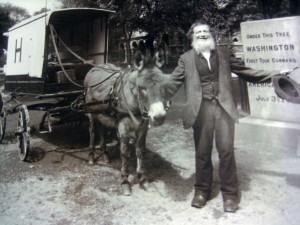

John the Orangeman, Harvard's Mascot, as he appeared in FDR's day. This is the picture we have in the Suite. If you look carefully in the lower left-hand corner (this image, as all the others in the piece, can be expanded by double clicking the picture) you will see another source of John's financial success: by 1900 or so, he had moved into selling copyrighted souvenir photos.

Without fail, whenever I give a tour of the FDR Suite, someone asks me who’s that bearded man with dancing eyes, merrily peering out from the frame on the mantle piece. There’s something about the sparkle of his expression that simply captivates visitors. My inevitable reply: “That’s John the Orangeman, Harvard’s mascot. He sold fruit to the students at a time when citrus was a rarity, and become hugely popular with the undergraduates. He and his cart, pulled by a donkey named Radcliffe, were a feature of the College for over five decades.”

A thorough answer, but not a very satisfactory one. Who was this man, really, and how did he become so popular with the students? I decided to do a bit of digging in the Harvard Archives to try and find out.

Well, let me tell you: In the spirit of the soon to be demised News of the World, there seems to be more to this story than first meets the eye!

To begin with, it’s important for you to understand that John was not just popular, he was hugely popular. The archives have more than six folders of Orangeman pictures dating back to the 1870s, many of them official photos, and a whole other file of clippings, memorabilia – even two short published biographies written by former students. Here’s one of my favorite photos from the Archives collection, showing a parade passing through Harvard Square. (The view is looking east down Mass Ave. The low building right of middle is where Holyoke Center now stands. The tall building at center is extant and holds Leavitt and Peirce.)

This is a truly spectacular photo for many reasons. For one, the level of historical detail is amazing; notice, for example, the maze of telegraph and telephone wires almost clouding the sky. We forget that not everything in the "good old days" was quite so pretty. The picture is not captioned or dated, but judging from the bunting, the summer dress of the paraders, and the two top-hatted men marching behind the wagon each with a "9" on the front, I would guess this to be the late 1890s. (Again, click to expand; see reader's comment below for exact dating.) Courtesy, this and following photos: Harvard University Archives.

At first glance, this picture doesn’t seem to have much bearing on our story. But look again at the lower right side: just passing out of view, there are John and Radcliffe, cart and all, being hauled down the street on some sort of large wagon, the Victorian equivalent of a parade float.

So, famous indeed. Here’s the official bio:

Born John Lovett in Kenmere, County Kerry, into a farming family about 1833, John left Ireland during the famine, first for Boston, then later to Cambridge, where he took odd work. Then one day, finding himself with nothing to do, he went to “over an the Carmon to wartch the byes play barl.” (The transliteration of the brogue is from one of his student biographers.) Seeing that the players were thirsty after the game, he offered to fetch them a jug of water from his nearby flat (laced with “lemon” and “molasses”, as he put it) for which the students were quite graceful, requesting another. He complied, and the students, wishing to thank him, passed around a hat, collecting about two dollars, along with a suggestion that bringing fruit to their rooms later might prompt similar reward. Thus, a career was born. John began selling various small items to the students, mostly bananas and oranges. Each day he made his way into Boston to buy at the wharves. By mid-morning, basket in hand, he would be in the college yard, “depending on stray customers between the recitations and lectures; in the afternoon, if the weather was warm, he visited the ball fields; while in the evening he made his tours through the dormitories.” So grateful were the students that Class of 1881 gave him a handcart: “They warnted to give me a darnkey too but I be afraid the Farculty mek a row about havin’ ‘im in the Yard.” At first an overzealous Yard Manager prohibited the cart from entering, but petitioned by the students, the Faculty allowed finally allow John and his cart admittance – the only person ever permitted, before or since, to sell goods in the Yard. As age advanced, so did rheumatism, and seeing John in distress, the class of 1891 bought him a donkey and cart. In winter, Radcliffe the donkey pulled a small sleigh. Soon John, with or without Radcliffe, was not only selling goods but making the round of the various football games, brought by the team to locations as far away as New York, where he cheered tirelessly for his school. (On state occasions like the Harvard-Yale game, Radcliffe was decked out with special crimson bloomers.) Fame and increasing fortune brought John a wife, plus a three-story two-family in Cambridge, which amazed student visitors with its size and comforts, given his humble occupation. Stories about John abound, but an oft-quoted one was this:

One day a visitor accosted John in front of Hastings Hall, and wishing to draw him into conversation, pointed to the College seal on the iron gate and asked him what Veritas meant. John bowed respectfully and replied: “I’m not sure fr’ind, but I guess it means ‘to hell with Yale.’”

John Lovett died in 1906 at the ripe old age of 81.

That’s the official story… Neat, pat and tidy.

But why was he so popular? There were a host of other notable characters at FDR’s Harvard, but none quite so beloved. What was John’s secret? His biographers often cite to his jovial personality:

“You all know him, Old John, who is the first to welcome the Freshmen in the autumn, and the last to shake hands with the Seniors on Commencement and perhaps drink him God-speed from a flowing bowl of punch. He well remembers the time your father was in College; will tell you where he roomed, how he lived, who his friends were; perhaps he will even whisper in your ear of a narrow escape he had, in the early part of his Freshman years, from being asked to resign. Is there one who has not tasted and orange or banana from the little white handcart?”

Also to his integrity: “For those who know him well he is rather an interesting study, though his brogue is a trifle hard to comprehend at times. One of the best traits of his character is that he can never be induced to speak ill of anyone. Mingling as he does with the men of various sets and cliques, he necessarily hears more or less slander, but if asked his opinion about a man, his only comment is ‘Aw, he’s a good fellah, frind.'”

And on and on…

But then I came across one very curious sentence: “Who has not been comforted, when sorely pressed by creditors, by John’s ready willingness to trust him for any amount?”

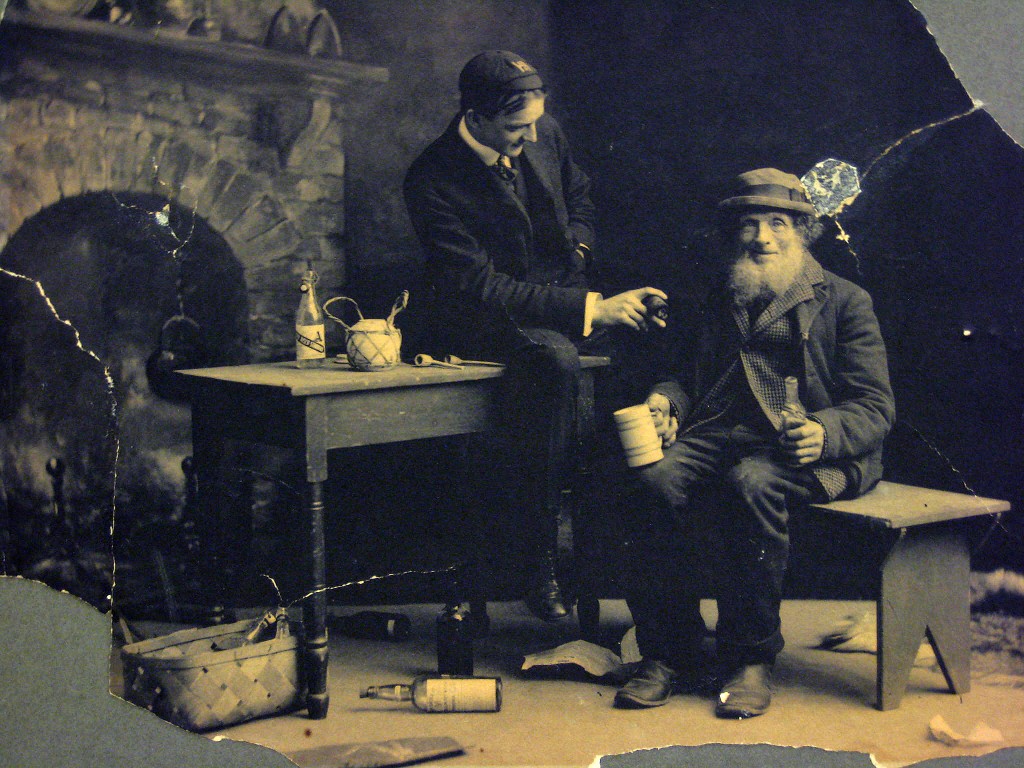

Ah ha… The plot thickens. Perhaps it was more than just a juicy orange that gave John his appeal. Still, a bit of money-lending on the side couldn’t account for such lasting hail-and-well-met. I was about to give up, thwarted by the silence of the past, when just before the closing hour, I came across this picture stuck to the back of one of the folders. Unlike other pictures of John, many of which were “official” shots reproduced again and again, this was distinctly different, and one I had never seen before:

Again, there is no caption, other than to note that the photo came as part of the estate of a member of the class of ’01. The scene’s obviously been professionally staged in some photographer’s studio, for reasons now forgotten – perhaps as a private memento (or perhaps, even more rare, as a publicity photo for Brown of Harvard, which premiered in Boston in 1906, and in which John played a bit roll as himself, just a few months before his death.) But however clouded the origins of the picture, its subject is certainly straight-forward enough, and meant to evoke a familiar scene – at least for those in the know: a grinning student, having polished off the bottle on the table, holding a cigar large enough to choke a horse, looks gratefully at a still imbibing John the Orangeman, empty liquor bottles littering the floor and more poking from of his basket – the very one supposedly full of fruit!

Hail and well met, indeed!

So if I remind you, dear reader, that Cambridge was dry in those years, and that the only alcohol to be had was by going to Boston, does not the reason for John’s immense and continued popularity across five decades of thirsty students suddenly become crystal clear?

I’m thinking John bought more than oranges on those daily trips to the wharves, and sold more than fruit on his nightly rounds.

20-years gone but not the least forgotten: the Class of 1881 chose to feature John on its 20th Reunion Medal. Acquired just last week, the medal will hang on John's picture in the Suite.

And remember that admiring bit about John never betraying a confidence? Neither it seems, did his “byes.” In fact, the whole thing is one long inside-joke, known by all, and advertised by none, across 50 classes of Harvard men – the don’t-ask-don’t-tell of its age. If it hadn’t been for this one surviving photo, John’s open secret might be a secret still.

Of course, I can’t prove any of this.

But it fits, doesn’t it?

Can’t you just feel it?

It’s important to note that this potential revelation doesn’t at all reflect badly on John. (He wasn’t selling booze to minors. There was no drinking age in those days, and the only law he was skirting was the selling of liquor in the town of Cambridge.) Nor does this diminish in any way the genuine regard generations for Harvard men had for this beloved character. On the contrary. In the end what we get is the image of a cunning Irish Robin Hood fighting to outwit the dastardly Sherwellian forces of the Cambridge establishment for the benefit of the (not so) poor inhabitants, and I’ll admit, if true, this vision brings me a quiet satisfaction. Often the view of our Harvard past becomes too perfect, too polished, too mannered. The memories are all noble, the deeds all gallant, the people, upright & upstanding. This little bit of Irish roguery, abetted and encouraged by grateful generations of scheming undergraduates, is just the kind of thing to add a welcome bit of humanity to the tale.

So, here’s raising a glass to you, John.

Some People Read History. Others Make It.

Come make a little history: support the FDR Suite Foundation!