(This is the second installment in a continuing series taken from the unpublished notes of filmmaker Pare Lorentz. For the introduction to these articles, click HERE.)

The Lathrop Brown Interviews: Part II – The Harvard Years

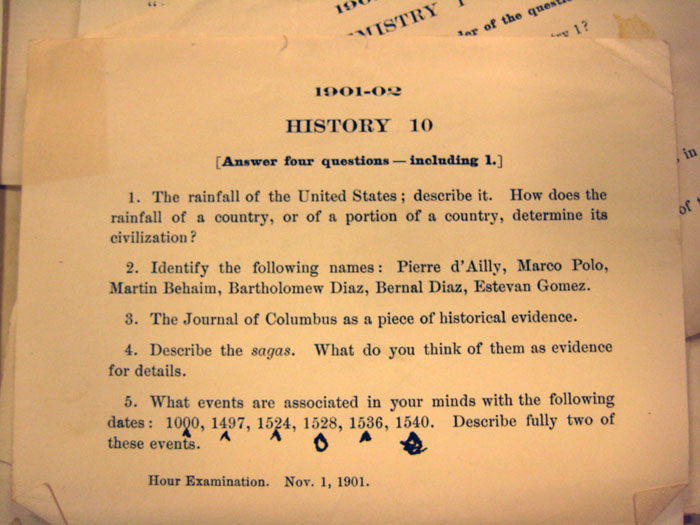

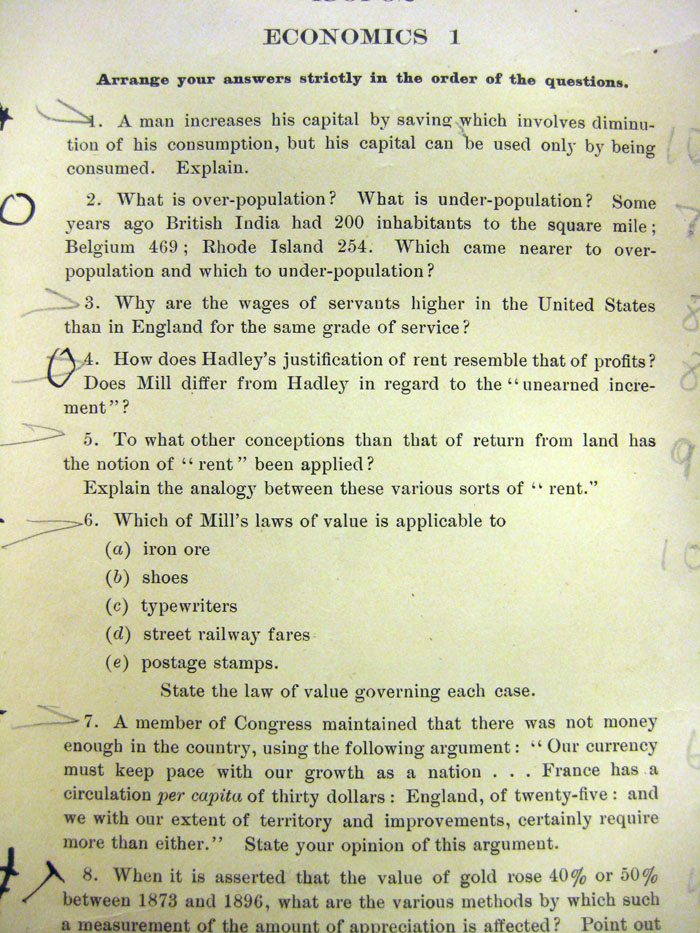

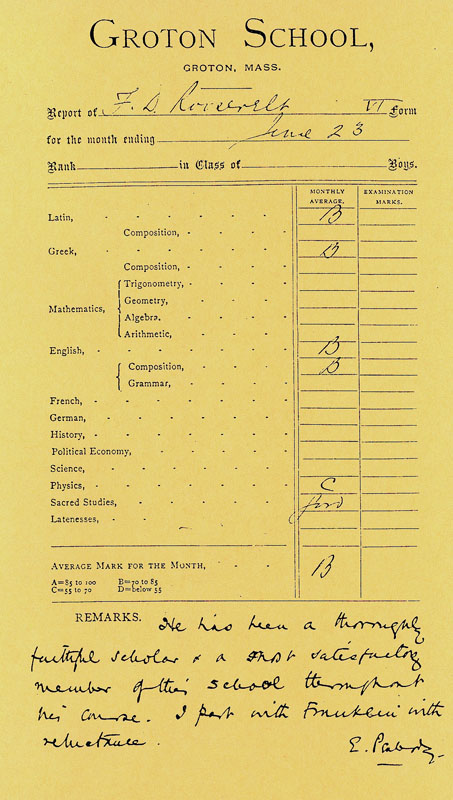

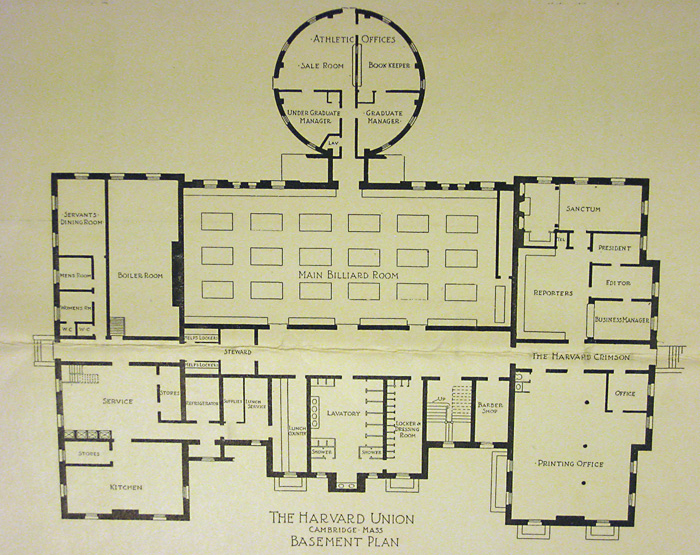

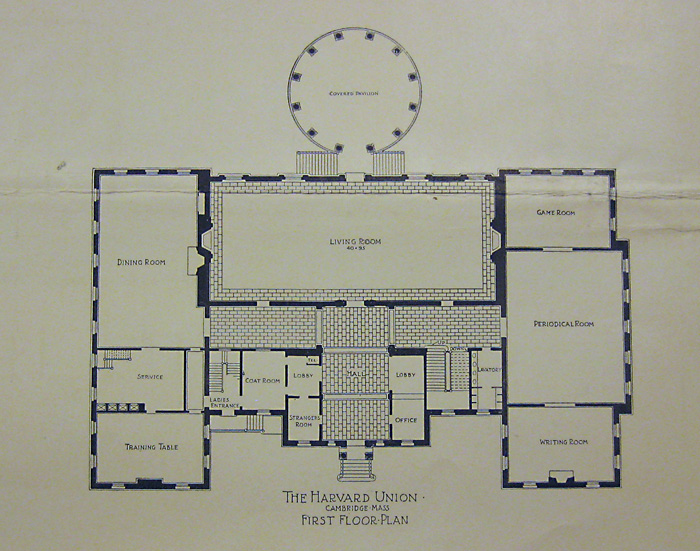

Having a good time was of major importance in those days at Harvard. Customary procedure was to study for ten days with a tutor before an examination and never open a book for the rest of the time. FDR and LB were both loyal to this tradition and quickly found activities to fill their time. FDR went to work on the Harvard Crimson, spending one year trying out, the next as an editor, and the third as editor-in-chief.

Many students carefully arranged their schedules so as to have no Saturday or afternoon classes. FDR was not as trivial about this as some of his classmates. He took the usual courses and achieved no scholastic honors, but he was extremely interested in his newspaper work and in the people he met. L.B. remembers that he was always agitating for something, but does not recall any specific matters.

FDR’s paramount interest was people, hence his liking for reporting. He met a great many more students and professors because of his work on the Crimson than he would have without it. LB cites an instance when he and FDR amused themselves one evening checking off their class list (about 600) to see who knew more of them. FDR won; he knew (had spoken with them, that is) perhaps half of the 600; LB isn’t sure but thinks this incident may have occurred late in their sophomore year.

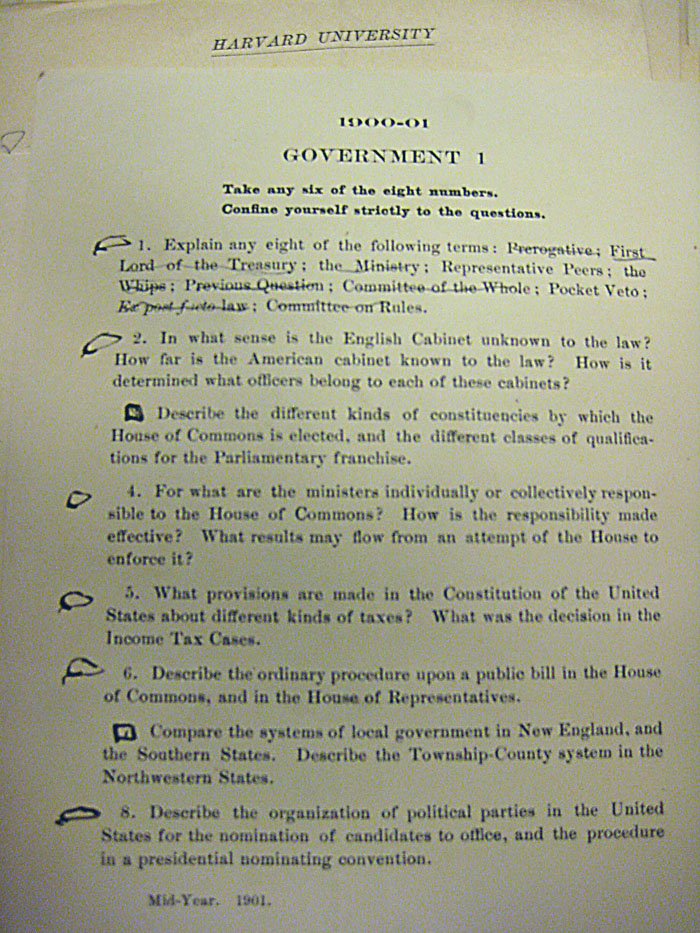

LB and FDR’s first Harvard Yale Game. Certainly the two were there, though the stadium wasn’t: it was still three years away. These tickets, incidentally, have convenient match strikers on the back: so much easier to light your pipe! Courtesy: Harvard University Archives

FDR came to Harvard as just another inconspicuous freshman. Once again, he was not outstanding in athletics. He continued rowing for exercise, but did not participate in interscholastic contests. He did not become a campus hero, but was well liked by all who knew him. He liked to go to parties every so often; he liked making noise and having a good time, but he was definitely not interested in dissipation. He would take a drink with his pals and get as much pleasure out of it as another would get out of a dozen drinks. He bubbled over easily.

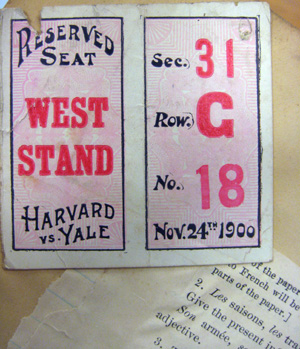

A gentleman’s dance card of the period. Courtesy: Harvard University Archives.

FDR enjoyed social activity. He dined out frequently with relatives and friends in Boston. Boston families, LB notes, were extremely hospitable toward Harvard students, especially if they had debutante or pre-deb daughters. FDR and LB were invited to the “Friday Evenings” – dances attended by the younger girls who had just put up their hair, lengthened their skirts, etc. The more sophisticated Harvard lads refused to attend, but FDR and LB, dutiful and proper, went regularly and enjoyed themselves…..

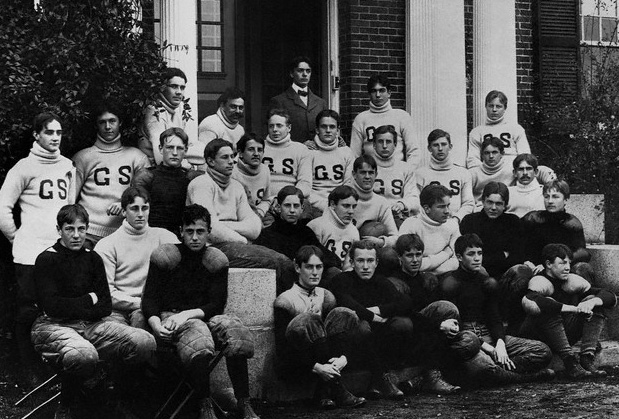

Harvard students who lived in Boston frequently invited out-of-town classmates, such as FDR and LB, to spend the weekends with them… FDR and LB roomed together throughout their Harvard years, but their interests were not always the same. FDR was concentrating on the Crimson, LB on football. [Editor’s note: LB managed the freshman team his first year, and the Varsity his last.]

LB notes that FDR was like a racehorse that makes a slow beginning and then comes up from behind. During senior year, it was the custom to elect several students for such prominent roles as First Marshal of the Class, Chairman of Class Day, etc. There were three marshals, and usually the captains of the baseball, football and rowing teams were elected. The chairmanship of Class Day usually went to some busy fellow who liked to run things. All four were invariably campus celebrities – “front runners” – who, after their brief spurt of glory, faded into oblivion.

FDR was elected to none of these posts. [He ran, and lost – his first taste of electoral defeat.] Instead he was chosen as class chairman, his job being to keep in touch with members of the class after graduation.

LB recalls a rip-roaring fight which FDR spark-plugged at the class reunion three years after graduation. It was customary for the class’s executive committee to be composed of graduates who lived in the Boston-New York-Philadelphia area and this committee had a tendency to become self-perpetuating, giving the rest of the class no opportunity to kick out those they didn’t like. LB feels fairly certain FDR was fighting from within; i.e. he was one of the committee anyway, but that he resented the injustice of the set-up. FDR started a big fight about it and managed to get everything changed.

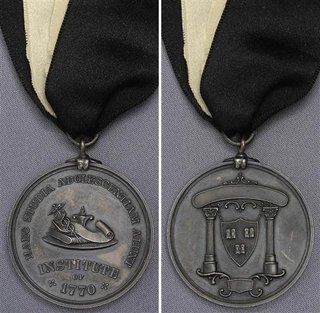

For years, we’ve wondered what the medals are that we so often see hanging from pictures in period Harvard student rooms like the one above. (Check out the picture at the far right) Thanks to LB’s comment about the Institute, and a bit of detective work, now we know….

FDR belonged to the usual number of clubs. He was a member of the Hasty Pudding, also of the Institute of 1770 (named after the year of its inception). The institute may have started with high purpose, as a literary society perhaps, but it wasn’t that in FDR’s and LB’s day.

In answer to the question about social consciousness: LB feels FDR definitely demonstrated this during his years at Harvard. It was plain enough, says L.B., that FDR’s attitude was not that of a reactionary Republican. Many a Harvard student, with similar background and upbringing spent his college years sitting in a club, looking out of the window and criticizing everyone who went by.

[The Porcellian, the most exclusive of Harvard’s final clubs, was famous for this, having installed a mirror that scanned the Mass Ave, obviating the need for members to present themselves at the window. FDR tried, and failed to be admitted. FDR had no inclination for this kind of activity. Instead of sitting around with his pals, he was out working for the Crimson, getting to know as many people as he could, talking with students and professors. He was constantly reaching out and broadening his interests.

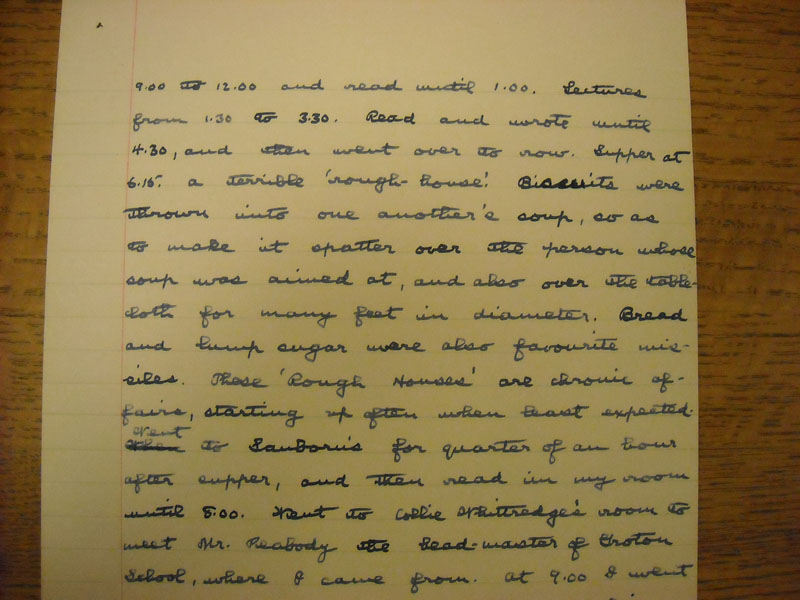

LB recalls FDR sang first bass in the Freshman Glee Club [LB sang second]. LB also recalls his and FDR’s initiation into ‘the Dickie,’ [The DKE, the next step after the Institute of 1770, and required of social climbers interested in joining a final club] which he described as a rough, beer-drinking organization. The freshman (chosen in “10’s”, to a maximum of 70 or 80) went through a week’s hazing, which called for their looking, and acting, like tramps. Unshaven, dirty, they had to do everybody’s errands. Everything had to be done on the run. No walking permitted. This week was a real test – no holds barred – and ended up with a wonderful party that called for a considerable amount of physical endurance. FDR had a fine time.

LB does not think FDR was particularly influenced by any of his professors at Harvard. As for his eligibility, LB says they never gave it a thought. Some of the Boston mothers may have, but not the lads and lassies themselves.

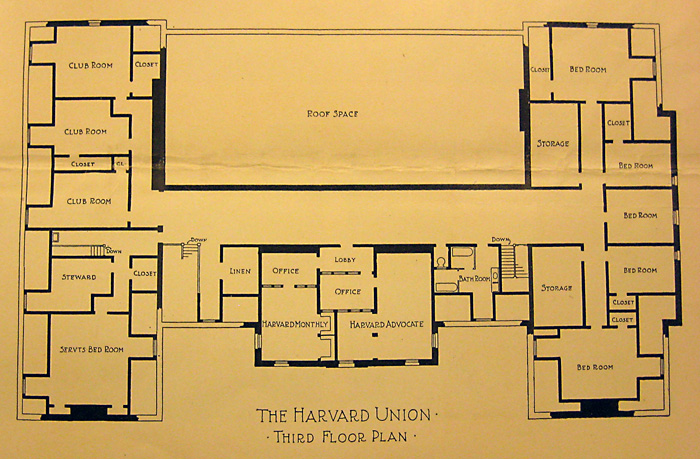

The top floor featured guest rooms for visitors (sans private bath, as was the custom of the day) plus the relatively modest homes of the Harvard Monthly and Harvard Advocate.

The top floor featured guest rooms for visitors (sans private bath, as was the custom of the day) plus the relatively modest homes of the Harvard Monthly and Harvard Advocate.