No part of Adams House evokes more fond memories from alumni than the swimming pool, which was closed in the early 1990s. The pool had been drained for years by 2007, but it was still the most popular topic in letters and emails from alumni on the occasion of the House’s 75th anniversary that year. Adamsians recalled “bacchanalian revels” and observed that the pool was “good not just for exercise but for entertainment.”

Such nostalgia is not surprising, because the pool was the most distinctive and famous feature of Adams House. It was exceptionally elegant and beautiful, a glorious and ornate link to the days of Harvard’s “Gold Coast.” As an amenity, it continued to set Adams apart from the other Houses that had been built after the Gold Coast era.

The pool would have been one of the highlights of Adams House for its architectural beauty and opulence alone, but it was even more famous for its tradition of nude swimming. Many alumni from the 1970s and 1980s have especially affectionate and vivid memories of coed skinny-dipping during the hours when the pool was officially open—and when it was supposed to be closed.

The pool was also the scene of several memorable artistic performances, particularly the 1978 production of Antony and Cleopatra that Peter Sellars ’80 directed. Unlike the nude swimming, this performance tradition continued after 1993 when the pool was drained and converted into a theatre.

In the Beginning: Creating the Westmorly Tank

The history of the Adams House pool is inextricably connected to the history of Harvard’s Gold Coast—a set of elegant private dormitories built around 1900 for Harvard undergraduates who wanted more comfortable accommodation than what was available in the antiquated dormitories of Harvard Yard, and who could pay handsomely for the privilege. For annual fees that ranged as high as $800, such students could enjoy modern conveniences and benefits such as central heating and hot water, plumbing, electricity, telephones, and swimming pools. The Westmorly Tank, as the pool was known initially, was one of the most prominent amenities of Westmorly Court, itself one of the most luxurious Gold Coast buildings.

The Roaring Gold Coast, 1910, the place-to-be at Harvard. From left to right: Apley Court, Claverly, Randolph, Old Russell (as distinguished from “New Russell”), C-entry (which stands there today), and Westmorly Court.

Westmorly was conceived by Charles Wetmore ’89, an 1892 graduate of Harvard Law School, who played a leading role in the construction of the private dormitories along Mount Auburn Street. He had built Claverly Hall (1892), the first of the grand private dormitories, and Apley Court (1897). Those buildings and other private dormitories attracted many Harvard students and were financially successful. Wetmore appears to have regarded Westmorly Court as an even more luxurious successor to his previous ventures. Westmorly was built in two phases. Westmorly South (the current B-entry) was constructed in 1898. Westmorly North (now A-entry) was not erected until 1902 – delayed until a necessary parcel of land could be acquired and while the City of Cambridge decided whether to widen Bow Street. The pool probably was always part of the plan for Westmorly, but it did not open for swimming until the fall of 1902.

While Westmorly Court was under construction, the New York architect Whitney Warren invited Wetmore to become his partner. Their firm, Warren and Wetmore, completed Westmorly Court. Its subsequent commissions included Grand Central Terminal, the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C., and the New York Central Building (now the Helmsley Building).

Warren and Wetmore designed their sumptuous Edwardian pool in a curious melange of the Tudoresque and Beaux-Arts styles. Located in an interior courtyard surrounded by Westmorly North and South, the pool chamber featured a vaulted ceiling with massive wooden beams and skylights that flooded the space with natural light. Twin curving iron-railed marble stairways led down to the pool from a door with stained-glass windows in Westmorly South, although the usual means of entry was through a far simpler passage from a door on the floor below. The wall at the far end was adorned with a colossal stone face of a river god. Water originally spouted from his mouth, but the plumbing was never terribly reliable, rendering the river god purely ornamental for extended periods. Massive, working fireplaces occupied two corners. The red brick walls featured large, arched windows, some covered with mirrors, and orginally, the south wall was trellised to suggest a garden setting. (Potted tropical plants and wicker furniture scattered here and there enhanced this effect.) The pool itself measured 27 by 45 feet. Lined with white tiles, it included a brass rail around four sides as a convenience for those who merely wished to float, or soak. There was a marble deck surrounding the pool, plus more marble in the shower that was added later in the far corner.

The Westmorly Tank About 1902. Note the dual seating areas with log fires ablaze for drying off; elaborate trellis; potted ferns, citrus and hanging baskets. This was the largest pool at Harvard when built and remained so until the construction of the Malkin Center (IAB) in the 1930s

For many years, Adamsians believed that the House pool had been built by the Vanderbilt family. In a 1963 letter to Adams Master Reuben Brower, however, Harold S. Vanderbilt ‘07 said that his family had nothing to do with the construction of Westmorly, although he had lived in the building for his junior year and his brother William K. Vanderbilt, Jr., lived there in 1898–99. Nevertheless, architect Whitney Warren was a cousin of the Vanderbilt family and a close friend of William K. Vanderbilt, Jr., which may explain the persistent rumor that the Vanderbilts built Westmorly and the pool.

The Westmorly Tank was not the only Gold Coast swimming pool. Claverly Hall featured a small pool. When Harvard History Professor Archibald Cary Coolidge added a gymnasium to his Gold Coast dormitory, Randolph Hall (later Adams House entries D–I), he included a pool in the basement, as well as courts for squash, racquets, and court tennis. These two pools were closed and drained decades ago, but traces remain in the basements of both buildings. Dunster Hall, a private dormitory that stood where Holyoke Center is now, had its own gymnasium complex with a pool, but this was converted to space for the Harvard Dramatic Club and eventually demolished. Craigie Hall (now the Chapman Arms apartments) also had a swimming pool. The Westmorly Tank thus was not unique, but it was always distinguished by its size and opulence. Of the five pools, only it remained a natatorium for almost a century after the heyday of the Gold Coast.

The Pool before Adams House

Harvard men likely swam nude in the Westmorly Tank from the day it opened. Although there seem to be no written records of this policy, swimsuits probably were regarded as unnecessary because only men used the pool (at least officially). During the first half of the twentieth century, male swimming without suits tended to be the norm in other pools, including those at YMCAs and schools. Nude swimming was considered to be more hygienic, and before the advent of closely-knit synthetic materials, it also prevented bathing-suit fibers from damaging the filtration mechanism. At Harvard, swimming tests and House swimming races were conducted without suits.

The pool seems to have had many and varied uses between its construction in 1902 and the incorporation of Westmorly into Adams House in the early 1930s. The Harvard swimming and diving team practiced and held tryouts in the pool, as did the water polo team. Some accounts reveal that there was a tradition of clothed, as well as unclothed dips in the pool. Donald Henderson Clarke, a Westmorly resident in the early 1900s, recalled in his autobiography, A Man of the World: “The pool was a handy bit of moisture into which to dunk unsuspecting and slightly alcoholized guests, without bothering to remove their clothing—often white tie and tails and a two-quart hat. This seemed to have a sobering effect.”

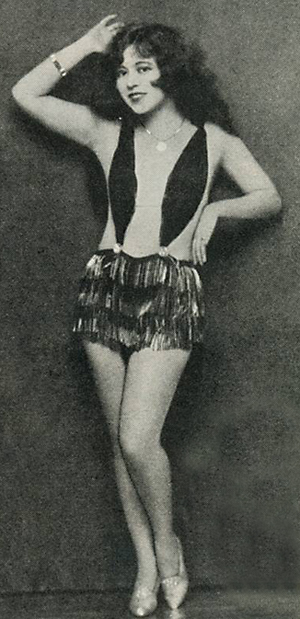

The daring, ever baring Ann Pennington

The most notorious episode in the early years of the pool was a purported swim by Ann Pennington, a dancer and actress who starred in the Ziegfeld Follies, Broadway shows, and silent movies between 1913 and the early 1940s. The term “sex symbol” may not have yet been invented, but Pennington was clearly an object of male fantasy in her day. Most of the stories about her aquatic adventure imply that the voluptuous Pennington swam nude, but it is unclear whether she swam alone, with other showgirls, or with Harvard men. It apparently did not take long for Pennington’s swim to become legendary. In Not to Eat, Not for Love, George Weller ‘29’s 1933 novel about Harvard life in the 1920s, a character says, “There’s a story about Ann Pennington and this pool, but no one seems to tell it the same way.” The Crimson in 1935 even claimed that Pennington “dedicated” the pool and pronounced it “the finest private pool in which she had ever swam.” As late as 1950, the Adams House entry in the Harvard yearbook continued to recount the tale of Pennington’s dip in the pool.

The Gold Coast era had ended by 1920. Under President A. Lawrence Lowell, Harvard countered the elitist appeal of the private dormitories by encouraging students to live in Harvard accommodations, renovating the Yard dormitories, and building its own modern residence halls, which were later incorporated into Winthrop, Kirkland, and Leverett Houses. Unable to compete with Harvard’s tax-exempt accommodations and facing an exodus of students during World War I, the owners of the Gold Coast dormitories sold their buildings to Harvard or converted them into apartments. Westmorly was purchased by Harvard in 1920. The February 25, 1920, New York Times proclaimed that “Harvard’s famous Gold Cost is no more” and that “the student body may enjoy what was the privilege of the few.” The Times noted that “swimming pools…instead of being reserved for a few wealthy students, have become part of the regular athletic equipment of the college.” The Westmorly Tank had been democratized.

In 1931, Westmorly Court and Randolph Hall were incorporated into Adams House. The Westmorly pool was not only retained but modernized with a new filtration and heating system for the benefit of the newly minted Adamsians. Having its own pool made the House more attractive to freshmen, who otherwise might have been drawn to the spanking new River Houses instead of the largely recycled buildings of Adams. In his 2000 memoir, A Life in the Twentieth Century: Innocent Beginnings, 1917–1950, historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., ‘38 claimed that: “I decided on Adams House…partly because Adams was the only one with its own swimming pool.” Crimson accounts and Harvard yearbooks from the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s suggest that the “famous” pool – the “pride and glory” of Adams House – received frequent use. It was just the place “to work off after-dinner lethargy. The heated water was soothing and the sound of the lapping of waves against tiles [was] peaceful,” declared the 1953 yearbook.

All Together Now: The Coming of Coeducation

When Radcliffe women first moved into Adams House in the spring semester of 1970, the survival of the tradition of nude swimming in the pool was suddenly in doubt. By and large, the transition to coeducational living generally went smoothly, but some students wondered if it was time to end nude swimming at Adams House. As William Liller, master of Adams in 1970, recounted in the June 2011 Gold Coaster: “Only one minor residual tension seemed to remain: the swimming pool, where before integration, dress or lack thereof had been optional. The student House Committee’s solution was to continue this rule—except for two hours in the morning when bathing suits were required. Some grumbling was heard but not for long. The only concern voiced by Dean [Ernest] May’s office was that proper sanitary conditions be maintained.”

Some swimmers availed themselves of the mandatory-swimsuit hours, but coed nude swimming quickly caught on. Men continued to swim without suits, and women often joined them in the pool. For many students, mixed nude bathing was a natural outgrowth of the social and political upheaval of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when a generation shed its inhibitions. One of the first Radcliffe women to move into Adams House, Marla Eby ’73, recalls that “it was the era of Woodstock, it was a different time.” In her memoir, Most Likely to Succeed: Six Women from Harvard and What Became of Them, Fran Schumer ’74 explains how the personal and the political were intertwined when women plunged into the pool: “It seemed more liberated to prance naked in front of a group of men than to wear a bikini, considered a symbol of oppression.”

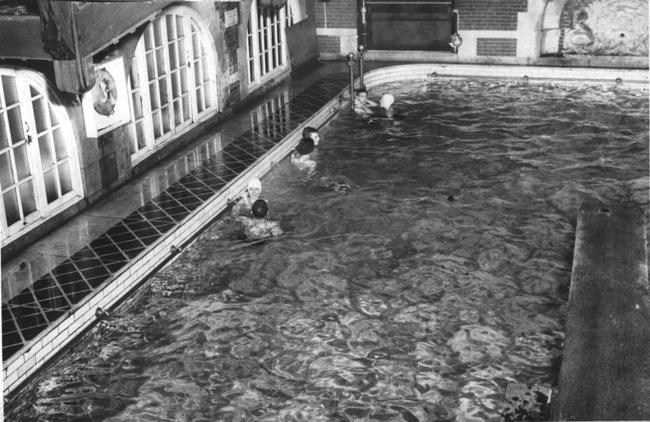

The pool, with rather demure bathers, presumably after 1971, but we’re not entirely sure.

The Adams House pool became a vivid symbol of coeducational living in Harvard’s Houses when the 1970 Harvard-Radcliffe yearbook published a photograph of nude swimmers in and around the pool. Spread across two pages, the photograph, which left little to the imagination, was captioned “The Harvard Experiment,” an allusion to The Harrad Experiment, Robert H. Rimmer’s racy 1966 novel of the sexual adventures of students in coed dorms. The notorious photograph preceded a section of pages that discussed how the arrival of women in the River Houses (and men in the Quad) had changed life at Harvard. The image may have aroused much interest among the members of the freshmen class, because Adams House became extremely popular in subsequent years.

Adamsians attempted to remain discrete about their naked antics and adopted a “what happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas” attitude when several newspapers and magazines took an excessive interest in the pool. Nevertheless, word spread of nude swimming in the pool. In replying to an invitation to a March 1971 event at Harvard, author Kurt Vonnegut promised to bring a “rented dinner jacket” and, if allowed, a female companion. He also requested a change of venue: “I understand that there is now mixed nude bathing in the swimming pool of Adams House. Could the meeting be adjourned to Adams House later on?”

Some Adamsians swam laps in the pool and found the exercise a welcome break from an evening of studying. Others frolicked on the diving board and tossed a ball around. More vigorous students participated in coed nude water polo games, which were intense enough to inflict at least one broken nose. Water polo was too adventurous for some women. One of Fran Schumer’s friends later told her, “I’m surprised grown-ups let us behave like that.” Not all students used the pool. Murray Dewart ’70 recalls, “I didn’t swim in the pool much. It was too filthy” – commenting purely on the water quality

The Harvard-Radcliffe Christian Fellowship

conducted baptisms there in the early 1970s.

They put a “Pool Reserved: Baptism” sign on the door to let Adamsians know

the pool was not available for swimming.

The pool also was used for more sacred and sedate purposes. The Harvard-Radcliffe Christian Fellowship conducted baptisms there in the early 1970s. The Christian Fellowship opted for the Adams pool because the Charles was too cold and the Indoor Athletic Building (now the Malkin Athletic Center) too public. They put a “Pool Reserved: Baptism” sign on the door to let Adamsians know the pool was not available for swimming.

In hindsight, the 1970s seem the golden age of the Adams House pool. Students swam frequently during the afternoon and evening lifeguard hours and illicit late-night use seems to have been rare, although not nonexistent. The pool’s mechanical systems functioned well, ensuring that it rarely, if ever, needed to be closed for repairs.

Over the years, the mandatory-swimsuit hours were occasionally adjusted to accommodate more modest swimmers. Sometimes hours were reserved for women only. In the spring of 1972, a new policy requiring swimsuits at all hours was suddenly and mysteriously imposed, perhaps in response to alumni or parental pressure. After a referendum of House residents, the former policy was quickly restored, although swimsuit hours were expanded to include 7:00–9:00 p.m., as well as 3:00–5:00 p.m. A decade later, there was a minor uproar when the head lifeguard, who also happened to be a leading campus conservative, attempted to expand swimsuit hours. Regardless of whether the change was politically motivated, Adamsians protested. Grace Ross ’83 declared: “We don’t wanna wear suits…We want to skinny dip.” The swimsuit-optional hours were restored and the practice of coed nude swimming continued until the pool closed, although nudity was never required.

Performing in the Pool

Adams House alumni may recall many late-night “performances” in the pool, but the pool also hosted at least four theatrical and musical events before it was officially transformed into a theatre.

“It is an indisputably Shakespearean

circus, the Bard doing the breast-stroke,

the actors barnstorming with the kind

of relish rarely unleashed in Harvard

theatre,” cooed the Crimson.

In 1978, Peter Sellars ’80, directed what was probably the first and definitely the most famous play in the pool. He staged Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra in and around Westmorly’s waters, taking full advantage of the atmospheric spaces of Adams House. Cleopatra lounged on a barge at one end of the tank, while Antony called to her from the diving board. The actors periodically splashed the audience and led them to “Rome” (A-entry). Those who attended remember the excitement of being immersed in a circus-like event. The reviewer for the Crimson wrote that “it is an indisputably Shakespearean circus, the Bard doing the breast-stroke, the actors barnstorming with the kind of relish rarely unleashed in Harvard theatre.” By all accounts, Topher Dow ‘81 was a flamboyant highlight as a particularly sensual Enobarbus. Jenny Cornuelle ‘81, Sellars’ égérie, starred as a breathtaking Cleopatra. The Crimson reviewer concluded that it might be worth watching the director and actors, because “you’ll hear from them again.” Sellars went on to direct numerous contemporary and classical operas and plays, winning wide acclaim for his innovative and provocative stagings.

Mark Prascak ’88 in his 1987 production of Peer(less) Gynt attempted to emulate the success of Sellars’ Antony and Cleopatra. Prascak trimmed Ibsen’s play to a manageable length and updated it with modern references. From time to time, actors jumped into the pool, which represented the ocean, and splashed around. The Crimson reviewer was baffled: “Does it work? Is it just an avant-garde joke? [Is it] worth seeing? I don’t know; it’s hard to tell.”

In 1989, the pool was the scene of a performance that is not as famous as the Sellars production of Antony and Cleopatra but was just as memorable to those in attendance. A group of Adams House students performed John Cage’s musical composition, “Inlets,” near the stairs and in front of a fireplace at one end of the pool. The piece consists largely of the amplified sounds of water flowing through conch shells. The audience sat around the edge of the dimly-lit pool and, as the spirit moved them, removed their clothes and dove or slid into the water. The pool filled with nude swimmers—many of whom had rarely or never used the pool before—as the concert progressed. Participants felt an other-worldly sense of serenity as the water and the music enveloped them.

The final musical performance in the pool—at least when it still had water in it—took place at the end of the 1989–90 academic year. As part of a series of year-end parties in B-entry and Adams more generally, the student rock band Imipolex G (named for a substance in Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow) played a concert in the pool. “Love Hurts” and other songs echoed through the pool and around Westmorly’s interior courtyard. A collection of amplifiers perched on the pool’s edge made swimming unwise.

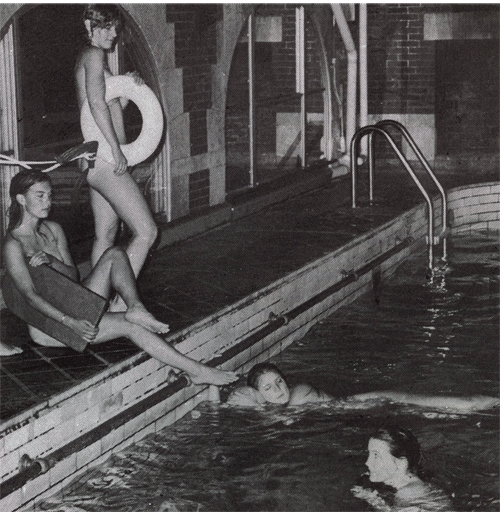

The pool, as seen in the 1984-85 Confi guide. Lovely ladies aside, the architecture is very much showing its age.

The Party to End

All Pool Parties

In its final years, the Adams House pool continued its most notable tradition. Relatively few students swam in the pool during the hours when a lifeguard was present, but some continued to take advantage of the swimsuits-optional policy. Unbeknownst to most undergraduates, resident tutors (who were fortunate enough to have their own keys to the pool), their guests, members of the Senior Common Room, and a few Harvard administrators and faculty swam nude at all hours.

Adamsians frequently swam in the pool after hours. Helpful tutors would lend their keys to students. Ingenious undergraduates found ways to break in. “The thing about the pool is that it’s an invitation to decadence,” said Mitchell Orenstein ’89. Tales abound of large groups of undergraduates skinny-dipping after House events such as the Mardi Gras party or private parties. Some alumni even claim that swimming was not the only social activity in the pool…

Although it was still the scene of much youthful exuberance, by the mid-1980s the pool was showing its age. It had to be closed for extended periods for repairs. The water was often an unhealthy shade of green. The ancient filter finally failed, spewing rust into the pool and requiring that the pool be drained for months. The filter was eventually replaced, but the accumulating problems of the pool were ominous portents of things to come.

The “Bungle in the Jungle” party invited

guests to don “jungle attire …

a.k.a. wear only what you need.

The invitation quoted the Book of Genesis

(2:25): “The man and the woman were

both naked, but they were not embarrassed.”

The event that heralded the beginning of the end for the pool was an infamous party on Saturday, March 17, 1990 – an event that remains as murky as the waters of the pool when the filter was malfunctioning. Sometime after midnight, a resident tutor opened the pool and let in several students. At about the same time, Adamsians flocked to a party in F-42. Hosted by sophomores Ulysses Chang ‘92, Thomas Lauderdale ‘92, and Fabian Birgfeld ‘92, the “Bungle in the Jungle” party invited guests to don “jungle attire … a.k.a. wear only what you need.” The invitation quoted the Book of Genesis (2:25): “The man and the woman were both naked, but they were not embarrassed.”

Perhaps it is not surprising that party guests eventually made their way to the pool.

At about 3:00 a.m., Adams House Senior Tutor Janet Viggiani found 75 to 100 people in and around the swimming pool. The lights were out and swimsuits were scarce. As Lauderdale recalls: “In walks the senior tutor—lots of naked people in the pool, at 3:00 a.m., with the lights off.” Viggiani was not concerned by the nudity and she did not think that the swimmers had been drinking too much, but she felt that “there were just way too many people for safety to be maintained.”

Contrary to popular belief, the pool was not permanently closed after the March 17, 1990, party, but undergraduate use was curtailed and the Adams House administration did its best to prevent late-night swimming. Although the pool was closed until April 8, it reopened briefly between then and the summer of 1990, when it became obvious that water was leaking from the pool. The water level fell alarmingly and mysteriously, raising the possibility that water from the pool was flowing into the foundations of Westmorly or creating a health hazard in the adjacent Adams House kitchen. The pool was thus closed in the summer of 1990. Between then and 1992, Harvard analyzed the pool’s problems, obtained estimates of the cost of repairs, and ultimately decided to drain the pool forever. Students protested the decision to close the pool, to no avail. Thomas Lauderdale ’92, then chair of the House Committee, deplored the demise of the pool: “Ooh, I was so bitter…” A classmate lamented, “A dry pool is a big loss. If you can’t let loose in college, when can you?”

Harvard administrators never confirmed that the pool’s swimsuit-optional policy and reputation for late-night parties contributed to the decision to close the pool, but it seems plausible that concerns about Harvard’s image and legal liability were taken into account. There is no doubt, however, that renovating and reopening the pool would have cost over $100,000 and the ancient plumbing might have required further repairs. Years later, Adams Co-Master Sean Palfrey summed up the ambiguous rationale for the decision to drain the pool: “The pool was closed because Harvard believed it was threatening the structural and moral foundations of the House.”

The Pool Theatre

The pool theatre readying for a performance of ‘The Exonerated” in 2009 with Julienne Coleman ’11 and Lindsey Ross ’11 ushering.

Photo courtesy Kris Kribbe

When it became clear that Harvard would not pay to repair and reopen the pool, Adams House Drama Tutor Art Shettle proposed that the pool be converted into a theatre. Master Robert Kiely and Adams House Superintendent Billy Long enthusiastically embraced the idea. Using the pool space as a theatre was absolutely consistent with the House’s long thespian tradition. Fred Jewett, dean of Harvard College, provided the funds for the renovation and conversion of the former pool.

During 1992–93, the pool was transformed into a theater. The renovation retained and restored many of the original features of the pool. The space retains much of the character of the Westmorly Tank. Adamsians who remember the pool still see the river god’s familiar face behind the stage area. The beamed ceiling remains, although it has been shored up with additional wooden braces, and the skylights, a salient feature of the space, roofed over. The marble around the pool has regained its luster. Artifacts of the swimming-pool era, such as a list of rules for swimmers, remain prominently displayed. Apart from the absence of water, the biggest changes were the removal of the shower and the installation of theatre-style seats.

The pool theatre opened on Halloween weekend, 1993. Master Kiely said “I’m enormously pleased with it” and predicted that it would be a “huge boon” to Adams House. The first production was La Cage aux Folles, which seemed highly appropriate in light of the House’s support for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered students and its annual celebration of Drag Night. Directed by David McMahon ’94, the musical was, according to the Crimson, “engaging and entertaining” in “true Adamsian style.” The reviewer had “no doubt that the Adams House pool has finally found its true calling.” Since then over 100 shows, as well as concerts, films, and other events, have been staged in the pool theatre. Productions have ranged from Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus to the traditional Adams House Farces.

Eduardo Perez ’12 and Steven Maheshwary ’12 perform in “The Exonerated”

Photo courtesy Kris Kribbe

The pool theatre has been improved since the initial renovation. New lighting and an updated sound board have been added in recent years. According to current Adams House Drama Tutor Aubry Threlkeld, it is “by far the most popular venue for undergraduate drama in the Houses.” The pool theatre now has been in existence for almost as long as the era of (official) coed nude swimming in the pool.

Reflections on the Pool

The Adams pool was always a place where the usual rules and social conventions could be cast aside, a setting for uninhibited performances, creative, and unforgettable experiences. Does the same spirit pervade the pool theatre and make it an ideal stage for innovative and creative drama? Perhaps it does. But a lot of Adams House alumni will always miss the pool.

Some alumni periodically wonder if the pool could be reopened. Given the popularity of the pool theatre and the high cost of renovating the swimming pool, it seems certain that swimmers will never again splash through Westmorly. Even if the pool were to be restored and refilled with water and swimmers, it would not recapture its past glories. Today’s Adams House students are not the students of the 1970s and 1980s. If nothing else, behavior in the pool might be very different in an age when everyone carries a cell phone with a camera.

The pool that lives on in the memories of Adamsians probably surpasses the pool that actually existed. The parties were wilder, the swimmers more beautiful, and the water cleaner and warmer. The pool’s closing helped to elevated it to mythic status. Just as the break-up of the Beatles made them even more iconic, the closing of the pool has made it even more legendary.

Nevertheless, the actual pool was extraordinary, even if its luster and allure may have been inflated by an excess of nostalgia. As one alumna from the late 1970s and early 1980s described it, the pool had a “fabulous uniqueness” that students appreciated then—and now. Where else could one find a similar combination of spectacular architecture, spirited behavior, and memorable performances? For many, the pool was the heart and soul of Adams House. It fully deserves the cherished place it occupies in the memories of Adamsians.

Sean M. Lynn-Jones, contributing editor of the Gold Coaster, was one of the last people to swim in the Adams House pool.