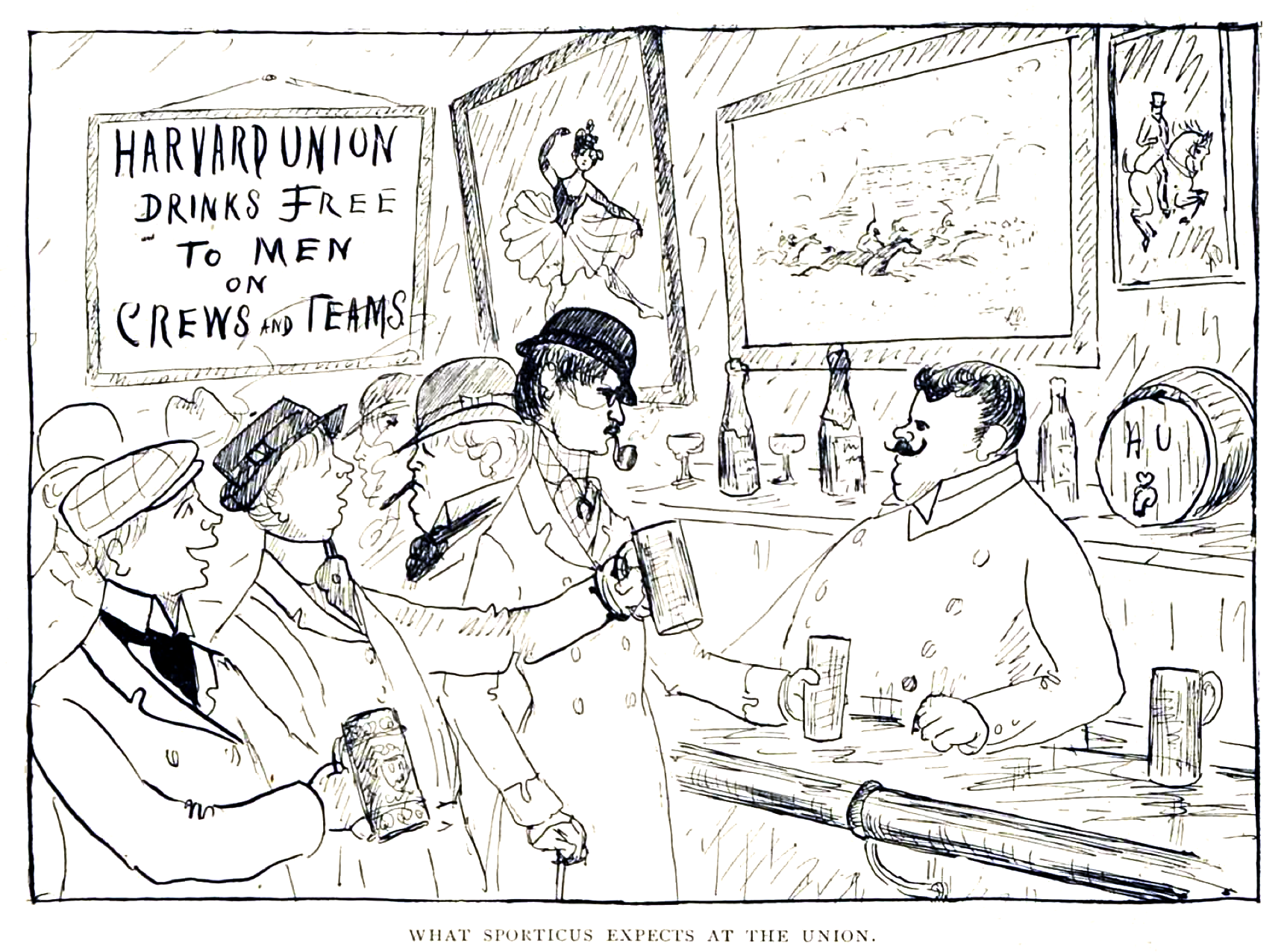

Not to give our neighbors in the castle too much credit, but there is some interesting history to be learned from period pages of the Harvard Lampoon, especially when it comes to determining the mores of FDR’s Harvard. Take the image below, for example, one that is particularly relevant for today as it mirrors a problem soon to be faced by the new Smith Center that the University is building in Holyoke Center. The Harvard Union was the first attempt to establish a place where alumni and students could co-mingle, and it was a hugely expensive flop, for the very reason depicted below: it, like all of Cambridge, was dry. The only liquor available was at private clubs, which is one of the main reasons that final clubs were (and are) popular today: they served booze.

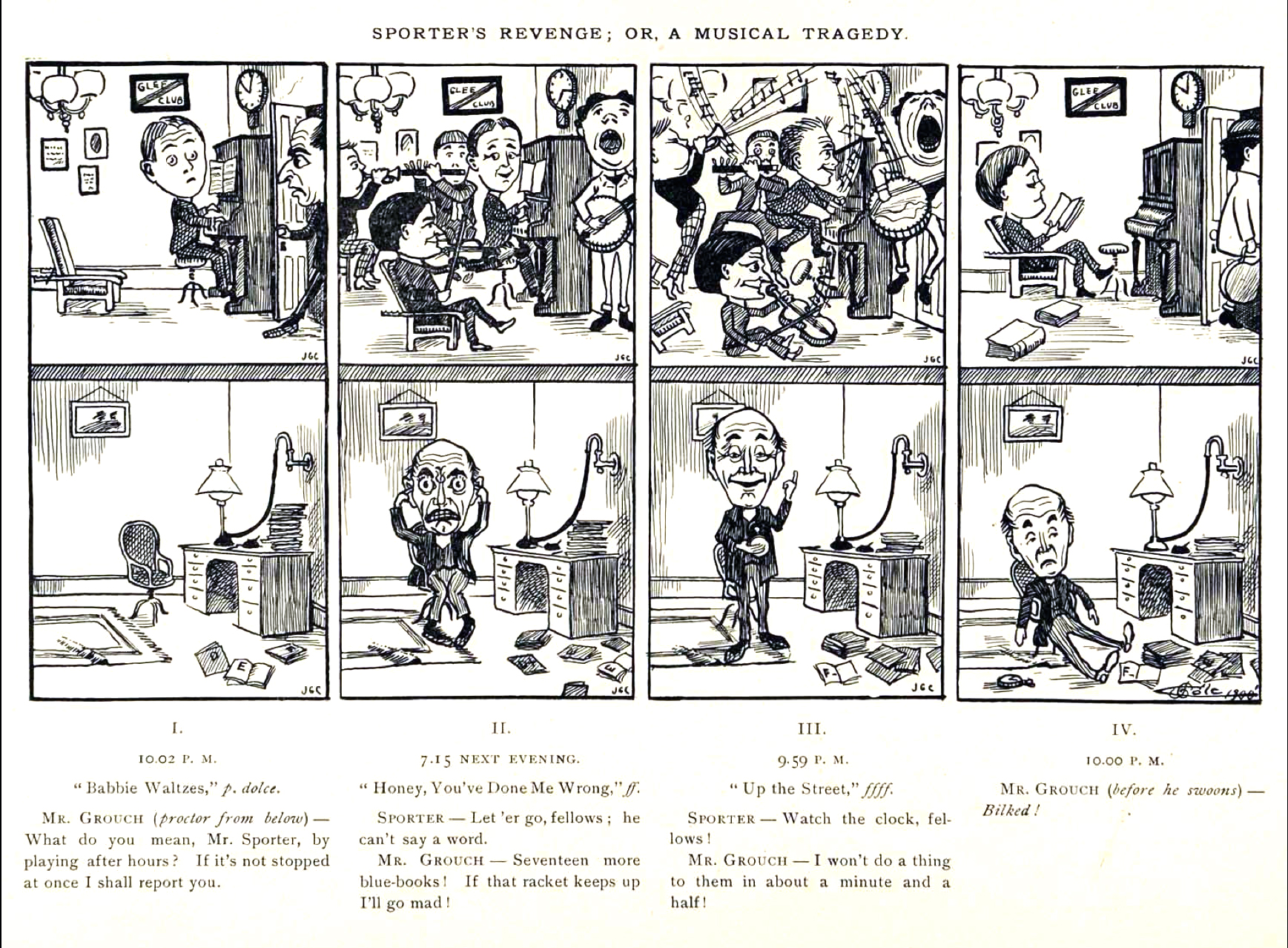

The next image took me a while to figure out. The key is that the proctor from the floor below is the same character entering the door of the piano-playing student in the first panel. He’s playing, piano dolce, “Babbie Waltzes.” (Hear the tune HERE on a wax-cylinder recording.) Also note the time. Apparently 10PM was the cut-off for loud noise in individual suites, so to take revenge on the proctor for reprimanding him him the night before, the next day “Sporter” arranges for a little concert with his friends. The music starts with “Honey, Don’t Get Me Wrong” a forgotten ragtime tune of the day, and ends with “Up the Street,” a march still played by the University Band. What caught my eye was the gas lamp on the proctor’s desk. These lamps were attached by rubber “extension tubes” to either a wall or ceiling gas outlet. Frankly, it’s amazing that the whole place didn’t burn down — or explode — many times over. While electricity was available in certain deluxe suites like FDR’s, electrical outlets wouldn’t be invented for several more years.

What’s interesting about the next panel is not the joke —it’s a play on grub (food) and grub (caterpillar) — but rather something that is almost forgotten today. Those lines above the Square aren’t meant to indicate clouds, they are telegraph, telephone and electrical lines. In 1900, competing companies ran their own wire to each client, so a single large building might have hundreds of wires running to it from all directions. This tangle persisted until the 1930s, when individual concerns were absorbed into larger entities and regulation of utilities became the norm.

What’s interesting about the next panel is not the joke —it’s a play on grub (food) and grub (caterpillar) — but rather something that is almost forgotten today. Those lines above the Square aren’t meant to indicate clouds, they are telegraph, telephone and electrical lines. In 1900, competing companies ran their own wire to each client, so a single large building might have hundreds of wires running to it from all directions. This tangle persisted until the 1930s, when individual concerns were absorbed into larger entities and regulation of utilities became the norm.

Here’s a photographic view, looking the other way, that better reveals this crazy-maze of wires. That’s John the Orangeman on the cart, btw, heading for a Harvard rally. (If you don’t know about John, by all means click the previous link as he is critical to the FDR Suite story.)

Here’s a photographic view, looking the other way, that better reveals this crazy-maze of wires. That’s John the Orangeman on the cart, btw, heading for a Harvard rally. (If you don’t know about John, by all means click the previous link as he is critical to the FDR Suite story.)

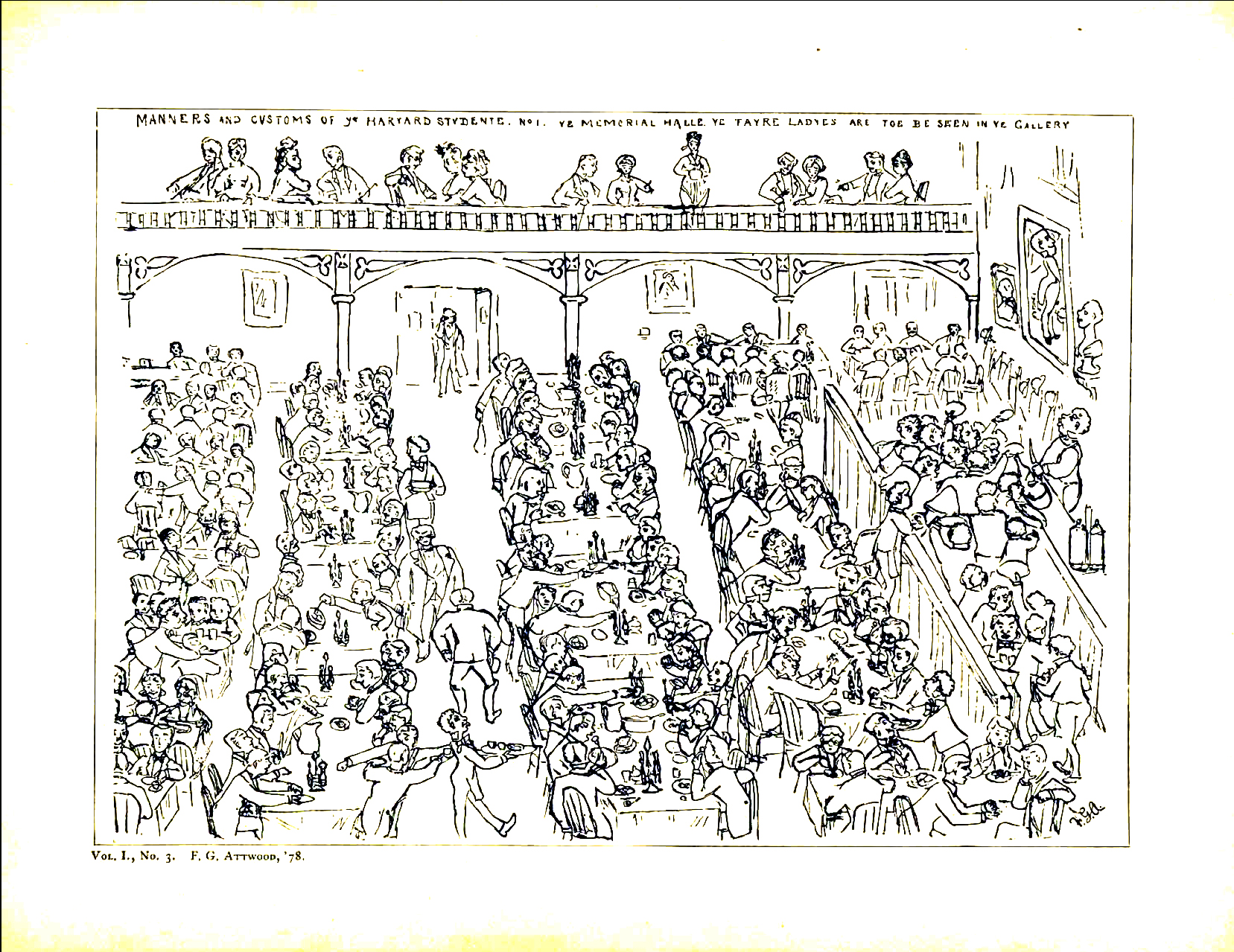

The panel below explains the grub joke: it shows the interior of Memorial Hall, where most of the undergraduates ate. Notice the gawking guests in the balcony, which was open to the public and used as a viewing gallery by the locals — a perfect spot for a chaperoned young lady to get an overview of prospective suitors to invite to her next “at home” day.

This last is one of my favorites, not just because of the great drawing style of S. A. Weldon, a classmate of FDR’s, but rather as it shows just how luxurious life in the Gold Coast actually was. No smelly gas lamps here. There is an electric desk lamp (which had to be plugged into the overhead fixture each time it was turned on, which meant gas or kerosene was still the norm) as well an assortment of comfortable furniture, walls and shelves chock-a-block with personal mementos, even velvet portieres on the door. And of course our boy under the desk has just come up from a dip in Claverly’s “tank,” the first of what would be a succession of ever larger private swimming baths on the Gold Coast. Considering how little we knew about this period in Harvard’s history when we started, it’s always reassuring when pictures like this come along that show many of the very same objects in the FDR Suite today — a gratifying indication that our representation of Gilded Age life at Harvard is reasonably on track.

This last is one of my favorites, not just because of the great drawing style of S. A. Weldon, a classmate of FDR’s, but rather as it shows just how luxurious life in the Gold Coast actually was. No smelly gas lamps here. There is an electric desk lamp (which had to be plugged into the overhead fixture each time it was turned on, which meant gas or kerosene was still the norm) as well an assortment of comfortable furniture, walls and shelves chock-a-block with personal mementos, even velvet portieres on the door. And of course our boy under the desk has just come up from a dip in Claverly’s “tank,” the first of what would be a succession of ever larger private swimming baths on the Gold Coast. Considering how little we knew about this period in Harvard’s history when we started, it’s always reassuring when pictures like this come along that show many of the very same objects in the FDR Suite today — a gratifying indication that our representation of Gilded Age life at Harvard is reasonably on track.

Like what you’ve been reading? Support us by donating to the Foundation. It’s quick, safe and easy.

There is still one missing piece to this whole Porcellian-Fly Club biz, which Rick Porteus has promised to check on. Originally, there were only two “final” clubs, the A.D and the Porc, so called because they were the terminal points of the club system. You could only join one. All the others were “waiting” clubs, the Edwardian equivalent of circling the airport, waiting to land. One by one, however, these waiting clubs voted themselves final during this period. Precisely when this occurred at the Fly is still being researched. The only reason this matters is that it rewrites the narrative in a rather potent way: instead of some variant of the oft-used phrase “FDR was forced to settle for the less prestigious Fly,” which occurs in almost every FDR bio, the tale should possibly read “FDR chose the Fly with his Groton chum and roommate Lathrop Brown, but was foiled in his attempt to advance to the Porcellian.” Or, “FDR failed to get into the Porcellian and at the urging of his roommate Lathrop Brown, decided to join the Fly.”

There is still one missing piece to this whole Porcellian-Fly Club biz, which Rick Porteus has promised to check on. Originally, there were only two “final” clubs, the A.D and the Porc, so called because they were the terminal points of the club system. You could only join one. All the others were “waiting” clubs, the Edwardian equivalent of circling the airport, waiting to land. One by one, however, these waiting clubs voted themselves final during this period. Precisely when this occurred at the Fly is still being researched. The only reason this matters is that it rewrites the narrative in a rather potent way: instead of some variant of the oft-used phrase “FDR was forced to settle for the less prestigious Fly,” which occurs in almost every FDR bio, the tale should possibly read “FDR chose the Fly with his Groton chum and roommate Lathrop Brown, but was foiled in his attempt to advance to the Porcellian.” Or, “FDR failed to get into the Porcellian and at the urging of his roommate Lathrop Brown, decided to join the Fly.”