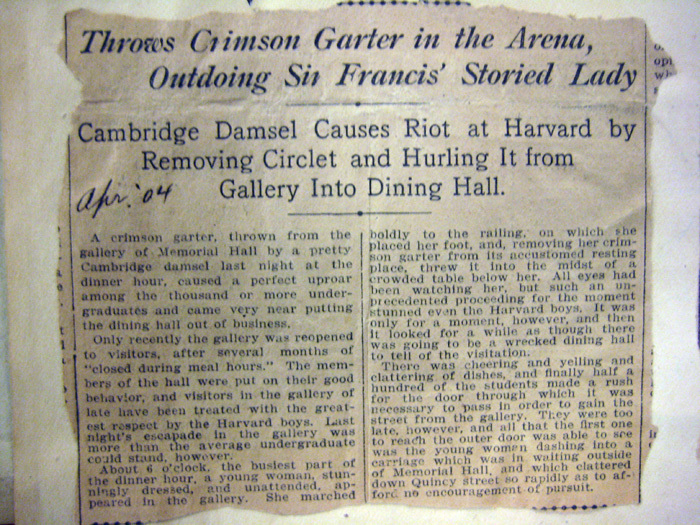

“To whom the conception of a Harvard Union is due is beyond my knowledge; but we owe the fostering of the idea to many men, and we owe the grounds to the Corporation. As you see, it is the result of Harvard team-work, of mutual reliance, the future abiding place of comradeship; and therefore let it never and in no place bear any name except that of John Harvard. We will nail open the doors of our house, and will write over them: –’The Harvard Union welcomes to its home all Harvard men.‘” The conclusion of the dedicatory speech given by Henry Lee Higginson October 15, 1901 and attended by FDR.

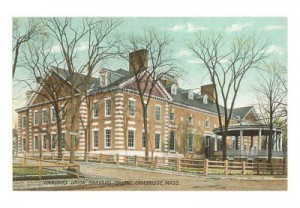

The Harvard Union, from a period postcard. Note that the breakfast room on the far right was originally open to the air. The Crimson Offices are on the far left, on Quincy Street

In my day (that’s to say the mid 80s) when one mentioned the Union, the immediate impression was of a rather run-down dining hall where Freshmen trudged three times a day for meals. Well, perhaps “rundown” is a bit of an exaggeration, but certainly “dowdy” seems fair –not to mention a bit strange. I remember sitting there the fall of my first year, admiring the grandiose decor: the baronial stone fireplaces on either end, one now stuck incongruously behind the salad bar; the ornate wood paneling; even the immense antlered chandeliers – given by TR someone said – and reportedly the last of over 30 moose heads and other trophies that once graced the room. (Truth be told, my appreciation of the fixtures was dimmed somewhat by the pads of butter that were routinely lobbed into the antlers by smart-aleck jocks, just waiting to melt on unwary diners.) Later, wandering around the many nooks and cranny’s of the basement and upper floors, I discovered a warren of rooms, most of which were locked and obviously unused. The whole place had a melancholy, lost-in-time ambience, sad in a way I could never quite understand.

Henry Lee Higginson, painted by Sargent. This portrait still hangs in what is now called the Barker Center.

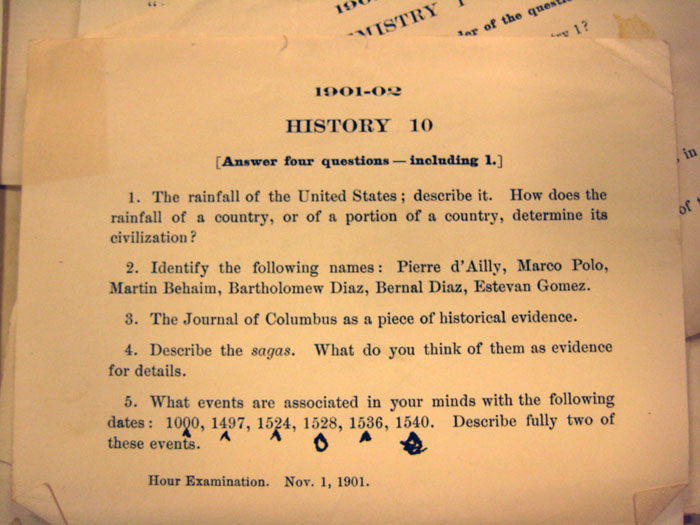

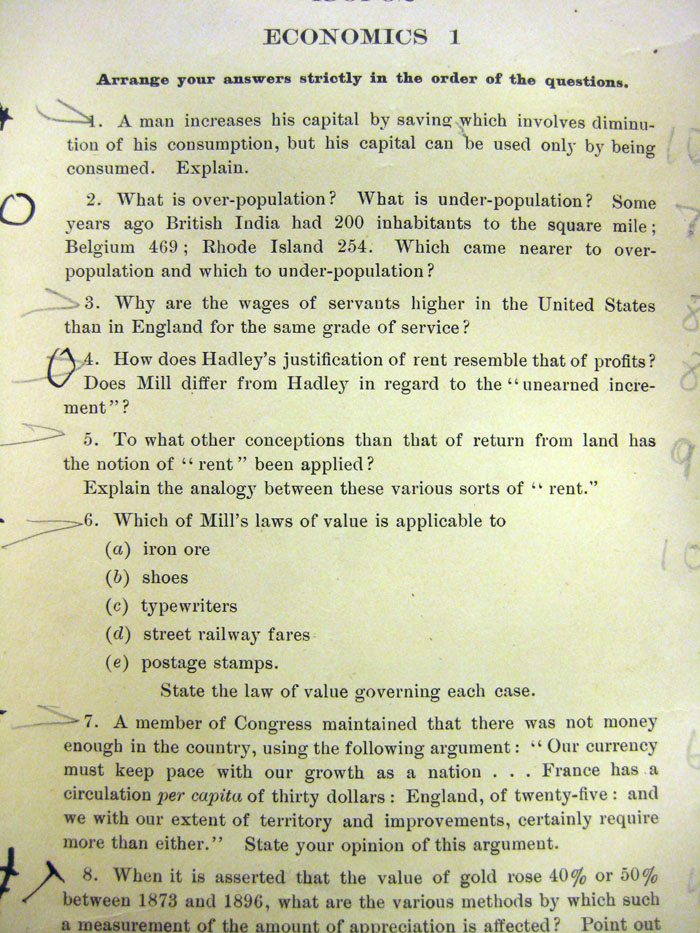

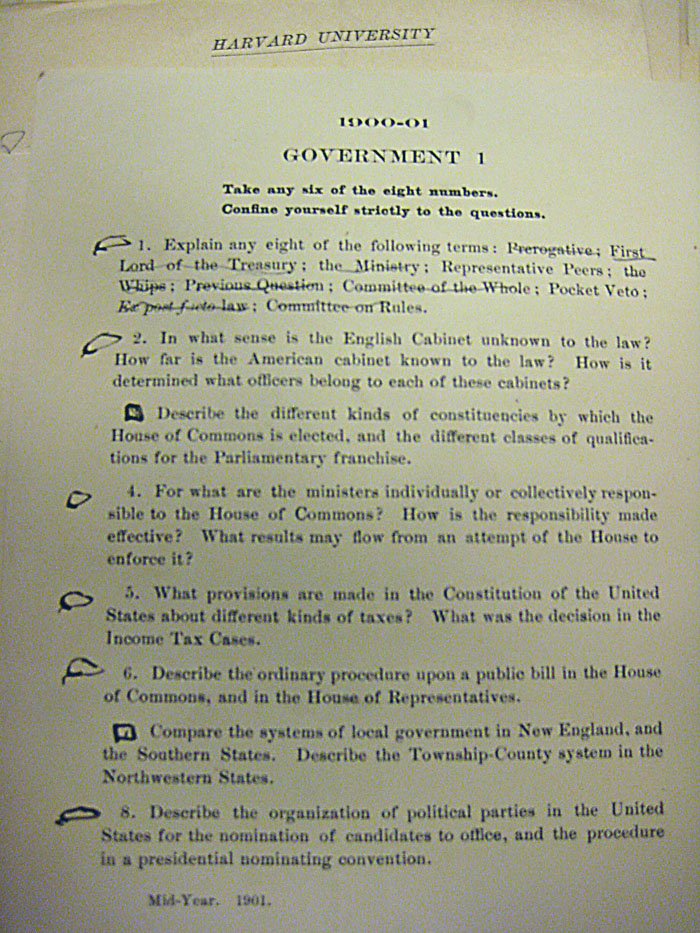

It certainly didn’t start out that way: the 1902 Union, designed by the illustrious firm of McKim, Mead and White with a $150,000 gift from Major Henry Lee Higginson, was erected as a shining example of social reform through architecture. Conceived as a gathering place for students unable to afford the luxuries of the final clubs, the Union was intended to be literally just that – a unifying force where “pride of wealth, pride of poverty, and pride of class would find no place.” Its very location was, in fact, a symbolic compromise: constructed on the former site of the Warren House, which was moved next door, the building sits precisely equidistant from the wealthy digs of the Gold Coast and what was, at the time, the poverty of Harvard Yard. Membership was open to all, without the elaborate initiation rituals of the clubs, and annual dues were kept deliberately kept low – from $10 for current students, to $50 for lifetime privileges for alumni, all in order to encourage active use. The building, a triumph of Georgian Revival design, was equipped with an amazing array of features: a massive Great Hall (then used as a club room, but later the Freshman dining hall); a full restaurant (open to ladies on weekends – they had their own special dining room other times); a lunch counter for a quick bite; an athlete’s training table; a barber shop; cigar and news stands; billiard rooms (where students could obtain free instruction “from a well known professional”; a library with 6,000 volumes; meeting rooms and other social spaces; as well a guest rooms for visitors. It was in fact, a final club for the masses. The only thing the Union lacked was the ability to provide its general membership with that favorite collegiate brew, beer. Cambridge was officially dry at the time, and to be served “exhilarating beverages” one needed to belong to either a private final club, or cross the Charles into Boston. FDR attended the Union’s “impressive” opening ceremonies in October of 1901 – without, of course, surrendering his memberships in other, more exclusive, not to mention more liquid, clubs. Later that year, he joined the Union Library committee, writing Sara to tell her he had spent $25 of the check she had sent to buy the library “a complete set of St. Amand’s work, and also a Rousseau, both of which we needed.”

The TR chandelier, now in the Barker Center

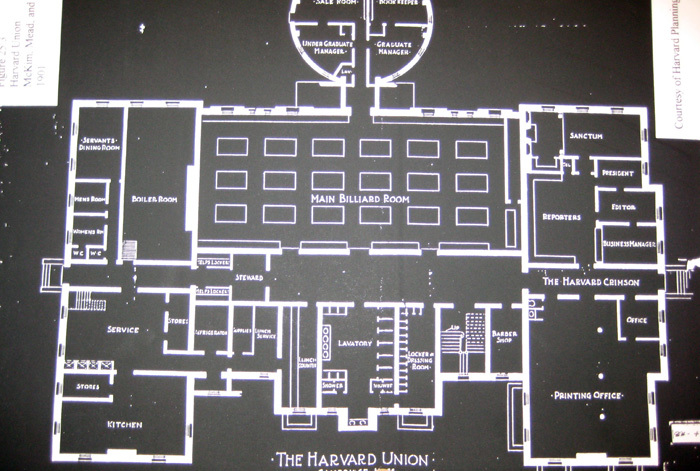

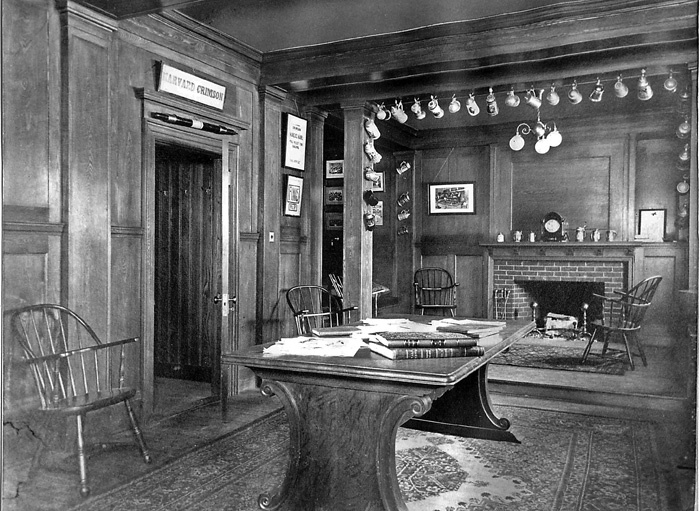

Most importantly in the Rooseveltian context, however, the brand new Union was the brand new home of the Harvard Crimson. McKim had taken pains to design a custom space for the College newspaper, after officials had convinced a reluctant Crimson management to occupy a suite of offices in the basement of the new building. (The Harvard Monthly and the Advocate had already agreed to move in upstairs.) Previously, the Crimson had rented a dingy series of private rooms on Massachusetts Avenue that had become obviously inadequate, and the paper had been considering a new site for some time. When the College’s offer arrived however, it wasn’t greeted with the enthusiasm one might have expected. According to published accounts, the Crimson management feared that accepting space from the University might mean surrendering editorial integrity. Reading between the lines, however, it also seems that, given the dry nature of the building, the Crimson staff feared that the College might seek to limit the historically bibulous aspect of publishing the College daily. Clearly however, an arrangement suitable to both parties must have been concluded, because the final plans detail a special series of rooms for the paper, including an ornately fireplaced Sanctum replete with beer steins. The Crimson moved in as soon as the building was completed, and it was here FDR had his office when he became President of the Crimson in 1903.

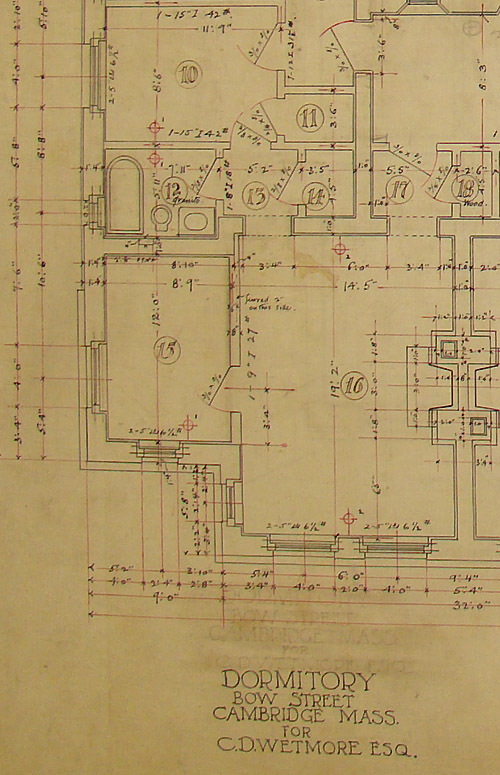

The following views, with the exception of the plan and FDR’s own pictures from Hyde Park, come from The Harvard Crimson, 1873-1906

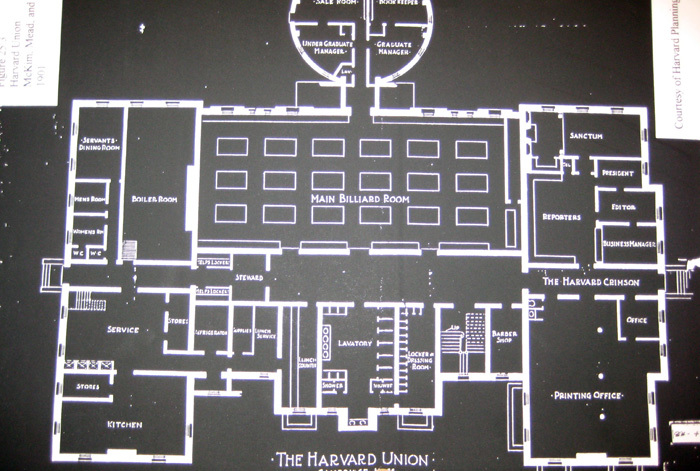

- The is the McKim plan for the basement of the Union, showing the Crimson offices on the right.

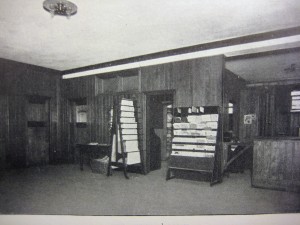

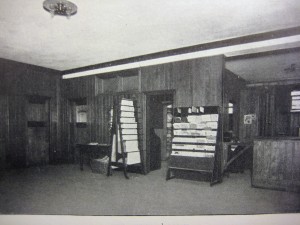

- The reporter’s room

- The composing room

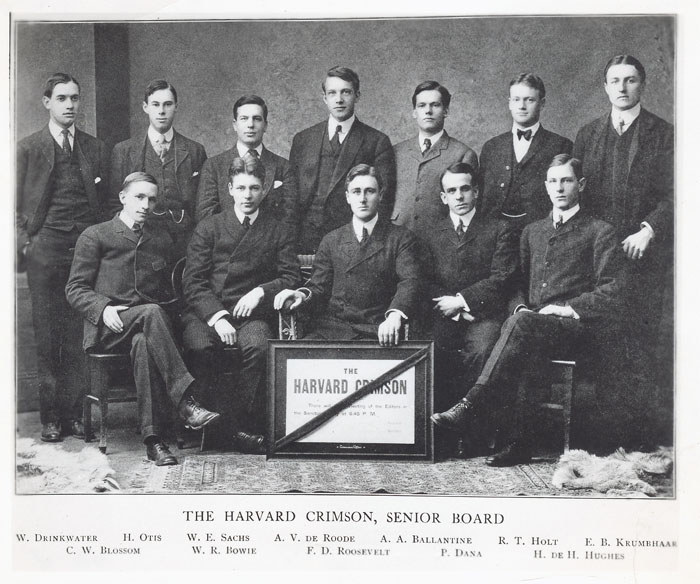

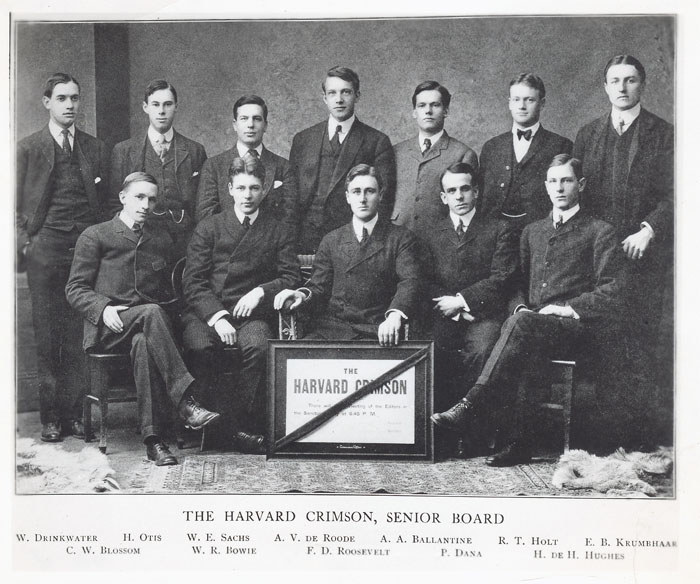

- FDR as Crimson President with the other officers.

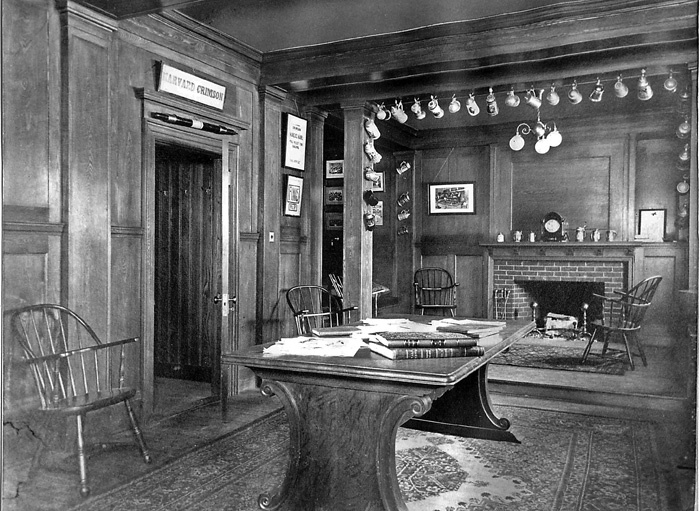

The officers' offices: the door to the left of the table was FDR's; the editor, next to the right; and the counter was for the business manager.

The Sanctum, looking west. This was FDR's own picture, which still hangs today in Hyde Park. Note the beer steins, and the piano at the far left: obviously not all was about reporting! Courtesy the National Park Service, and the FDR Presidential Library and Museum

Another picture from Hyde Park. The Sanctum, looking east. Courtesy the National Park Service, and the FDR Presidential Library and Museum

This unmarked entrance was the door to FDR's Crimson offices on Quincy Street.

After FDR left Harvard, the Union continued on, though as years passed, it became clear it would never fulfill its initial promise. (Click here to read about the early high hopes for the Union in a 1902 article from the New York Times). As the administration discovered to its dismay, many of the men at Harvard in the early 20th century didn’t particularly desire social equality, and despite a heady start, Union membership began a steady decline after 1908, putting the organization on a shaky financial basis almost immediately. A movement to make Union membership mandatory, and term-bill the annual expense, never succeeded. The Crimson decamped for its current quarters on Plympton Street in 1915, and by the late 1920’s the facility was largely vacant. Higginson’s noble experiment had failed. When the House system was organized in 1930 (itself an even grander attempt at integrating the student body) the Union became the freshman dining hall, its original purpose almost – but not quite – forgotten. It seems the University had contemplated the relative merits of continuing to use Memorial Hall as a dining facility – as it had been since its inception – or adapting the old Union for the freshmen. In making the decision, College officials “had looked carefully into Major Higginson’s will,” to quote a 1957 Crimson article, and “discovered that the benefactor had made allowances for failure of his institution as a club, and promptly decided to name its new freshman dining hall the Harvard Freshman Union.” Shades of Mrs. Widener and “touch not one brick!” Ultimately however, either the penalties contained in the will expired, or else the University simply decided to accept the loss and move on, as the Union was finally closed and controversially remodeled in the late 90’s. The building is now the Barker Center for the Humanities, and the rooms where FDR inked articles and cried for copy, a series of bland office spaces.

Edward Penfield

Edward Penfield