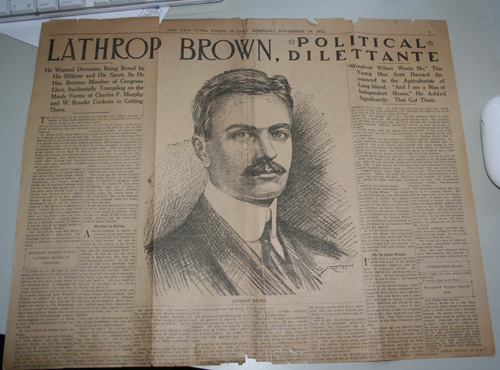

In this the third in a series of articles on FDR’s longtime friend and Harvard roommate, Lathrop Brown, we take a break from the Pare Lorentz interviews to focus a bit on Brown’s own political career. While FDR battled his way into the New York State Assembly, LB also (coincidentally?) became interested in politics, as the following article, taken from the New York Press, Sunday November 10, 1912, amply describes. An original copy of this piece was donated to Foundation by Pam and Elmer Grossman, LB’s grandaughter and grandson-in-law. The text is so rich, and so much of the period, that I’ve quoted it here in toto, illustrating the article with photos from various sources including the private collection that the Grossman’s have generously shared with the FDR Foundation.

LATHROP BROWN POLITICAL DILETTANTE

He Wanted Diversion, Being Bored by His Millions and His Sport, so He Has Become Member of Congress-Elect, Incidentally Trampling on the Manly Forms of Charles F. Murphy and W. Bourke Cockran in Getting There

“Woodrow Wilson Wants Me,” This Young Man Announced to the Agriculturalists of Long Island. And I am a Man of Independent Means,” He Added Significantly. That Got Them

The fervid desire of Mr. Lathrop Brown of New York, Harvard and St. James to do something that he had never done before has resulted in tumbling him into the next Congress.

Mr. Brown didn’t really want to go into the next Congress, at least not so soon. He wanted only to be a politician instead of a society man and he finds himself a statesman-elect, the choice of the farmers of the First Congressional District of the State of New York – the farmers who inhabit Long Island between the 34th Street Ferry landing and Montauk Point, and raise potatoes, cabbages, and other flowers.

The original article donated by Pam and Elmer Grossman. This copy will be preserved in the Harvard University Archives

Incidentally he played Ivanhoe to the Bois-Guilbert of Charlie Murphy and drove that dread knight shrieking from the plains of Suffolk. Also incidentally, if Colonel Roosevelt wants any Government cabbage seeds for his Oyster Bay garden next year and goes about getting them in the routine way, he will have to address his humble plea to the Hon. Lathrop Brown, House of Representatives, Washington D.C. as the Colonel’s home is in Mr. Brown’s Congressional District. Colonel Roosevelt may think he has a pull with the Congressman-elect, for the reason that the Colonel’s brother-in-law, Douglas Robinson, is the business partner of Charles S. Brown, who is the happy father to the Hon. Lathrop Brown.

But the Colonel may find Representative Brown a stern man. His campaign posters have committed his fealty to Princeton. They announced flatly: WOODROW WILSON WANTS LATHROP BROWN IN CONGRESS. It stuck out in big type on three sheets scattered from Miller’s saloon in Long Island City to the Montauk Lighthouse, and from Long Beach to the Wheatley Hills. It impressed the Long Island voter. It told him as plainly as type can tell that that must be a great yearning with Woodrow Wilson. It seemed to say for the Princeton professor that, although he might be elected to the Presidency, he never would be happy unless he knew that Lathrop Brown was at the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, watchdogging he Treasury or using a neat nickel-plated reviser on the tariff.

So now Woodrow Wilson must be happy.

Among those who are left unhappy are Fred Hicks, who ran against Lathrop Brown on the Republican ticket, and W. Bourke Cockran who ran on the Progressive ticket. And it all happened because Mr. Brown was bored. Fed full and surfeited with all the joys that money and good looks can bring to a young man, he bounded into politics because it was the only field left unconquered.

Helen Hooper Brown, aged 16. At 15, she became a millionairess orphan, and promptly hired herself a governess, setting off to Europe to complete her education – the first of many signs of an extremely independent nature. Courtesy Pam and Elmer Grossman

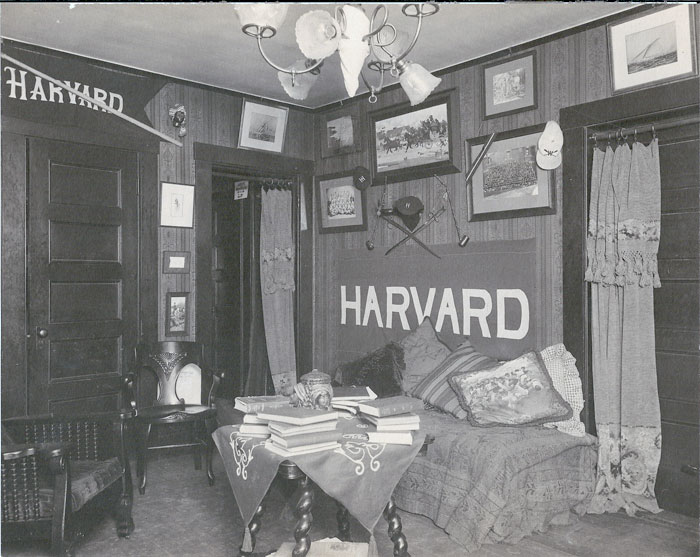

It is a terrible thing to discover, at age 30, that life has no new sensations to offer. Mr. Brown found himself almost in this predicament. He had his career at Harvard, with wonderful success in Greek and the germans. He indulged in athletics to the extent necessary to keep him in perfect trim. After the college years he had so much social life in New York that it palled on him. Sport always appealed to him, and he was well known wherever good horses were to be seen, whether on the racetracks or in the hunting field. He owned several good jumpers and raced them with success.

Two years ago Mr. Brown married Helen Hooper of Cambridge Massachusetts, an heiress to the great Ames estate to the extent of $10,000,000. She too is fond of horses, for her father formerly owned, under the racing name of ‘Mr. Chamblet,’ one of the greatest stables of jumping horses the American turf has seen.

So Mr. Brown and his bride decided to settle down in a country where good horses could be enjoyed. They bought an estate of 100 acres on St. James Harbor, not far from the home of Mayor Gaynor.

His Start In Politics

A millionaire in search of pleasure of the good healthy sort can find it in infinite variety in that section. He has the Sound for the racing of his motorboats, a fine beach for swimming, the bay and the Nissequoque River for fishing. In the fall he can shoot ducks in the Smithtown Bay until his gun barrels get red hot. On his own acres he can shoot partridge, quail, and the fat English pheasants they bred in that region. There is a fine field for polo and horse racing. His motor cars can skim over roads that are perfect. His eye rests on scenery as beautiful as the North Woods can boast of.

The Brown Home, 'Land of Clover' at St James, Long Island. This Colonial Revival structure was designed by Lathrop's brother Archibald Brown '02, a noted architect. The estate's unique circular stable, based on classical precedents, housed 22 horses. 'Land of Clover' was the first in a long series of spectacular homes built – but sometimes not occupied, like this one – by the Brown family. The house and stables are still extant, known today as the Knox School, which not unexpectedly, is popular for its equine program.

Lathrop Brown enjoyed every one of these things, but, somehow, they did not seem to fill his soul. Perhaps he sight of his neighbor, Mayor Gaynor, rushing away from Deepwells to his work in the city suggested a new pleasure – politics and the activity thereof.

One night Mr. Brown dropped in on the village storekeeper, who was the local Democratic committeeman.

“How,” he asked, “do you get voters out in a Presidential year?”

“Why,” said the committeeman, “they just come out. And if they don’t come out, it’s their own fault.”

“Why doesn’t your state committeeman make them come out?” asked Mr. Brown.

“I guess you’ll have to ask Charley Murphy about that,” was the reply. “He bosses the state committeemen.”

Mr. Brown grew more interested. He knew that Mr. Murphy’s address was 14th street, Borough of Manhattan. What could he have to do with the wilds of Suffolk? He inquired about it.

“Why,” he was told, “Murphy has a summer home out at Good Ground and he thinks that gives him the right to own our State committeeman.

Lathrop Brown made his decision at once. He would have a new sensation. He would battle with Charles Francis Murphy for the supremacy of the Long Island wilderness and he would come back with his shield, or on it.

He unlimbered his snickersnee and put ten gallons of gasoline in the sixty-horse power car he drives himself. He filled his pockets with cigars such as Suffolk county never had smelled before. He kissed his wife and child farewell and fared forth.

He took the old Democrats of Suffolk County by the ends of their beards and led them from their inglenooks out into the sunlight. “We’ve got a Presidential election coming on,” he cried. “What are you going to do about it?”

They hadn’t thought anything about it, he discovered.

“Get busy!” he cried, and proceeded to set an example. He gave diners for the older men of the party and organized clubs for the younger set. In a month he had them properly aroused, and then he confided to them that he was going to whale C. Murphy, just as the preliminary gallop before the Presidential race.

Later, the Browns would buy another Long Island property 'The Windmill' on Montauk Point. The house was so named for the 1813 windmill Lathrop had moved from Southhampton and re-erected on his property, using the structure as a guest house. When the site was taken over by the Army during WWII, the windmill was moved again to Wainscott, where it still exists.

Bailey was the State committeeman for the district, and he was Murphy’s man. Mr. Brown couldn’t [waltz] into Fourteenth Street and tap Mr. Murphy on the skull with a blackjack; that isn’t proper political procedure – but he could make open war on Bailey.

And he did. He picked up Harry Keith for his candidate. Keith is a Democrat who frequently had opposed Bailey, but always got trimmed when he came before the Committee on Credentials. That’s old Tammany stuff. The late Senator Grady said that “the dirtiest day’s work of his life” was done as the chairman of a Committee on Credentials.

Mr. Bailey ran to Mr. Murphy and told him that his job as Street committeeman was in peril. Mr. Murphy loves to own State committeemen and he felt that he could ill afford to spare one. He learned that Mr. Keith held a State job. Mr. Keith lost his State job the next day. He laughed, because Lathrop Brown laughed.

“Coarse work” said Mr. Brown. “That will win us a lot of votes in the primaries.”

It did. Keith won the primaries. Bailey made the customary bluff at a contest. For every lawyer that turned up in his interest, Mr. Brown turned up with three. For every dollar Bailey had to spend to make a contest, Keith turned up with five.

The Lathrop Brown windmill, now in Wainscott, Long Island.

Some kind friend took Mr. Murphy aside and told him that Brown was ready to play politics as Commodore Vanderbilt played poker.

“Let that fellow alone,” said the counselor. “Brown has more millions than you will ever have. And he stands all raises and calls all bets.”

Keith is the committeeman.

Lathrop Brown now turned to the job of electing Wilson. He visited the editor of almost every Democratic newspaper in Suffolk and Nassau counties and talked Presidential triumph to him until the editor felt as important as Henry Watterson. He bought an interest in a newspaper in Port Jefferson and wrote its political editorials. He boomed Wilson for the nomination and screamed at the Democrats of the Island to wake up and get together.

So far as the political slates were concerned, Mr. Brown had everything his own way after Keith beat Bailey. But the wise young man let the conventions make their own choices. It so happened that these were usually his choices.

His the Laurel Wreath

It came time to nominate for Congress and some of the Brown enthusiasts suggested that he grab the nomination himself. Mr. Brown replied that grabbing was no fun for him. He was having the time of his life and he liked it. He wanted to be just a politician.

A lot of the Bailey-Murphy crowd wanted to see Brown nominated for Congress. When he ran Keith against Bailey they said Brown was a joke and they kept on saying it until the State Committee was forced to take Keith to its bosom. Now, if they could get Brown to take the Congress nomination, they could say that that was a joke. They didn’t think that Brown or any other Democrat could win.

Two years ago the district upset all political traditions by electing a Democrat, Martin W. Littleton, over William W. Cocks, who had been the Republican Representative for some years. Littleton, who didn’t live in the district at all, went into the fight mostly to help out the State ticket. His wife “Peggy O’Brien” helped him, and between them they turned the hard shell old district on its back.

All the wiseacres said it could never happen again; that Littleton, if he ran this year, would be beaten. The district is made up of part of the County of Queens and all of Nassau and Suffolk. It runs from Long Island City to Montauk point, and contains farming district that is normally strongly Republican. Mr. Littleton told his friends that he wouldn’t run again unless he was sure of being beaten, for the reason that going to Congress put a large crimp in his law practice.

With Littleton out of the field Mr. Cocks wanted to try his hand again, but the Republican convention turned him down and nominated his brother Fred Hicks. This may sound queer, but it’s true. When Fred Cocks was very young he was adopted by a rich Long Islander, Mr. Hicks, and became his heir. The Progressives nominated former Representative Bourke Cockran.

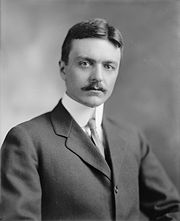

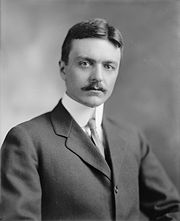

Lathrop Brown as Congressman. Brown ran again in 1914, but was defeated by handful of votes. The election was contested all the way to the New York Supreme Court, and his opponent, Frederick Hicks, was not seated until late in his term.

The Democratic situation was very much up to Lathrop Brown. His friends urged that, with the Republicans split, he might win. Brown had intended to ascend the political ladder by easier stages; possibly with a term or two in the Assembly of the State Senate. He had heard that there was plenty of action to be had in Albany. In the end his partisans seized him and bound the laurel wreath of nomination to his brow. He took it.

Brown’s campaign circulars provided welcome reading for the Democrats of Long Island. No one could mistake wording like this: “Mr. Brown is a man of independent thought, independent action, and independent means.”

They had read circulars before from office seekers who boasted of independent thought and action, but that INDEPENDENT MEANS stuck right out and meant something new. It meant even more than WOODROW WILSON WANTS HIM.

And Brown was elected.

Lathrop Brown is a tall, lithe young man, with a small brown mustache, a ready smile and a pleasant address. He doesn’t dress too well, which helps some in politics in the country. Although very affable, he is also a very positive young man. He wants what he wants when he wants it, and he lets you know it. So far he has accomplished the most rapid political ascension that Long Island has ever observed, and performed the feat principally by stamping on the manly forms of Charles F. Murphy and the mellifluous Cockran.

For a political debutante, he is a wonder.