Goeffrey Ward

The following is an illustrated transcript of Geoffrey Ward’s talk for the Sixth Annual FDR Memorial Lecture given this past May. Eds

My grandfather was a life-long Republican, always proud to have cast his first presidential vote for Theodore Roosevelt. To him, Franklin Roosevelt was a lightweight, a pale imitation of the vigorous, voluble hero of his youth.

My father, a life-long Democrat, was proud to have voted four times for Franklin Roosevelt. To him, Theodore had been nothing more than a perennially excitable adolescent, shrill and insubstantial.

They were both wrong. That’s the essential premise of the Ken Burns seven-part, fourteen-hour series, The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, that will run on PBS every evening for a week in September 2014. It makes the case that Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt had far more in common with one another than their contemporaries or my forebears ever understood, that it was the similarities and not the differences between them that meant the most to history.

As we say in the film, they belonged to different parties and overcame different obstacles. They had very different temperaments and styles of leadership. But both were children of privilege who came to see themselves as champions of the workingman — and earned the undying enmity of many of those among whom they’d grown to manhood.

They shared an unfeigned love for people and politics, and a firm belief that the United States had an important role to play in the wider world.

Each displayed unbounded optimism and self-confidence, each refused to surrender to physical limitations that might have destroyed him, and each developed an uncanny ability to rally men and women to his cause.

Both were hugely ambitious, impatient with the drab notion that the mere making of money should be enough to satisfy any man or nation; and each took unabashed delight in the great power of his office to do good. To both of them, the federal government was, as Theodore Roosevelt liked to say, “us.”

Our television series focuses on all three great Roosevelts – Theodore, Franklin and Eleanor, who was TR’s niece as well as FDR’s wife -– but since she could not have attended Harvard had she wanted to, I’m setting her aside this afternoon to focus on some of TR and FDR’s experiences here in Cambridge, experiences that hint at the differences as well as the similarities between the ways they would one day face the world beyond it.

I’d like also to set aside at the outset the impact on the Roosevelts of the formal, educational side of their Harvard careers. Biographers have spent a lot of time seeking important connections between what they were taught and how they governed. It’s a largely fruitless search.

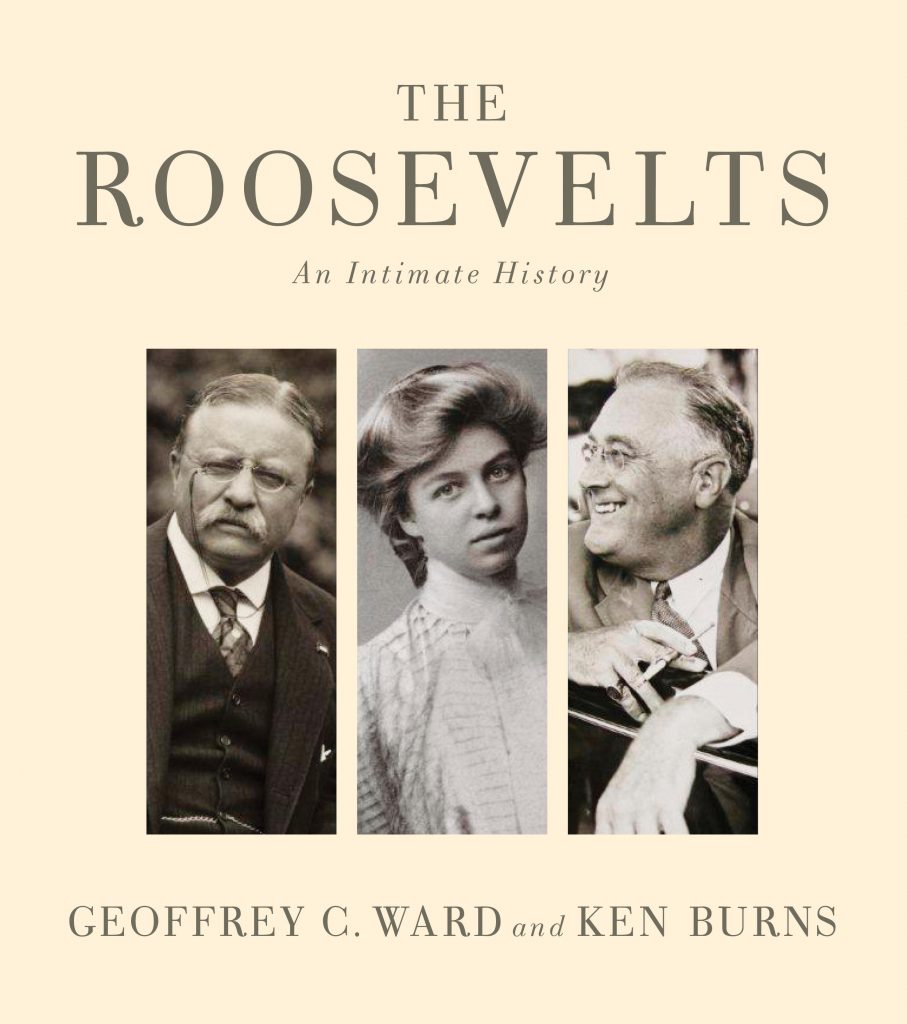

TR as a Harvard freshman

Theodore Roosevelt came to Harvard determined to become a biologist and shifted to politics in part because he found the science he was taught in Cambridge so unrelentingly bloodless. He didn’t get much out of his classes in political economy, either: “I was taught the laissez-faire doctrines … then accepted as canonical,” he recalled. “But there was no teaching of the need for collective action, and of the fact that in addition to, not as a substitute for individual responsibility, there is a collective responsibility.”

That is not to say that Theodore Roosevelt didn’t learn a great deal at Harvard — just that the classroom seems to have had little to do with it. He learned a great deal everywhere; he had a near-photographic memory and limitless curiosity, was rarely seen without a book even as president.

“I thoroughly enjoyed Harvard,” he remembered, “and I am sure it did me good, but only in the general effect, for there was very little in my actual studies which helped me in afterlife.”

Franklin was less forthright than Theodore – in this as in most things – but he did once privately complain to his roommate, Lathrop Brown, that his studies had been “like an electric lamp that hasn’t any wire. You need the lamp for light, but it’s useless if you can’t switch it on.” In all his cheerful, chatty, carefully opaque letters home from Cambridge there is not one word about the content of his classes.

When he was in the White House and one of his Republican classmates mused to a reporter that the New Deal would have been very different if Roosevelt had only taken more economics and government at Harvard, FDR shot back, “I took economics courses in college for four years, and everything I was taught was wrong.” The appeal of systematic or abstract thought would remain a mystery to Franklin Roosevelt all his life.

The two Roosevelts shared other experiences as undergraduates. Each lost his father while at Harvard, each courted his future wife during his time on campus.

Both were embarrassed by family scandals, too. Theodore’s cousin Cornelius appalled his relatives by marrying a French actress, a choice so unthinkable that a compiler of the family genealogy thought it best simply to report that he had been “married in Paris” and not mention the bride’s name at all.

Franklin’s older half-nephew, James Roosevelt Roosevelt, Jr. – known by the family as “Taddy”– made headlines by disappearing from Cambridge in his sophomore year and then turning up married to a New York prostitute nicknamed “Dutch Sadie.” “One can never again consider him a true Roosevelt,” Franklin wrote home. “It will be well for him not only to go to parts unknown, but to stay there and begin life anew.”

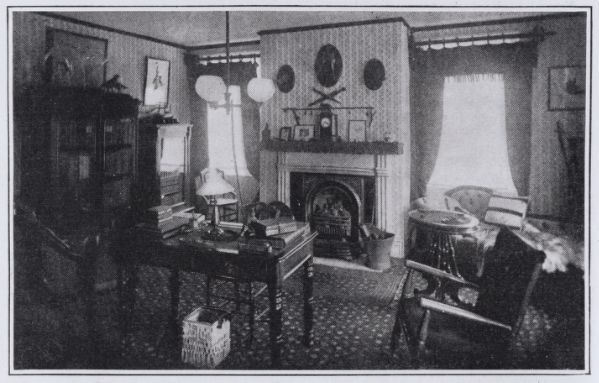

TR’s Room While At Harvard. The private rooming house was located where the Malkin Athletic Center now stands.

Theodore Roosevelt’s college life, his sister Corinne remembered, did “what had hitherto not been done, which was to give him confidence in his relationship with young men of his own age.” He’d really had virtually no contact with young men of his own age before he descended on Cambridge in the fall of 1876; severe and recurring asthma had kept him in the care of tutors and out of the classroom.

One classmate remembered him as a “bundle of eccentricities” when he first arrived. He kept stuffed birds and live snakes in his rooms on Winthrop Street. An enormous tortoise escaped its cage one day, wandering into the kitchen to terrify his landlady.

The eight hundred privileged students of Harvard College, two thirds of whom came from Boston or its surrounding towns, then cultivated an air of elaborate indifference; they affected an indolent saunter called the “Harvard swing,” and a languid way of speaking, the “Harvard drawl.”

Theodore Roosevelt was incapable of being either indifferent or languid, even for a moment. “When it was not considered good form to move at more than a walk,” an acquaintance remembered, “Roosevelt was always running.” He was always talking, too, with such staccato vehemence that some believed he had a speech impediment, and so often that his geology professor felt he had to stop him: ”See here, Roosevelt,” he said, “let me talk!”

Teddy’s Harvard: This 1874 view, taken from the newly completed Memorial Hall tower, looks south down Quincy Street, then called Professors Row, towards the Charles. Sever, Emerson and Robinson replaced these buildings. Gore Hall, the Gothic predecessor to Widener, stands to the far right. Just beyond to the right, the only familiar building in Boylston Hall

His unshakable belief that he always occupied the moral high ground did not endear him to his fellows, either. The father he all but worshipped sent him off to college with a stern admonition: “Take care of your soul, then of your health and lastly your studies.” “Thank Heaven,“ he wrote in his journal toward the end of his college career, “I am perfectly pure.” He was angry if a fellow-student dared curse in his presence and only once is known to have had too much to drink – at the dinner welcoming him to the Porcellian Club. “Was ‘higher’ with wine than ever before – or will be again,” he noted the next morning. “Still, I could wind my watch.” Then he added, “Wine makes me awfully fighty.”

So did other things. In his freshman year he had to be restrained from leaving a Republican procession to pummel a Democratic upperclassman who had dared hurl a potato at him and his fellow-marchers. At a campus party two years later, according to his diary, “I got into a row with a mucker and knocked him down; cutting my knuckles pretty badly against his teeth.” And when he thought Alice Lee, the lovely girl from Chestnut Hill whom he had begun to court, might have another serious suitor, he ordered a brace of dueling pistols from France and a cousin had to be dispatched from New York to disarm him.

“He was his own limelight, and could not help it,” an underclassman remembered. “A creature with such a voltage as his, became the central presence at once, whether he stepped on a platform or entered a room – and in a room the other presences were likely to feel crowded, and sometimes displeased.” There were those who shared the opinion of William Roscoe Thayer who was a class behind him that Roosevelt was “a good deal of a joke … active and enthusiastic and that was all.”

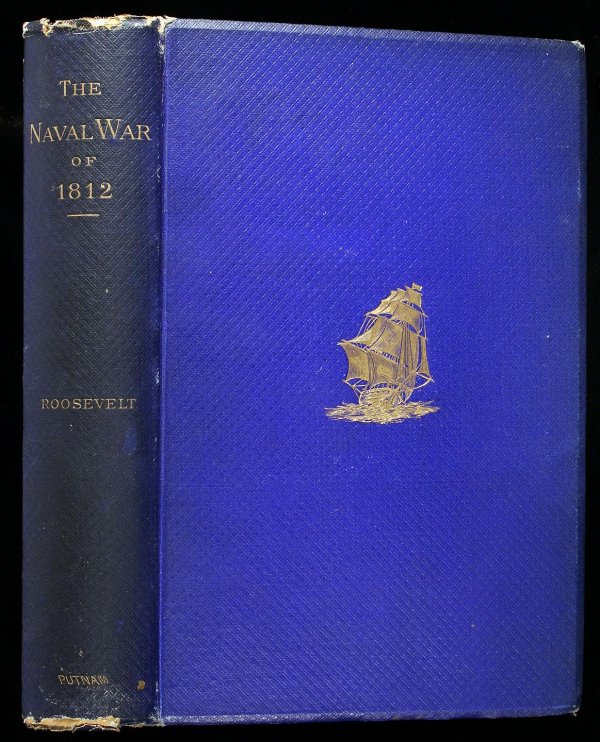

But by and large, for all the noise he made, all his eccentricities, all the overwrought emotion and self-regard he sometimes displayed, Theodore Roosevelt triumphed at Harvard. In June of 1880, he was graduated magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, twenty-first in a class that began with 230 students, and he had already – while still an undergraduate and on his own initiative — completed two chapters of what would one day be considered a definitive Naval History of the War of 1812.

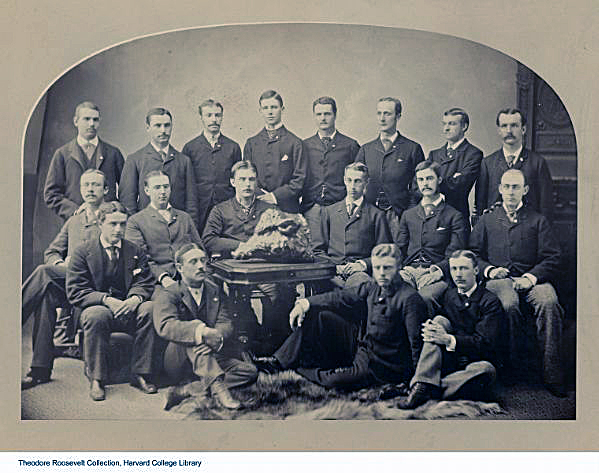

Just as important in his own eyes – and in those of his contemporaries – were his social triumphs. He was elected to many of the most prestigious Harvard organizations – organizations that to an outsider trying to understand their workings still seem as exotic and mysterious as the Illuminati or the Rosicrucians – the Institute of 1770, Hasty Pudding, the Dickey – and, most exalted of all, Porcellian. In the end, he remembered, he had won the respect of his fellow students, by being a “corking boxer, a good runner, and a genial member of the Porcellian Club.”

“My career at college,” Theodore Roosevelt wrote upon graduation, “has been happier and more successful than that of any man I have ever known.”

Franklin Roosevelt was never quite able to make that claim. The roots of his puzzling dissatisfaction with his performance at Harvard stretch back to his pampered boyhood in Hyde Park. More than most boys, he had been the object of universal admiration and affection – from his parents and grandparents and their friends, from the legion of nurses and governesses hired to see to his every need, as well as from his father’s tenants who doffed their caps to “Master Franklin” as he rode past on his pony. It had been the natural order of things that he be liked by everyone, and he had worked almost desperately to replicate that world at Groton. His teachers liked him – he’d been raised to please grownups – but many of his schoolmates did not: he was too slight for athletic distinction, too well-read and well-mannered, too eager to please. Something had gone “sadly wrong” at Groton, he told his wife; to a close friend he admitted he’d “always felt entirely out of things.”

Teddy Roosevelt, first row 2nd from right, and his fellow Porcellian members. FDR never forgot that “Cousin Ted” made the Porcellian, while he was blackballed.

He determined to do better at Harvard and by any objective standard he did. He belonged to the Institute, Hasty Pudding, the Signet Literary Library Society, the Memorial Society, the Glee Club, the Fly Club, was chosen chairman of the 1904 class committee and elected president of the Crimson, an influential post he enjoyed so much he enrolled in graduate school and stayed an extra year on campus rather than give it up.

But two defeats profoundly shook him. He had wanted above all to be asked to join Porcellian. Theodore Roosevelt, whose meteoric rise to power he already hoped to emulate, belonged. His own late father had been an honorary member. The sixteen members who would decide whether or not to invite him to join included five men who had known him at Groton. But someone blackballed him. He was never sure who had done it, was never told why. All he knew was that just as at Groton, he had unaccountably been barred from the exalted position his childhood training had taught him should be his without effort. Then, in his senior year, he was denied the most prestigious honor his class could grant – the chance to be one of just three class marshals. Six men were nominated, himself included, but the election was be rigged. Twenty-seven years after Theodore Roosevel’ts arrival at Harvard, Bostonians still ran things; the top clubmen had quietly agreed on their own three-man slate. FDR came in fourth.

His perceived failures at Harvard seemed to haunt him. When he attended the White House wedding of Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter, Alice, he was allowed to arrange her bridal train for the official photograph, but had to pretend not to be bothered when the bride’s father, the groom and the groomsmen withdrew into the private dining room and closed the door so that they and their fellow Porcellians could toast the bridegroom and sing club songs in private.

When Franklin’s own engagement to the president’s niece was announced, the newspapers focused on her – and identified him as a member of the New York Yacht Club who “had been defeated in a close struggle for election as a class day officer.”

FDR would remain a loyal son of Harvard , though his zeal never matched that of the father of his roommate Lathrop Brown, who, whenever he passed through New Haven with his three sons, ordered them all to get out and spit on the platform. Roosevelt attended as many Harvard-Yale Games as he could manage, and stayed so late so often at the Harvard Club in Manhattan that his wife angrily complained. And he would eventually be proud that three of his four sons attended his alma mater — and that all three were asked to join his club, the Fly.

But his disappointment at not being asked to join Porcellian and his defeat for class marshal continued to rankle. He remained convinced that a cabal of Boston-based clubmen had conspired to defeat him, and on the eve of his class’s tenth reunion in 1914, he sought to break their grip. He lobbied hard to have friends who, like him, lived in New York and elsewhere – he called them “westerners”— elected to the planning committee. The Bostonians easily outmaneuvered him and appointed instead an “executive committee composed of the Boston men who will have full power and carry out all details,” thereby crushing what one alumnus called “our bolshevik revolution.”

Outwardly oblivious, as always, he continued regularly to attend Harvard events as if nothing awkward had happened. In 1917, Harvard alumni elected him to the Board of Overseers; distrust and dislike of him was still largely confined to members of his own class.

Former Harvard roommate and Groton friend Lathrop Brown with FDR aboard a destroyer, ca. 1915

He was Assistant Secretary of the Navy when his 15th reunion was held at New London, Connecticut two years later, and he arranged to receive his classmates on the deck of a destroyer, a setting which even some of his old friends found unduly showy. He was still trying too hard. “At lunch on the second day, Franklin made his grand entrance,” one recalled. “He had that characteristic way of throwing his head back and saying, ‘How are you Jack?’ and ‘How are you Walter?’ and ‘How are you Arthur?’ I know I had the feeling, ‘Hell, Frank. You can’t put on all that stuff with us, we knew you from the old days.’”

Later that same year, returning from the Paris peace talks with president Woodrow Wilson, FDR confided to Theodore Roosevelt’s nephew, W. Sheffield Cowles, Jr., that his rejection by Porcellian had been “the greatest disappointment in my life.” Cowles was astonished. “I thought he was quite successful,” he remembered. “After all, as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, he rated a nineteen-gun salute.” By then, insult had been added to injury; Theodore Roosevelt’s sons, Theodore, Jr. and Kermit, had been admitted to the club that had barred him.

After being crippled by polio in 1921, he would never again walk unassisted.Four years later, polio seemed to end his political career. Even classmates who had been scornful of him wrote to express their sympathy. They sympathized with his arduous seven-year struggle to regain his feet, as well. Most applauded him for his brave return to politics in 1928. And when it came time for his 25th class reunion the following spring, Harvard itself chose to honor him both for having won the governorship of New York and for the courage he had displayed in winning it, by conferring on him nearly all the honors it could bestow.

A rare picture showing FDR standing with crutches.

It was one of the high points of his life. A quarter of a century after he’d left Cambridge, disappointed that he’d somehow failed to become the kind of universally acknowledged leader he’d been raised to believe he should always be, he really was the focus of everyone’s admiring attention. He was awarded an honorary Phi Beta Kappa key and when he began his slow, careful way onto the stage of the auditorium (where he had once heard Theodore Roosevelt speak), gripping the arm of his eldest son, James, and leaning heavily on a cane, the audience rose to its feet, cheering.

He was given an honorary doctor-of-laws, too – with what must surely have been one of the most wildly inaccurate citations in academic history: Franklin D. Roosevelt, it said, was “a statesmen in whom is no guile.“

But best of all, from Franklin’s point of view, his classmates chose him for what he saw as the supreme honor – Chief Marshal of the Commencement. “It certainly is grand,” he told one of his closest Harvard friends. “I assure you that being Governor is nothing in comparison.”

The honeymoon did not last. Recognition of Roosevelt’s courage was one thing. Voting for him was another. When he ran for president in 1932, a campus straw-poll showed overwhelming support for Hebert Hoover. The Crimson was soon calling FDR “a traitor to his fine education,” and by the time the Harvard tercentenary came around in the midst of his campaign for re-election in 1936, the necessity of inviting the university’s best-known alumnus back to Cambridge had become something of an embarrassment. “Perhaps those who have told us that educated men should go into politics were on the wrong track,” said the editorial board of the Crimson. “In the midst of our great Three Hundredth Anniversary, let the presence of this man serve as a useful antidote to the natural overemphasis on Harvard’s successes.”

Harvard’s ex-president, A. Lawrence Lowell, was in charge of the celebration. He had taught FDR constitutional government as an undergraduate – and, from his point of view, had clearly failed miserably. He was now determined to minimize the president’s role in the day’s ceremony as much as possible. In an extraordinarily patronizing letter of invitation he addressed his former student simply as “Mr. Franklin D. Roosevelt,” urged him to use the occasion to “divorce” himself from “the arduous demands of politics and political speech-making” — and asked that he limit his remarks to ten minutes.

Roosevelt was livid. He was the president of the United States, he told his friend and fellow alumnus Felix Frankfurter, and he badly wanted to tell Lowell that if he were being asked to speak for the Nation in that capacity “I am unable to tell you at this time what my subject will be or whether it will take five minutes or an hour.”

Frankfurter drafted a less aggrieved response for the president to send and in the end FDR did limit his address to ten minutes. But in his opening remarks he did not so much as acknowledge Lowell’s presence. On Harvard‘s two-hundredth anniversary, he said, “many of the alumni were sorely troubled concerning the state of the Nation. Andrew Jackson was president. On the two hundred fiftieth anniversary of the founding of Harvard College, alumni again were sorely troubled. Grover Cleveland was president. Now, on the three hundredth anniversary, I am president.”

Harvard, he continued, could be counted on to produce what he called “its due proportion of those judged successful by the common standard of success.” But he wanted it to do more: “Harvard should train men to be citizens in that high Athenian sense which compels a man to live his life unceasingly aware that its civic significance is its most abiding, and that the rich individual diversity of the truly civilized State is born only of the wisdom to choose ways to achieve which do not hurt one’s neighbors.”

A seemingly jovial FDR chats with old friend and classmate Grenville Clark at the Harvard Tercentary in 1936. In reality, his crippled legs kept him locked in his chair for hours during a cold, steady rain.

Roosevelt was received politely, but Harvard attitudes toward him had not changed. (He may have taken some small comfort from the fact that Harvard had not always approved of Theodore Roosevelt either: TR had been an Overseer when he dared run for president as a Progressive in 1912, splitting the Republican party and ensuring the election of Woodrow Wilson. When he arrived for a meeting, his fellow-Overseers turned their backs on him.)

Mike Reilly, the head of FDR’s Secret Service detail, remembered that he heard his boss booed just twice during the twelve years he was at his side. Both occurred during the 1936 campaign. The first came just two weeks after the president spoke at Harvard, as his motorcade passed through Manhattan’s financial district. Roosevelt shook it off, smiling and waving as if he hadn’t heard it. He did not expect cheers from Wall Street.

But on October 21, as he drove through Harvard Square on his way to deliver a speech in Worcester, undergraduates lined the street to jeer him. “That hurt him, and his face showed it,” Reilly remembered, “He was always very proud of his Harvard career…”

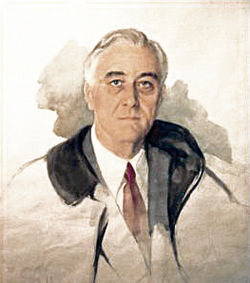

The unfinished portrait of FDR by Elizabeth Shoumatof

As Roosevelt’s attention turned from the ongoing economic crisis at home to the mounting crises abroad, Harvard’s opinion of him softened. In the end, most alumni came to fear Hitler more than they deplored the New Deal. “Mr. Roosevelt, as he grew older, grew into younger hearts,” wrote the editor of the Harvard Bulletin after the president died in the spring of 1945. “He was a symbol, a cause, a reason, and an anvil of strength to youth. He was the only president this fighting generation has ever consciously known.”

Roosevelt’s almost wistful affection for his alma mater had remained constant literally to the day of his death. He was to pose for a portrait that morning in his cottage at Warm Springs, Georgia and, because he wanted to look his very best, he instructed his valet to lay out a fresh white shirt, a grey double-breasted suit – and his red Harvard tie.

Copyright Geoffrey C. Ward 2014. Used by permission.