Out of nowhere a few months ago, I became curious to learn who had occupied the FDR Suite after Franklin and Lathrop left in June of 1904. My faithful colleagues made the trek over to the depths of Widener to consult the Harvard Directories, and lo and behold, imagine our surprise to learn that it was none other than the library’s namesake!

Yes, that Widener, Harry, of library and Titanic fame, moved into the Suite his sophomore year and stayed two years. His roommate during that period was Edward Clarkson Potter Jr, whose main claim to fame seems to be he left Harvard his sophomore year to marry a woman 9 years his elder. (They divorced in 1921 after he was caught in flagrante with another woman. Rather sad to have your life reduced to such a footnote!)

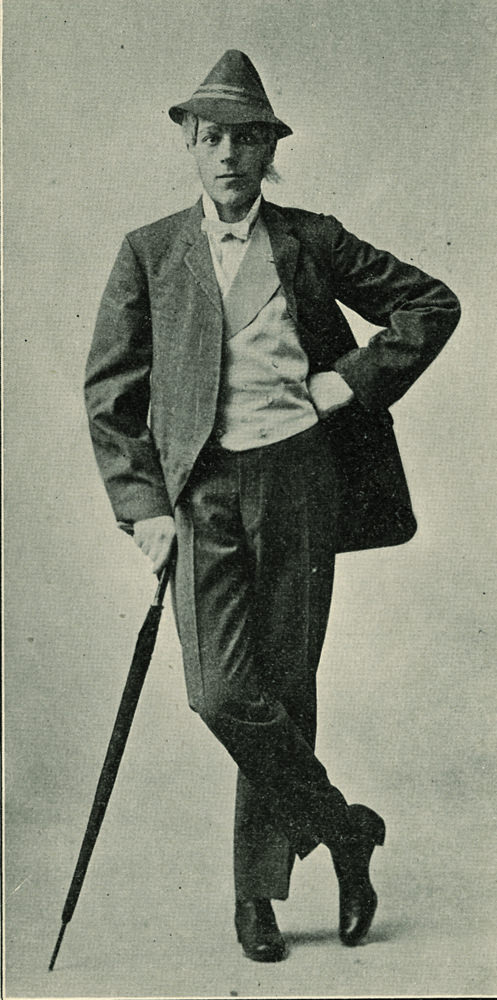

Harry Elkins Widener in costume for the Lotus Eaters

Harry Elkins Widener’s bio, despite his Harvard prominence, is barely better fleshed out. Stand any warm afternoon on the steps of Widener, and you will hear the tour guides tell you that he was born in 1885 into an immensely wealthy family that controlled the streetcar interest in Philadelphia, along with large holdings in steel and railroads. He attended the Hill School and then entered Harvard’s class of 1907. While at Harvard he was a member of the Owl and Hasty Pudding Club, and it was through the latter—so the story goes—that he became interested in period costume design while doing research for the 1907 production, the Lotus Eaters. Again, according to the tale, this led to a love of old books, and within a few years he had pieced together a world-class collection of rare volumes. Harry was in fact returning from a book-purchasing trip to Europe when he and his parents made the fateful decision to sail on the maiden voyage of the Titanic. His mother and maid survived. Harry, his father, and his father’s valet drowned. (At the last moment, Harry is reported to have returned to his cabin to rescue a first edition of Bacon’s Essays, which he had just purchased in London.)

Yet something always seemed odd to me about the Lotus-Eater costume story. How in just five short years do you go from researching costumes to creating a world-renowned book collection that becomes the nucleus of one of the largest libraries in the world?

It turns out there is a powerful character largely missing from the story, one that provided the spark—and perhaps even the passion—to initiate such a collecting frenzy, and that person is A.S.W. Rosenbach. (For this connection, I am deeply indebted to Leslie Morris’s “Harry Elkins Widener and A.S.W. Rosenbach: Of Books and Friendship;” Harvard Library Bulletin NS 6, no. 4: 7–28.)

Abraham Simon Wolf Rosenbach was born in 1876 to a successful dry goods merchant, the youngest of seven children. He was a shy child, and spent much of his youth with Moses Pollack, his maternal uncle and an antiquarian book seller. Through time spent at his uncle’s store, he became a dedicated bibliophile, and entered the University of Pennsylvania. With the support of his mother and siblings, he stayed on to complete his doctorate in Elizabethan and Jacobean literature in 1901.

With Uncle Moses set to retire, and another brother eager to start a new business, A.S.W. (or the Doctor as he became commonly known) decided to form the Rosenbach Company to sell antiques, rare books and manuscripts. This new venture was supported in part by Uncle Moses’ hoarded treasures, as well as by the sale—on consignment—of the rare book collection of wealthy Philadelphian Clarence S. Bemmet, who had been a valued customer of Uncle Moses. It was likely through Bemmet that the Doctor was introduced to young Harry during Christmas vacation at the Wideners’ 110-room estate, Lynnewood Hall. Harry had made his first major purchase just a few months earlier: an illustrated third edition of Oliver Twist. (The book cost $200, which at the time, was more than half a year’s tuition at Harvard.) As Morris notes: “Dr. Rosenbach was not much older than Harry, so it seems natural that a mutual enthusiasm for books and literature should develop not only into a business relationship, but a friendship as well.”

Eleanor Elkins Widener

What the precise nature of the friendship between these two retiring young men was, we will never know, but it was close. It seems fairly obvious that Harry’s personal papers were highly “curated” after his death by his mother, and Rosenbach, who remained in the employ of the Wideners, had no incentive to share details either. We DO know though that the Doctor never married, and lived for the rest of his life in a Delancey Square townhouse with his brother. Harry too seemingly showed no interest in marriage. He was 27 when he died, which was well on the way to confirmed bachelorhood in those days.

What is clear however is that Rosenbach was the perfect salesman: credentialed, charming, and very persuasive. Soon the Wideners were purchasing quantities of books totaling astronomical sums from his new firm. Mrs. Widener, who doted on her eldest son, showered Harry with gifts. Just a few weeks after the fateful Christmas introduction, the following January as a birthday present he received $18,000 worth of color-plated books for his collection. It is entirely likely that some of this hoard landed in the FDR Suite, at least for a time. This level of gifting went on throughout his years at Harvard and beyond. (To give you some idea of the astonishing immensity of this amount, $18K in 1907 had the equivalent purchasing power of $500K today.)

After graduation, Harry supplemented his mother’s extraordinary giving with major purchases of his own, spending hundreds of thousands of dollars with Rosenbach and other firms to form his collection. Through it all the Doctor was there as friend, mentor and guide. The Doctor was also engaged to write the official catalogue of his collection, a handsomely bound copy of which made its way to another celebrated bachelor, Archibald Cary Coolidge at Harvard.

(Coolidge, who built Randolph, and who would later become the first University Librarian, made the huge faux pas of writing Harry to congratulate him on his father’s collection, an error he quickly corrected in a subsequent communication.)

Francis David Millet, painted in Paris while a war correspondent during the Russo-Turkish war of 1877, courtesy National Portrait Gallery

Fast forward to the last night on the Titanic. We know from survivors’ accounts that after attending a private dinner hosted by his mother in honor of Captain Smith, Harry retired up to the smoking room for a game of cards. His companions at the table were Harvardian Frank Millet ‘69, the American artist, author, reporter, painter, sculptor, muralist and at that moment, president of the American Academy of Rome. Also present was Major Archie Butt, Millet’s travelling companion, and an important aide to President Taft. Whenever Millet was in Washington, these two gentlemen lived together and were deemed inseparable companions. Millet was in fact married with children (all conveniently parked in England), but had had a well-documented romance with artist Charles Warren Stoddard while a studying art in Italy in the 1870s. For his part, Archie was a confirmed bachelor, who was inordinately devoted to his mother. Fortunately, the smoking room was still mostly an all-male preserve in 1912, and the three had retired there to avoid having to deal with “obnoxious, ostentatious American women, the scourge of anyplace they infest and worse on shipboard than anywhere” —this last a direct quote from Millet’s letter to his gay friend, the artist Alfred Parsons, posted just before the Titanic left Queenstown. (European women, it seems, escaped this opprobrium.)

Major Archibald Butt and President Taft

The card-playing coterie barely broke for the collision (“just an iceberg, nothing to worry about,”) nor did they seem much troubled as the smoking room emptied, and the call was made to swing out the lifeboats. Whether this was an incredible show of sangfroid, arrogance, stupidity, or a bit of all three is uncertain, but according to Hugh Brewster’s account in Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage, the game continued for almost a full hour, until the list in the now abandoned smoking room became so pronounced that the nervous steward finally urged the group to abandon the game and head to the boats. Such calculated acts of nonchalance seemed commonplace that night. As first-class passenger and author Helen Candee stood on an ever more sloping deck waiting for the boats to be lowered, she asked her companion “Why are we so calm?” “Because we are Anglo-Saxons,” came his dead-serious reply.

The sad truth is that if the members of the card party had taken the situation more seriously and just exited the starboard smoking-room door, they could have boarded one of the many boats that allowed men on that side of the ship. Instead, each reportedly returned to his cabin: Millet to place a warm vest knitted by his wife under his formal evening dress; Widener to retrieve his beloved volume of Bacon—and presumably, find his family—and Butt to fetch (or destroy) his diplomatic correspondence. (He may have been under some secret instructions from Taft while in Europe, a mystery that has never been fully resolved.)

The rest, as they say, is history.

Archie Butt’s body was never found. Nor was Harry’s, nor his father’s

Butt-Millet Memorial Fountain

But Frank Millet’s body was eventually discovered, held upright in the water by his lifebelt, head tilted back to the stars, still wearing the vest his wife had made for him. He is commemorated today by a bronze bust on the second floor of Widener (ignored by most on their way to the bathrooms, but a delight to those of us who can still read Latin) and by a truly unique memorial in Washington DC: a fountain on the ellipse across from the White House, erected to Butt and Millet by their friends in 1913. As the Washington Post recalled in Butt’s obituary: “The two men had a sympathy of mind which was most unusual.” A stylized figure with sword and shield represents Major Butt, another with palette and brush, Frank Millet—Damon and Pythias united forever in stone.

Eleanor Elkins Widener survived of course, but it was a closer call than most know. Some of the Titanic’s most prominent passengers—the Wideners, the Asters, the Thayers—had stuck together in a small group. Due to a confusion in orders, they had been held in agonizing limbo waiting for the launch of lifeboat number 4. When it was finally lowered just minutes before the end, Eleanor watched while Harry and husband George stood quietly by the rail—despite the fact that her boat descended to the sea with 33 open places.

The Doctor, ironically shipboard, probably in the 1930s

Though seemingly untroubled by the death of her husband (he is mentioned nowhere at Harvard) Eleanor was consumed by the loss her son (she was still delivering presents to his room the following Christmas.) Within months, she decided to act on Harry’s wish to memorialize his collection. (He had willed his books to his mother a few years before with the hope that “some provision” for them might be made for them at Harvard.) As Eleanor wrote to President Lowell: “My dear son Harry was a great admirer of yours & often spoke of the pleasure he had while in your classes. He loved Harvard & on our last voyage home, Mr. Frank Millet was a fellow passenger, & he & Harry would sit up very late talking of their love & ambition for the University.”

Indeed.

A.S.W. Rosenbach stayed on to guide Eleanor Widener on the construction of her memorial library. Though ubiquitously called Widener, she was wont to remind president Lowell that it was Elkins money, not Widener’s, that funded its almost 3 million dollar cost. Rosenbach also faithfully augmented Harry’s collection, diligently acquiring every single book on a wish-list Harry had made years before—paid for of course by Mrs. Widener, who spent $120,000 in one month of 1912 alone.

Theirs was a true labor of love. As Eleanor wrote to Rosenbach in July 1914: “When the library is finished, I want all the books installed there. Then I will feel happiness and know I have done as my dear boy wished. Over two years have gone since I lost him, and I am no more reconciled than I was at first, and never will be again. All joy of living left me on April 15, 1912. Forgive me for writing you like this, but you loved Harry, and can understand my sorrow.”

(Mrs. Widener seems to have quickly recovered some of her joie de vivre, as she married Alexander Hamilton Rice Jr. the very next year in 1915. She died while shopping in Paris in 1937.)

A.S.W. Rosenbach became one of the most successful antiquarian book dealers of his day, known as the “Terror of the Auction Room.” He remembered Harry fondly until his death in 1952.

As for our newly discovered Adamsian, well, we owe him a great deal. As Senator Henry Cabot Lodge noted at the dedication of Widener Library: “This noble gift of learning comes to us with the shadow of a great sorrow resting upon it…. It is a monument to a lover of books and in what more gracious guise than this can a man’s memory go down to a remote posterity? He is the benefactor and exemplar of a great host, for within that ample phrase all gather who have deep in their hearts the abiding love of books and literature.”

Well, that last sounds like us! So now we claim you, Harry, our bibliophilic host with the most!

Welcome to Adams House! Welcome home!