One of the most interesting things about the FDR Restoration Project is that I never know down which fascinating historical path I’ll be drawn next. Take yesterday for instance: Dave Robinson, grandson of Chester Robinson ’04 arrived in Cambridge from Maine bearing a whole host of original materials he and his family are sharing with the Restoration. It’s a real treasure trove, and one that I’ll be detailing over numerous posts during the next year. But of immediate note was a volume he showed me that I hadn’t ever seen before: the Harvard Yearbook of 1904.

“Ah ha! What’s this?” I cried, eagerly clasping the thick volume. “Nothing less than a complete catalog of the state of the College in FDR’s last year, with pictures! Ho! HO!”

Dave kindly consented to a loan, and later that evening I came across the following notice:

THE NEW PLAN OF CLASS DAY AFTERNOON EXERCISES

(Now, this could be interesting, I thought; after all FDR was on the Class Day committee, his first elected office in fact… What do we have here?)

“When in 1897 the College authorities first objected to the Tree Exercises, there was raised in the undergraduates’ mind a problem, which, it is hoped, has been finally settled this year. In 1897 the undergraduates, finding themselves in danger of losing a custom descended to succeeding classes from time almost immemorial, promised to lessen the fight around the tree by lowering the height of the flowers from the ground. They were allowed to hold the exercise in this modified form, which however achieved only a moderate success. These modifications proved so distasteful to the next class, that after considerable discussion, they decided to give up the old exercises, and start somewhat different ones around the John Harvard statue in the Delta. As the fighting for flowers had become objectionable to many, it was omitted, or rather, left in such a modified form as to be almost unrecognizable; and instead cheering and singing were introduced. In this form the exercises have been held for six years, but they have never been considered highly entertaining, or altogether successful. In addition, the feeling has gradually grown that the wooden grand stands erected for the occasion were dangerous on account of fire, but as there seemed to be no substitute which would obviate this difficulty, nothing was done about it. This year, however, after the class of ’79 had given the magnificent stadium to the University, this naturally suggested itself as a suitable place to hold the troublesome exercises… and to give a more substantial tone to the whole… by moving the Ivy Oration from the morning…

___

OK. Sounds reasonable. But tree exercises? What ever do they mean, “tree exercises”? And what’s this mention of fighting? And which tree? On Class Day? Whatever for?

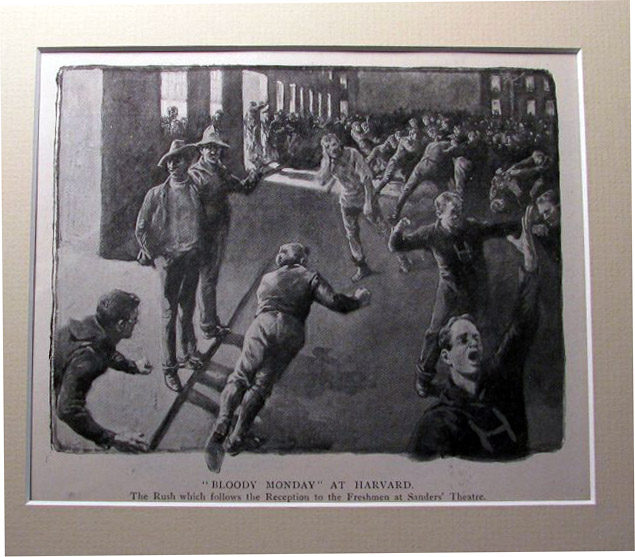

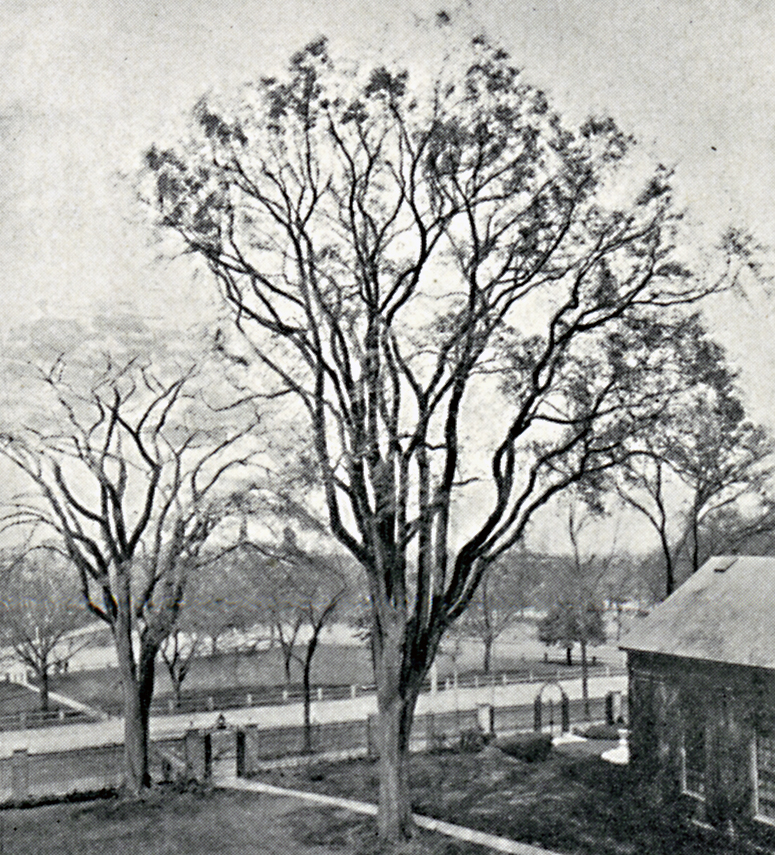

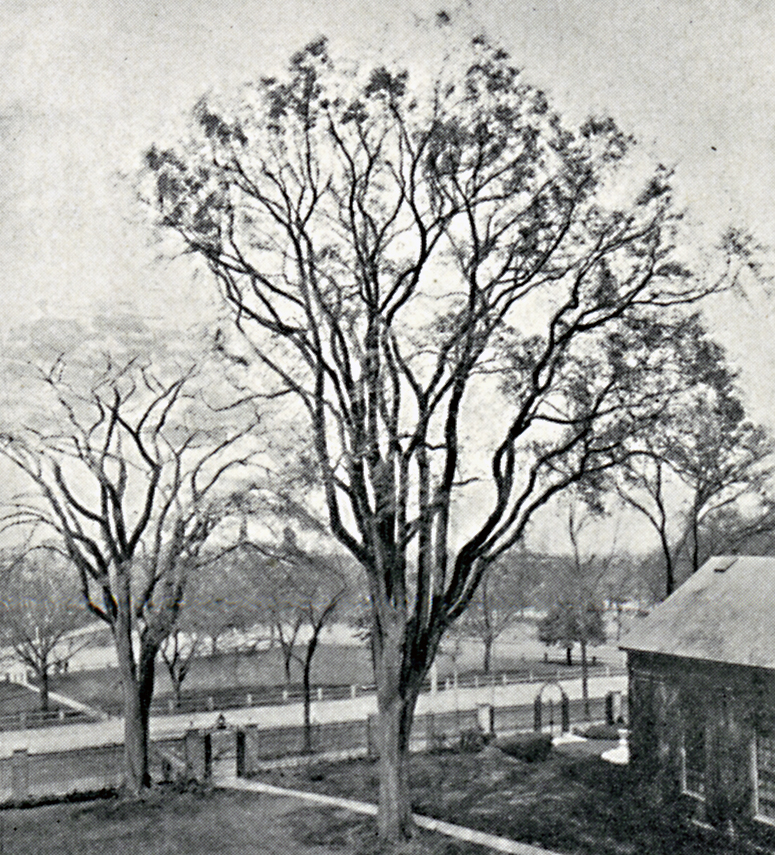

Then, leafing (pardon the pun) through the volume, I discovered a small picture:

So, that’s one piece of the puzzle solved: there’s the tree, and that’s clearly Holden Chapel, with the Cambridge Common visible beyond, before iron fencing and Lionel Hall closed off this side of the yard. But still no explanation of what these strange exercises were about.

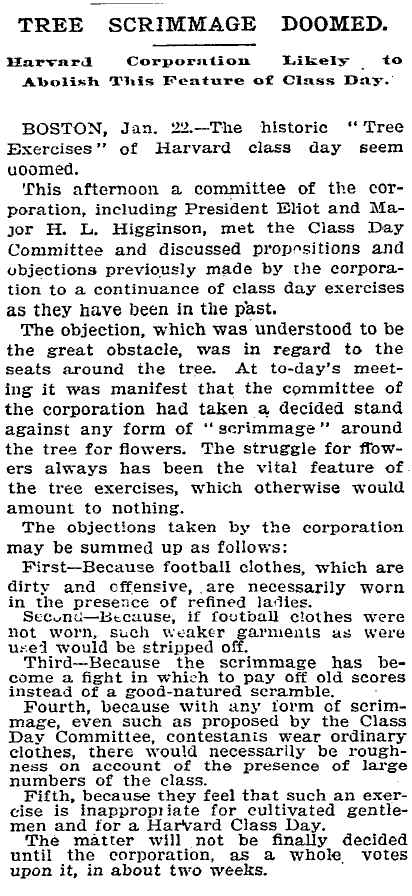

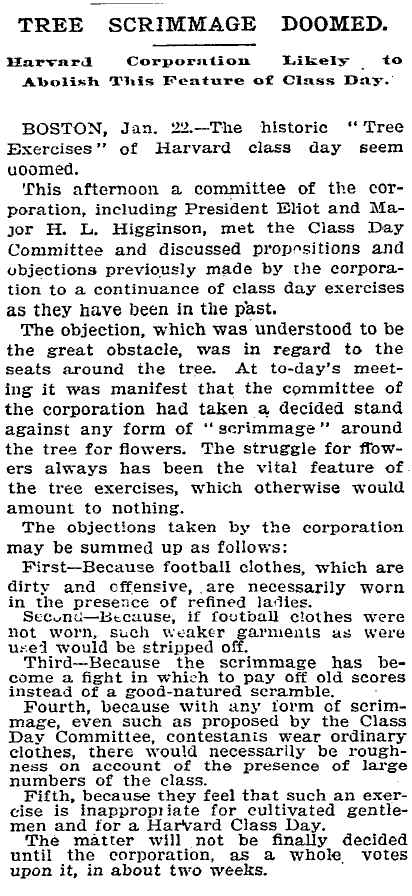

Continuing backward down the historical path, I next found this, from an 1897 article in the New York Times:

Holy smokes, the Corporation’s now involved, ladies are being insulted, Harvard men are wearing “dirty football gear” to Class Day, and the news is considered important enough to have made the Times! You’ve got to be kidding. What exactly could be the nature of this “struggle for flowers”?!! Now I really was intrigued, but while I discovered a fair number of references to the mysterious ceremony, I could find no explanation of why a group of grown men would wrestle each other for flowers tied to a tree…

Further into the past…

Then finally, from the 1880 Harvard Register, a suitably flowery article chronicling yet another President’s graduation ceremony, this time Theodore Roosevelt.

Around the old Class Elm, in the square formed by Holden Chapel, Hollis and Harvard Halls, and the fence on Harvard Square, tiers of seats in circus style were built. Shortly after five o’clock all of the thousand seats were occupied, chiefly by ladies, dressed in light and beautiful costumes, giving the whole the appearance of a gay parterre. Then enter at the gate between Hollis and Holden the juniors (1881) who seat themselves on the ground within the circle. Next come the sophomores (1882) followed by the freshman (1883). After these have taken their places, a group of graduates, many from the recent classes, file in, and seat themselves on the ground, facing the juniors.

Suddenly the rustling of the fans, the low hum of conversation is no longer heard. The music of the band and the cheering of the buildings announce by increased loudness that the seniors are approaching. As they enter, not in their full-dress suits as regulations of Class Day require, but in the oldest clothes they own, the juniors, sophomores, freshmen and graduates rise, and, in turn, greet them with a hearty “Rah! Rah! Rah!” each class attempting to excel in volume of tone and perfection of time. Then ’80 returns the compliment to ’81, ’82, ’83 and the graduates; and then cheer, with their utmost zeal and power, almost every object of college affection, beginning with “President Eliot” and closing with “the ladies.” When the class have exhausted their voices, they sing, as well as can be expected under the circumstances, the Class Song… The song over, hands are joined, each class forming a living chain, of which every link is resolved not to prove the weakest part. Now the word is given: round and round they go, the whirl grows furious, maddening. Fond parents looking from their seats tremble for the safety of sons who may chance to fall and be trampled by that writhing, seething mass, and sigh with relief when they see the rings broken, and attention drawn to the seniors alone, as they, at a given signal from the marshal, strive to grasp a blossom from the bouquets forming the wreathes which at a height of ten feet encircle the dear old tree. Pushed up against the tree beyond hope of release, those who were foremost served as stepping stones for the others. Up struggled an adventurous youth upon the heaving shoulders: he grasped at the tantalizing blossoms, and some of them came away with his touch, but he left the cuticle of his knuckles behind. Nor did he make off with his prize; for he took a plunge backward among those beneath him, lost his grasp upon his trophy, and it was borne away to deck the dress of some one other than she for whom he intended it. Another and another followed his example, some to meet with his fate, others to be more fortunate. More eager grew the struggle as the girdle was broken and torn away. The last flower is gone: there is nothing more to be striven for; and so, the most pleasant and unique rite of Class Day over, the seniors pass out to prepare for the softer and perhaps more entrancing pleasures of the evening.

There it was, at last. So simple, yet so unpredicted. And what an interesting sea change in attitudes between Teddy’s and FDR’s terms at Harvard! Only one question still troubled me: what was the origin of this bizarre custom? The 1904 Yearbook mentioned that the practice dated from “almost time immemorial,” but how long had this been going on?

Next, a hint in Thayer’s Historical Sketch of Harvard University (1890):

“Among the famous ‘rebellions’ I have already mentioned that of 1768, when, says Governor Hutchinson, “the scholars met in body under and about a great tree, to which they have given the name of the ‘Tree of Liberty’.’ Some years after, this tree was either blown or cut down, and the name was given to the present Liberty Tree, which stand between Holden Chapel and Harvard Hall, and is now hung with flowers for the seniors to scramble for on Class Day.

Ho! Ho! So now we are really stepping back… Our 1904 “Class Tree” was originally “The Liberty Tree,” a meeting place during “rebellions.” Political Rebellions? It was just before the Revolution War, after all. But no. Turns out that wasn’t it at all: Here’s Brian Deming, from his Student Discontent at Harvard Before the Revolution:

Called the Turkish Tyranny, as students likened Harvard authorities to Turkish despots, the 1768 student revolt came about “after the college changed its rules about how students could respond when asked in class to recite. The rule had been that students could simply say “nolo,” meaning “I don’t want to” and be excused. Under the new policy, which applied to all students except the seniors, students couldn’t excuse themselves so easily. Students had to get permission from tutors before class to be excused from reciting. As a consequence many students promptly asked tutors to be excused. Some tutors, such as Thomas “Horsehead” Danforth, turned down all requests. He subsequently had manure smeared on his door. Another tutor, Joseph Willard, had his room ransacked, and several had their chamber windows broken. Then rumors circulated that Willard his efforts to find the identities of the students who ransacked his room, had locked up a freshman “without Victuals, Fire or Drink.” A mob of students soon appeared at Willard’s quarters and broke the windows.”

In the following days, many students met to plan protests at a large elm tree, which they called their Liberty Tree, the same name given to an elm in Boston where Sons of Liberty gathered to protest the Stamp Act… Seniors, who had been aloof from the whole controversy, finally became involved and asked the faculty to properly look into recent events.When the faculty ignored the request, the seniors went to the College president to request a transfer to Yale.”

The entire senior class moved to Yale! Now that would have been something! Fortunately for Harvard (or for Yale), calmer heads soon prevailed, and when the freshman who had supposedly been imprisoned admitted that he hadn’t been restrained in any way, this particular revolt collapsed, but not before the custom of meeting beneath the Liberty Elm in times of crisis, or eventually, celebration, had been implanted in minds of future Harvard generations.

So here then, gentle reader, is the complete historical chain we’ve just followed backwards, in case you’ve forgotten or lost your way in all the twists and turns: In 1768, pre-Revolutionary student discontent at the cruelty of Harvard tutors leads to a rebellious series of gatherings which just happened to meet under a large elm which subsequently became immortalized as the symbol of Revolutionary activism which was commemorated each year by the placing of a wreath which subsequently morphed into series of wreathes and then a girdle of flowers, which one day, perhaps, a graduating senior attempted to carry off to his sweetheart, thereby inciting his fellow classmates to attempt rival feats of gallantry, which, due to the amusement and gaiety hereby invoked, initiated a friendly competition each June wherein the the most agile members of the class would vie for floral tokens much like medieval knights in a jousting match, a Class Day tradition which over the decades grew and became beloved by generations of Harvard men including Theodore Roosevelt until, as matters often do, things got out of hand and the Administration stepped in to prevent what it considered unnecessary rowdiness and uncouth behavior (not to mention, undoubtedly, undue risk of litigation), convincing the student body over threat of cancellation of this time-worn custom to adopt a series of modifications and changes which were neither liked nor well received, and which eventually resulted in such a diminution and devaluation of the practice that by FDR’s time, the Class Committee (of which FDR was a member) had no real objections to letting the Tree Exercises fall into abeyance, despite the heated protests of previous generations of alumni, who thoroughly missed the old ritual and predicted that this was just another symbol of the decadence and softness of present day youth, a chorus which was only finally stilled with the gradual disappearance of anyone who remembered what the Tree Exercises had ever been about in the first place.

Whew! Got that?

Regrettably for us, the Class Tree, too, is now long gone, carried off in the first great Elm blight that denuded the Yard just before the First World War. But perhaps, given such a grand history, it’s time to think about planting a replacement. There are several recently released Elm hybrids that are supposedly immune to Dutch Elm disease, and now that President Faust has declared that “Green is the New Crimson” a new Class Tree would seem an appropriately environmental gesture to link today’s classes with those hundreds past. And who knows, perhaps, if we’re lucky, on some warm June eve years hence, we might even catch glimpse of a grateful collegiate spirit or two, or three, once again singing, cheering and toasting our health beneath the graceful spread of arching branches.