A couple months ago, I received a call from a very courteous gentlemen in Santa Fe, inquiring whether or not I might want to buy an old, wooden sign. But not just any sign: An old “Adams House sign,” the caller said. “It dates to about the time of the Civil War, and originally came from Boston.” Oh, my ears perked up immediately, as I had once seen a faded old letter in the House archives a few years back…now if I could just remember the specifics… But perhaps I should tell you the story from the beginning.

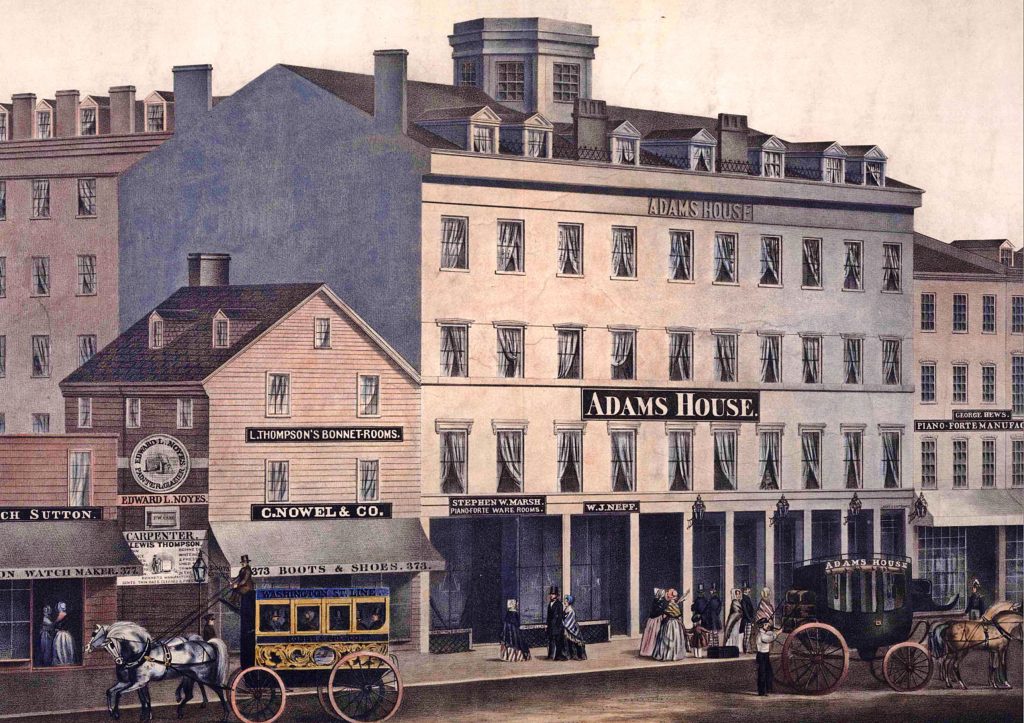

You see, before there was Adams House, there was the Adams House, one of Boston’s earliest luxury hotels. Opened in 1846 on the Washington-Street site of the historic Lamb Tavern, The Adams House Hotel possessed a stern Federal stone facade — and, critical to our story — a large wooden sign above the main entrance. Later expanded with an annex in the 1850s (which still stands on Washington Street) the original structure was replaced with a much larger Victorian edifice in 1883 (now demolished).

In 1889, King’s Hand-Book of Boston noted that the Adams House was “one of the finest and best-equipped hotels in the city, of which its dining-rooms and café are … conspicuous features.”

By the early 1900s, however, the Adams House clientele began to change, with short-term guests ceding way to local politicians and businessmen looking to secure cheap extended lodging near the Statehouse. Calvin Coolidge, notorious for his frugality, took a room at the Adams House for $1 per day in 1906 as a new member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. In an unusual display of extravagance a day after being elected governor in 1919, he expanded his digs at the Adams House to a two-room suite with bath on the third floor for $3.50 per diem. Coolidge was at the Adams House when he received the telephone call informing him of his nomination as Warren G. Harding’s vice presidential running mate in 1920.

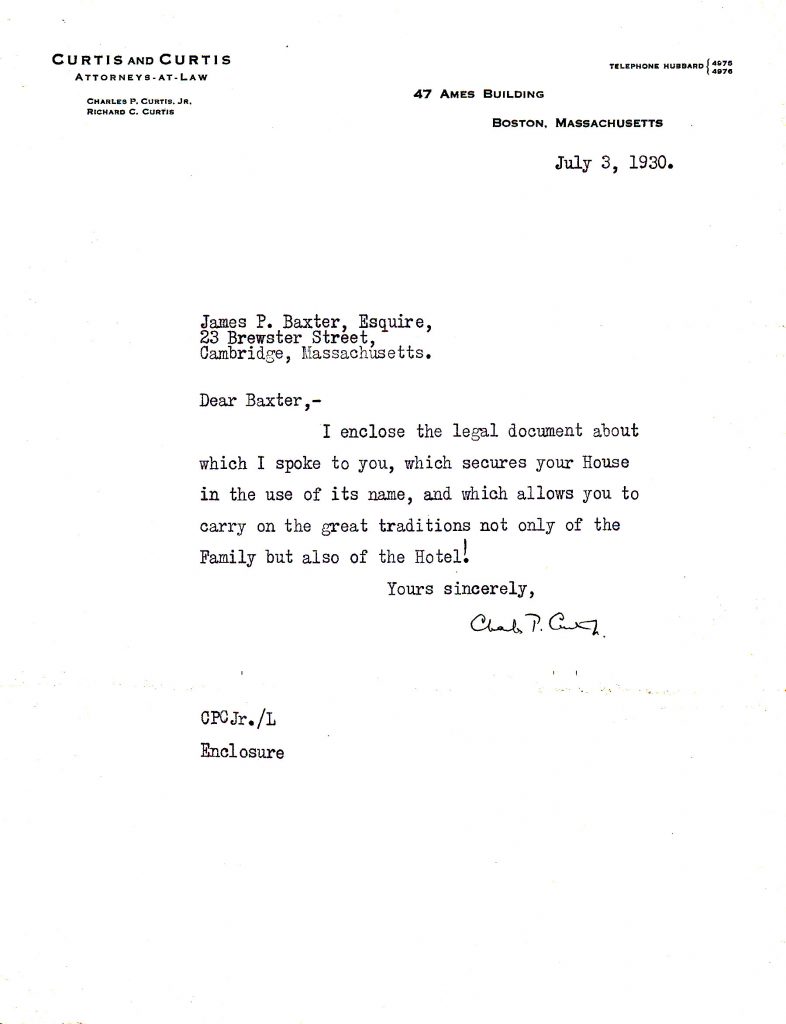

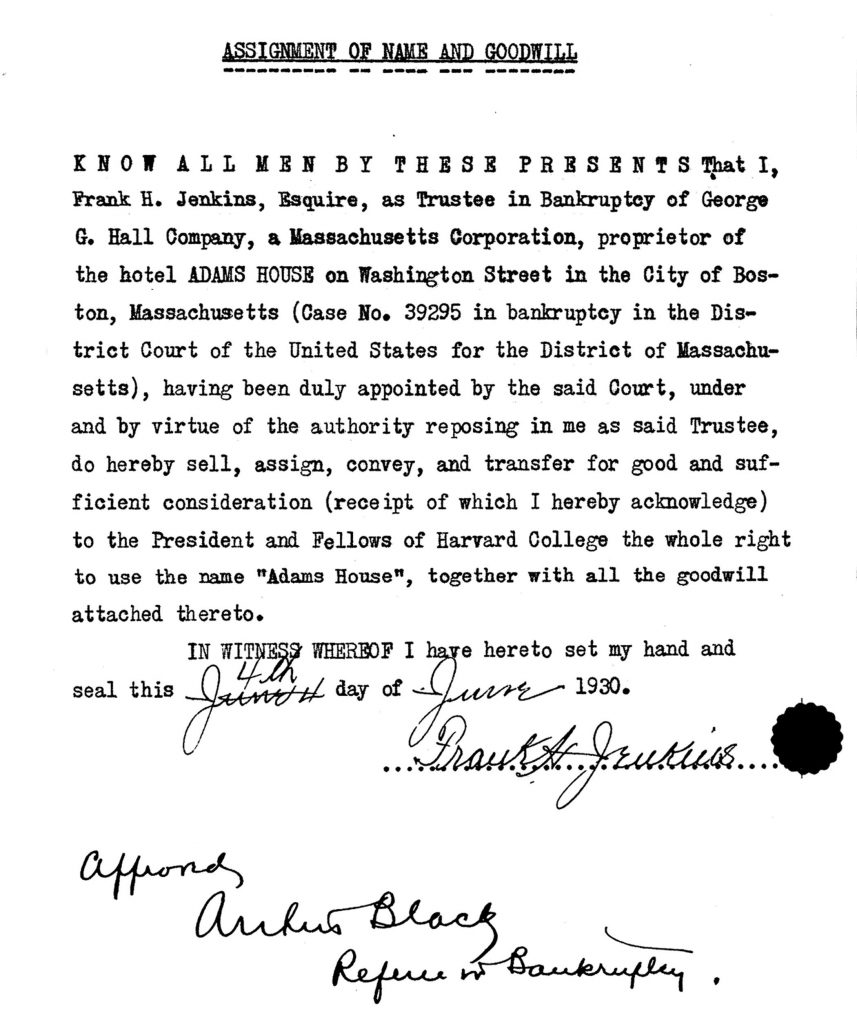

The Adams House Hotel fell victim to declining revenues during Prohibition (deprived of the income from all those hard-drinking politicians and newsmen) and was closed in 1927. The main building was demolished in 1931. In 1930, Harvard, anxious to name one of its new Houses after the Adams family, acquired the name and goodwill from the bankrupt establishment as a legal precaution. That signed contract was the document I had remembered from the archives all those years ago, addressed to Professor James Baxter, who would shortly become the first Master of the new Adams House:

So of course I was interested in the sign! Pictures and descriptions flew back and forth as price negotiations got underway.

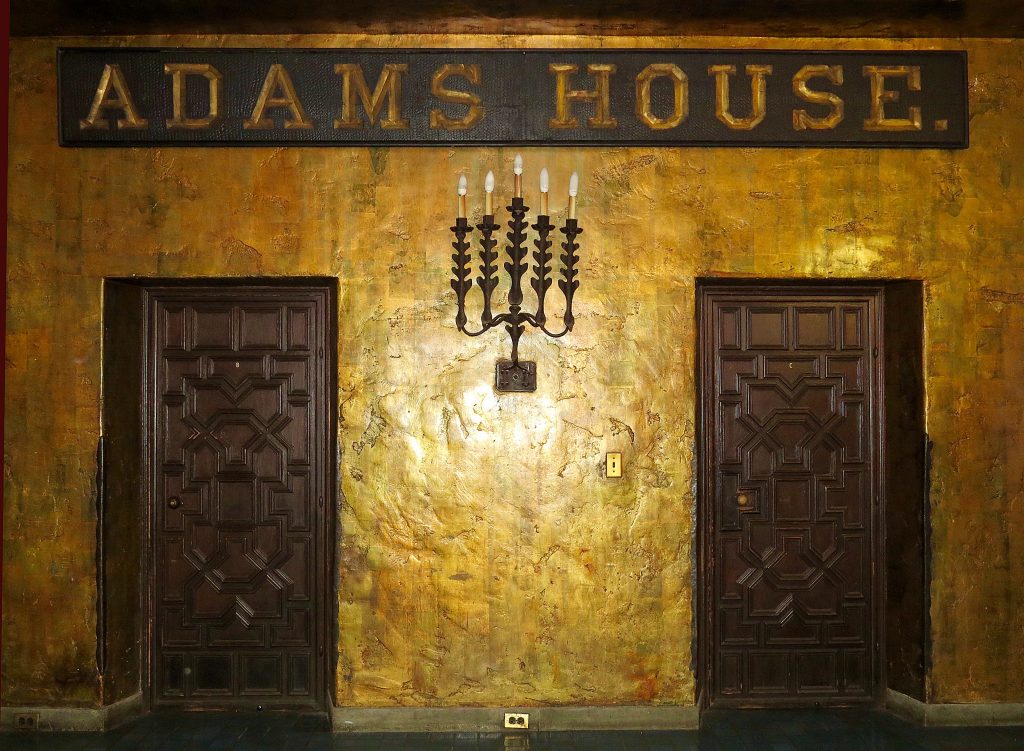

Based on typography and construction, the sign almost certainly dates from the 1846 iteration of the Adams House Hotel. (Whether it’s the sign you can see in the 1848 lithograph above we don’t know, but it looks almost identical, and the size and scale are an excellent match. The only real difference is that the sign in the illustration has raised capitals, but that might be artistic license. Regardless, this particular lettering style fell from fashion after the Civil War, so the sign most likely predates the 1882 Victorian incarnation.) The 18″ letters are gilt with paint, hand-carved into a single pine plank 2” thick, 2′ wide, and 16’ long, which weighs close to 80 pounds! The entire black background was then hand-chiseled to produce a rippled effect (click the picture below to enlarge). This was not an inexpensive sign, then or now. Though the exact provenance can’t be proven, a reasonable guess would be that the original hotel sign was retained as a showpiece when the first structure was demolished in 1882, and then later dispersed with the goods of the hotel during bankruptcy in the 30s. By the 1950s, the sign was documented in the hands of a Boston antiques dealer, who sold it to the mother of my caller, who also owned an antique shop — in fact, she named the business Adams House Antiques, where the sign remained over her Santa Fe door until she decided to retire this past year.

Long story short: a mutual price was agreed, the item shipped, and then I took a month or so to gently restore the sign, mending it back into its original single piece frame. Given its age, the sign’s condition is remarkable, no doubt due in part to the many decades spent in the humidity-free desert Southwest.

Here’s how it looks hanging in the Gold Room entrance to the dining hall:

So, a small piece of the first Adams House returns to its legal successor, the second Adams House, after one hundred-seventy years. A neat bit of cyclical history, don’t you think?