I had been a passionate amateur star-gazer — and as I explained to my roommates, I was primarily interested in the ABCs: Astronomy, Baseball and of course, Co-eds. At the time I was going steady with a local girl about to go off to Pembroke College (now integrated into Brown University).

In the next room was an exuberant Frenchman concentrating in mathematics who had bought an old upright piano and put thumbtacks in all the felt hammers to make it sound more like a spinet. Just down the hall lived a secretive fellow in his late 20’s who was studying Japanese, presumably sent to Harvard by the WW II equivalent of the CIA. Over in B-entry next to the FDR suite was a fellow astronomy concentrator. (At the time we were the only two in the College.) I rarely ventured much farther than C-entry with the dining hall, the Lower Common Room, the library and one or two piano practice rooms. For me, Westmorly Court was home. However, on occasion I met with my freshman adviser, a boozy, hard-bitten American who had lost a leg fighting fascists in Spain. He taught Spanish and now lived in G-entry. Why Harvard chose a language teacher to be my advisor is a mystery, and of course, he had me enroll in his beginning Spanish course, made entertaining by his occasional political outbursts. (“Benito Mussolini, el hijo de puta en su balcón!”)

The Astronomy Department, very much depleted by the war effort, was missing several of their best known professors. My beginning two courses in Astronomy were actually taught by a former adman and lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium, Charlie Federer, who recently had become the editor of Sky and Telescope magazine. His wife, Helen, taught the labs. We later became good friends.

The President of Harvard was an eminent physical chemist, James Bryant Conant, who had made, and would make, many changes in the University. Perhaps most importantly, his administration inaugurated the use of entrance exams, thereby eliminating the promise that if your dad was rich and went to Harvard, you were automatically admitted. Another innovation was the General Education Program which required students to take courses in three broad areas: natural sciences, social sciences and the humanities. (I still have nightmares that at time of graduation I lack one of the required courses.)

The Master of Adams House was the Secretary to the University, David Little, a kindly fellow with a prodigious memory for names. Time Magazine claimed he knew more alumni by first name than any other man alive. At our first, and I think our only face-to-face meeting, he surprised me by addressing me by my nickname, Red.

Because of the war, life in the House was rather austere and our food rationing cards had been collected at registration to be used by the dining hall. Meat was in short supply as were dairy products like butter, cheese and ice cream. Still, Adams had, according to the Harvard Crimson, the best food of any House. There were other benefits of residency. Because of Adams’ dozen or so unguarded gates, there was a constant challenge to the strict parietal rules intended to keep naughty girls from “visiting” us after hours. And it had the only House swimming pool.

Perhaps because of the general instability of college life at the time, Adams had not yet achieved the reputation of the “artsy House”, and many of us were just marking time until we turned 18 and got drafted. My turn came in July of 1945 and I spent 11 months of the dwindling days of WW II in the Chicago area enrolled in the Navy’s Radio Technician program. (The atom bombs were dropped and the war ended while I was still in boot camp.)

When I returned to Harvard in September of 1946, Mrs. Hext had, for reasons unknown, assigned me with two of my former roommates to F-2 where I continued until graduation in June 1949. We were now, on the average, older and more mature following our time spent in the military. And many of us were there thanks to the G.I. Bill which paid not only tuition but also for books and essential school supplies. (It mattered not in which university you were enrolled; if you were admitted, the G.I. Bill paid.) As a result, a Harvard education became possible for many students from various socioeconomic backgrounds. In the next suite were two exceptional guys, Harold May and Clifton Wharton, both Afro-Americans, and we quickly jimmied the lock on the door separating the two suites. Not only did we all greatly enjoy and appreciate the greater diversity in all our backgrounds, but the semi-secret connecting doorway made it possible for one of my roommates, who seemed to have a new girl friend every month, to quickly shuttle his current lady friend into the other suite if the House superintendent came a-knocking unexpectedly. (Years later Clif became, first, President of Michigan State University and then Chancellor of the entire SUNY system. Harold was the cox of the varsity crew and now practices medicine in Boston. He also had 12 years of residency in rural Haiti at the Albert Schweizer Hospital.)

Even though I was spending more time up on the hill in the Astronomy Department, I continued to be active in Adams House life, especially in matters of house sports and music. One classmate and house member, Joe Blundon, had formed a square dance band, and one of my roommates (on banjo) and I (guitar) would occasionally pick up $25 a gig playing for local college alumni groups and VFW parties. I also remember good times playing jazz piano duets with Clif Wharton on WHRV, the Harvard radio station that would later become WHRB. He also taught me how to jitterbug.

I soon had almost enough credits to concentrate in music, and together with my Radcliffe girl friend, Elizabeth Menzel, a talented violinist and music enthusiast, we took in concerts and participated with music groups around town. It was here and now that I began a new avocation: building musical instruments. My first construction was a crude bass fiddle, made of plywood and 2×4’s, for a small symphony orchestra up at the Observatory, but later I became more serious and started building a clavichord just because I was into — and still am — baroque and pre-baroque music. It’s sitting here in my studio even as I write this.

In many ways, those were the good old days. As I have noted, students generally were more mature and serious about their studies (but still left ample time for the usual recreational activities). Many (most?) of us never bothered to lock our doors (and rarely suffered robberies), the war was over, and Ted Williams was back. As for me, I was now happily doing real astronomical research (analyzing radar blips from meteors), and had an honors thesis underway.

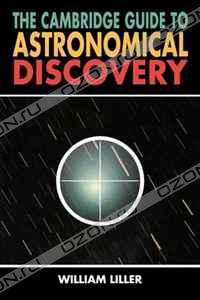

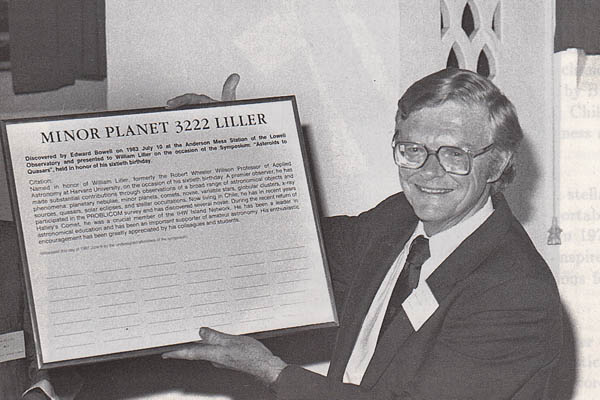

For me, because of my hitch in the Navy, graduation came a year late, in 1949, and I left to pursue graduate studies at the University of Michigan, said by some to be the “Harvard of the mid-west”. But eleven years later, now with a PhD, a reputation as a pretty fair teacher, and several well-received research papers, I returned to the real Harvard, having been made offers that I couldn’t resist: a full professorship and the Departmental chairmanship and later, the Robert Wheeler Willson Chair of Applied Astronomy. Within a few short months, I was back to going to Apthorp House Friday teas and the regular science lunches, first as a non-resident tutor and soon as a House Associate.

Then in 1968, totally out of the blue, I was asked by President Nathan Pusey ’28 to become Master of Adams House, succeeding Reuben Brower, the beloved English professor who had been Master for thirteen years. I suppose that President Pusey got my name from the Dean of the College, Fred Glimp ’50 whom I had known since undergraduate days when we played together on Harvard’s baseball team. But the offer came as a total surprise, although, of course, Adams House was very much an active part of my life.

And so, in the summer of 1968, with Dallas Hext still — after 25 years — worrying about the nuts and bolts of the House, I moved into Apthorp House with my wife Martha Hazen, a former student of mine from Michigan, and our two young children, John and Hilary. Although the concept of “co-Masters” was still not officially recognized, Martha was very much involved in House activities, advising me on many matters and charming the House staff members and those students who attended the Friday teas. You can see her and the kids in action in an Esquire Magazine article about the Apthorp teas entitled “You Wouldn’t Mind a Little Class, September 1972.

Adams was by now solidly established as the artsy house thanks primarily, no doubt, to having had for many years a Professor of English as Master. To have now a relatively young (41 years old) astronomer as Master signaled (alarmed?) some that all that would change. However, from the start, I vowed that I would support in any way I could the continuation of the arts, for example, by ear-marking a goodly portion of the House budget for the Music, Art and Theater Society activities.

Then came the shattering events of April 9, 1969 with the forced occupation of University Hall by several hundred students (not all from Harvard) who were opposed, among other things, to the presence of the ROTC on campus. After a rather violent response from the Cambridge police called in by President Pusey to oust them, the University atmosphere continued to be tense fueled also by the unpopular war in Vietnam. The following week, there was a call by protesting students for a strike, and at a meeting attended by some 12 thousand students and faculty (in the Harvard stadium), it was narrowly voted in favor, and for the first time in its history, Harvard was on strike — for three days.

Adams House, being closest to the Yard and Harvard Square, became a convenient meeting place for agitators, and despite complaints from many of the House residents — and the Master — the Lower Common Room was, on several occasions, taken over by movement leaders for meetings meant to organize further demonstrations. The House Committee by, I suspect, a slim majority, had decided that the Common Room was indeed a common room, and so as long as at least one House member was involved and played host, the meetings could take place. Subsequently, at least to some, and particularly to one visiting B.U. coed, I became known as the “radical, hippie Master”. To be sure, I was one of the more liberal of the Masters at the time, but I was hardly “hippie”, and in fact, many faculty were far more radical than I.

The Students for a Democratic Society, the SDS, became increasingly active and militant even, some charge, setting fire to the ROTC building. One small group, led by an ex-Columbia student King Collins, would invite themselves into various students’ quarters where they would stay for a few nights before moving on. Adams House was not spared, but after a couple of nights, several burly House football players peacefully persuaded the group to take up residence elsewhere. “This has become a bad scene,” Collins was quoted as declaring. Around the same time, according to the Harvard Crimson (4/15/74), “three of Collins’s friends took off their clothes and washed them in the Eliot House laundry room, before a crowd of interested onlookers. When Alan Heimert, Eliot’s master, asked one of the three if he had ‘some kind of masculinity problem,’ the man pulled a cigarette from Heimert’s mouth. ’Fuck off,’ he explained. Collins went back to disrupting classes.”

The ROTC had been and continued to be one of the main topics of discussion at Harvard — and elsewhere in the Ivies. The faculty and various faculty-student groups held numerous meetings to argue the future of the ROTC which had been a Harvard presence since 1916. During the Korean War, 1950 -53, according to President Conant, 40 per cent of the undergraduates were enrolled in the ROTC receiving financial support of one sort or another. And in the months before the occupation of University Hall, the faculty were already debating its future. But by mid-1971, ROTC was effectively banished from the University.

During these difficult years, many important changes were taking place in the University administration. Derek Bok, formerly Dean of the Law School, succeeded Pusey as President in 1972, and Martina Horner, a Social Relations professor, replaced Mary Bunting at the head of Radcliffe. John Dunlop, a professor of Economics and a highly successful Washington labor negotiator, took over the University Deanship from Franklin Ford. The History Department’s Ernest May was Dean of the College, 1969-71, and he was then succeeded Charles P. Whitlock, who served until 1976. Both Bok and May I knew as neighbors in Belmont, and I felt confident that they could successfully steer Harvard through these difficult times. And Dunlap quickly became one of my most admired administrators as he awed me and others in his masterful handling of the problems of the times.

Meanwhile, back in Adams House, an ongoing hot topic of discussion was the possibility of the House becoming co-ed. During my undergraduate days, Radcliffe was another college almost entirely. Women were allowed to take some of the smaller undergraduate courses offered by Harvard, but the larger classes were split in two: one section for males, one for females. According to Wikipedia, back then, Radcliffe was the “coordinate college” for Harvard University. Formal merger was not signed until 1977, and full integration not until 1999. Even so, Radcliffe had by the late 60s become an ex-officio part of Harvard University

In the winter of 1969-70 I received a telephone call from the Master of Radcliffe’s South House, Professor Richard Baxter of the Law School. (South House was later renamed Cabot House in 1983.) And so began turning yet another wheel of change. Baxter told me that he had asked “his girls” in which House, if they had the choice, they would like to live. “Adams,” was their near-unanimous reply. I’m not sure if Baxter knew that I had already been campaigning for a mixed House, but we decided to send a proposal to President Pusey that would have, “on an experimental basis”, 25 female students from South House swap places with an equal number of Adams House men. Pusey had earlier let it be known to me and to others as well that he opposed integration, but now no doubt sensing that change was inevitable, he formed a committee chaired by psychology Professor Jerome Kagan to advise him. The committee subsequently voted overwhelmingly in favor of integrated housing, and during a bright and sunny weekend in February 1970, the swap was made. One by one the remaining men’s houses quickly followed suit.

That Adams House was now a better place, there can be no doubt. It seemed that everywhere, from the dining room to the common rooms, from the library to the Friday afternoon teas, the general ambiance, overall spirit and civil manners were improved. Life in the House had become more natural and relaxed, and the hateful parietal rules were out the window. Only one minor residual tension seemed to remain: the swimming pool, where before integration, dress or lack thereof had been optional. The student House Committee’s solution was to continue this rule — except for two hours in the morning when bathing suits were required. Some grumbling was heard but not for long. The only concern voiced by Dean May’s office was that proper sanitary conditions be maintained.

During these tense and often turbulent times, I was fortunate to get good, sound advice from both students and faculty. To name just a few, Charles Schumer, Adams House ’71 and later a Resident Tutor (and New York senator), discussed all sorts of matters with me at lunch on various occasions. Vernon Jordan, a Fellow at the Kennedy Institute and soon to become President of the National Urban League, resided in the House and advised me on the Black Studies issues. (He would often delight House members by referring to me as his “Massa”.) Once, when I wrote a letter to the New York Times supporting a black student’s rights, I received some unsigned hate mail. One asked simply, “Did you ever kiss a n—–‘s ass?” (hyphens not used in the letter). The student, Joseph Rhodes, a House member and Harvard Junior Fellow, had been arguing for a Department of Afro-American Studies. (The next year Joe was named by Time Magazine as one of the 200 new leaders of America. He subsequently served three terms as a Pennsylvania State Representative.)

And of course there were the indispensable Senior Tutors, first Robert Haney and then James Thomas, plus Assistant Senior Tutors Joseph Harris, Jackson Bryce and Fred Fox. All were frequently consulted as was a good friend Professor Jack Womack who could often be found in the FDR Suite, B-17, in those times a Tutors’ Study.

I tried to vary my own participation in House activities. That included music, performing with Fred Fox, he on oboe, I on harpsichord, at one of the annual Christmas parties (where I, of course, assumed the role of Christopher Robin in the traditional reading of “Winnie the Pooh”). Charles Bernstein ’72 put on a highly successful and entertaining production of Peter Weiss’s “Marat/Sade”, staged in the Dining Hall, with me taking (naturally) the role of the Master of the insane asylum. And noting that I had been a catcher back in my undergraduate days, the House baseball team called me up out of retirement (at the age of 46 !) to catch for the House team: I’m intensely proud to say that we made it to the finals, losing a close one to the mighty Eliot House nine. Also, our House softball team, with Professor Mark Ptashne pitching and me at shortstop, demolished the Harvard Crimson, although the paper reported erroneously, as they always did back in those days, that they had won, 23-2.

Back in 1968, Harlow Shapley, one of my senior colleagues at the Harvard Observatory, had warned me that the dual careers of House Master and research astronomer would ultimately result in my becoming a has-been in the rapidly-evolving latter profession. And so, taking heed of this warning, I decided to terminate my Mastership and get back to full-time astronomy. After all, for my entire life I had been enamored with the cosmos. And so in 1973 when Derek Bok asked me if I wanted to continue, I decided to pass the pleasure on to my friend Bob Kiely, yet another English Professor who would surely see to it that Adams House remained healthy, happy and artsy. And Dallas Hext would be there ready to assist him.

Later still, in 1981, I decided that professionally, I really needed a change. I had been going once or twice a year to Chile to use the new, big telescopes that were sprouting up in the clear, dry climate there. At the same time, for personal reasons, my marriage was coming apart. And so when a tempting offer came for me to become Associate Director of an established Chilean astronomy center, I pulled up stakes and moved to the oceanside city of Viña del Mar. Several years later, I re-married and, well, here I am. It’s been thirty years now, and even though I’m doubly widowed, I continue happy, living with a Chilena who is not only a very dear friend but also an excellent caregiver. This year I’ll be 84, and my health is holding up quite well enough for me to continue getting out to my little NASA-supplied telescope in the back yard to look for comets, novas and other things that pop up unannounced in the night. I’ve now got about five dozen discoveries to my credit.