“Having a good time was of major importance in those days at Harvard. Customary procedure was to study for ten days with a tutor before an examination and never open a book for the rest of the time.” Lathrop Brown to Pare Lorentz, 1949

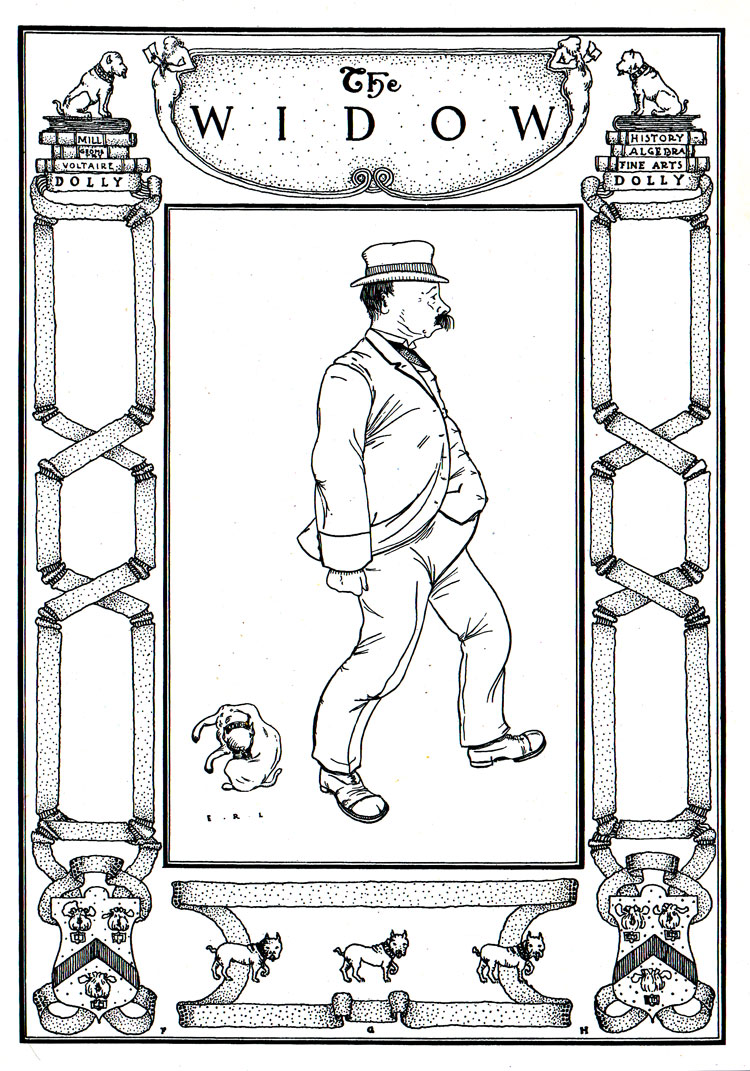

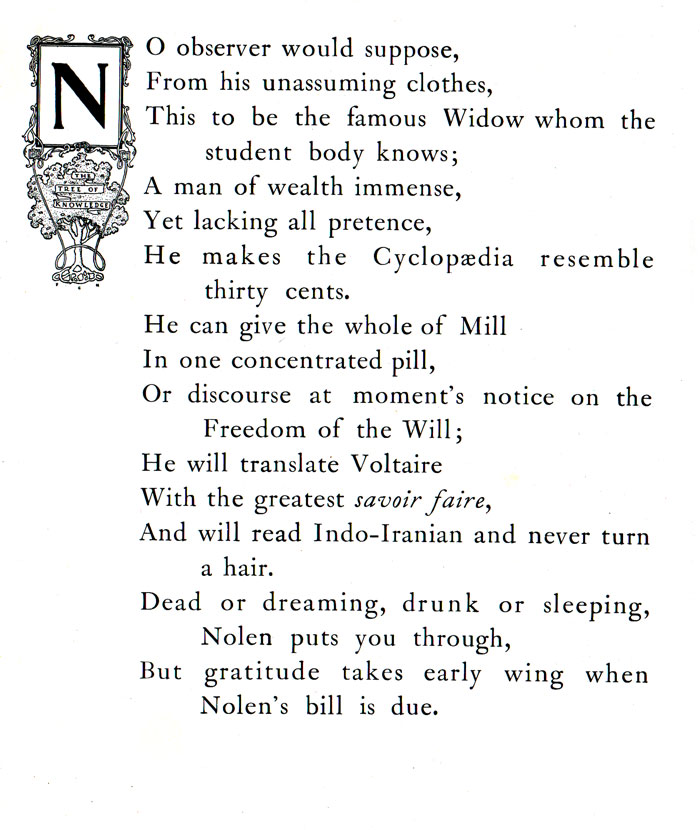

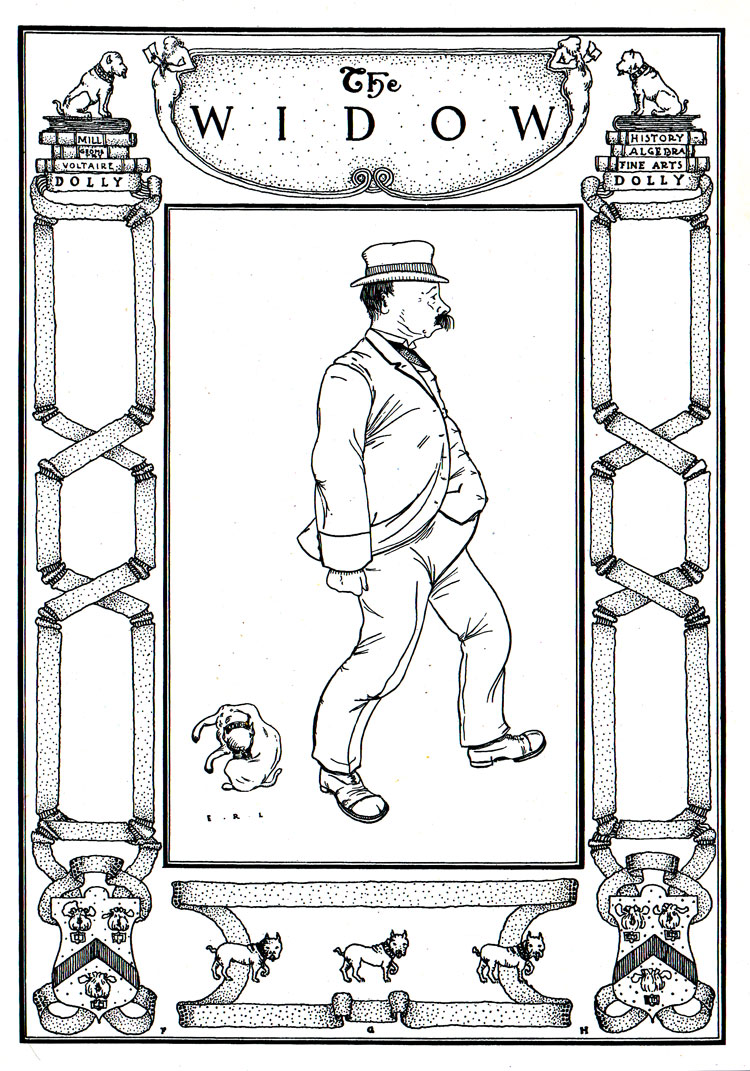

Over the last few weeks, as time and funds permit, I’ve been slowly framing a series of 16 prints we acquired last year, from a charming but extremely tattered 1903 volume entitled Harvard Celebrities. Written and illustrated by a classmate of FDR’s, this 30 page book parodies in picture and verse Harvard characters of the day. While some are still easily recognizable – Nathaniel Shaler, the famous naturalist, for example – others are far less so. Here’s one that I found intriguing:

Now from the text, and from Lathrop’s chance comment above, I had a general idea of who this might be, but imagine my delight when I discovered the following article from the October 1917 Independent, telling me not only who this was, but revealing a portrait of a Harvard long gone:

An Unofficial University Just Outside Harvard’s Gates

THEY call him “The Widow,” no one knows why. Whatever he is called he is, in his own single person, Harvard’s chief competitor. In moments of indiscreet candor members of the Harvard Faculty have confest that the college has tried, and tried in vain, every possible means of dislodging him—even to flattering him out of the way with the offer of a chair in the college. But he never could afford the honor. The highest paid professors in Harvard get a meagre $5000 a year. “The Widow” is reputed to enjoy an income of $20,000 a year—perhaps more. Nobody knows. [Editor’s Note: For comparison, Harvard Tuition in 1903 was $150 per year.]

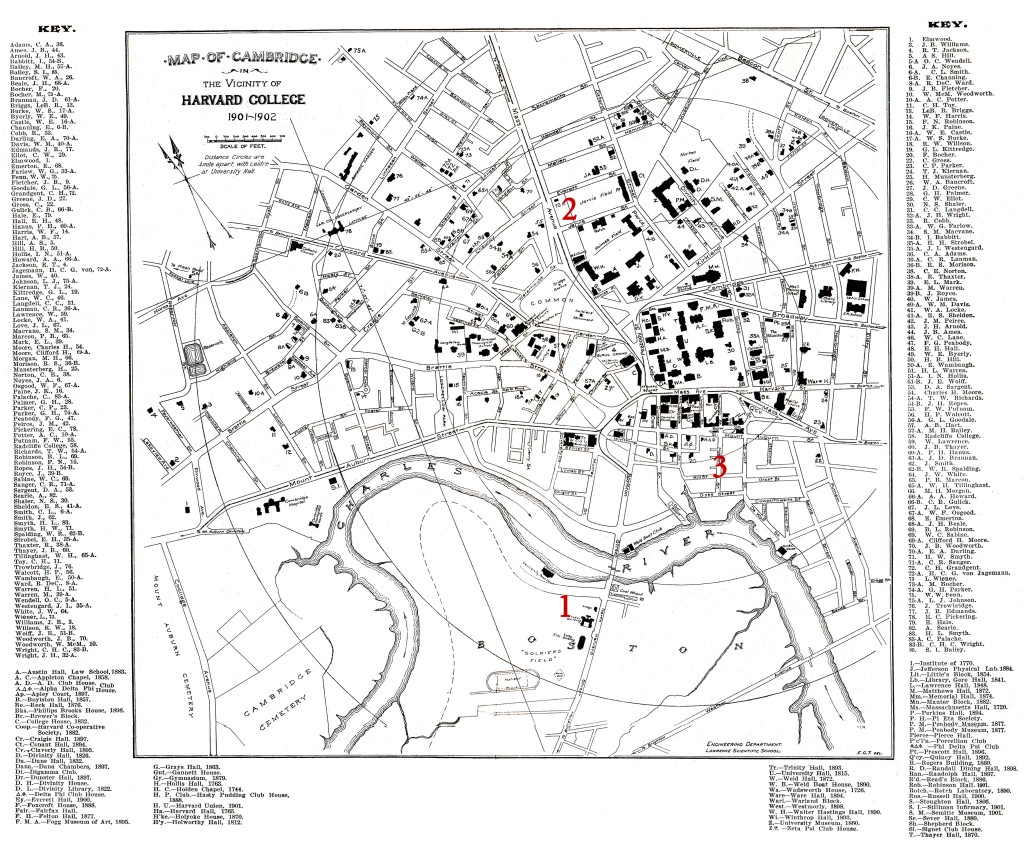

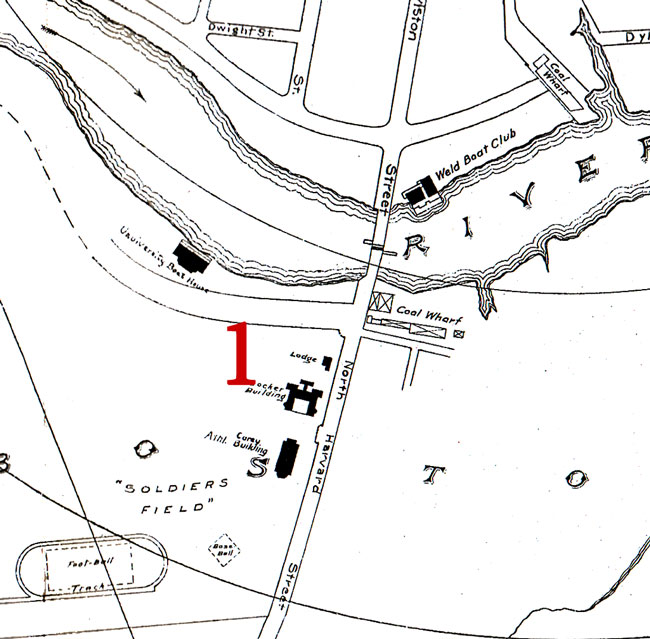

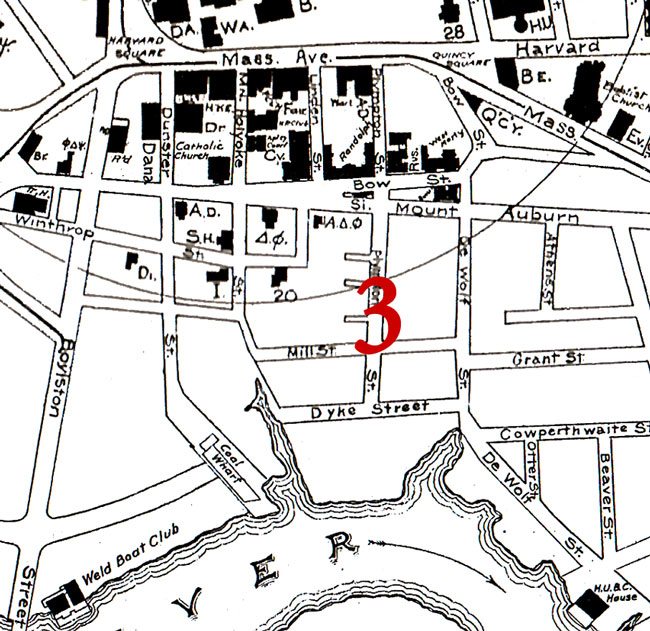

So he remains what he is—president of himself. For he is in his own university, with his own staff of fifteen professors, and his own dormitories, conveniently stationed just outside the famous Harvard “Yard.” The one concession he makes to Harvard is to permit his students the use of all of Harvard’s facilities—the Bursar, the Yard, the Gym, Soldiers Field, even the classrooms if they please. Even Harvard’s degrees. All “The Widow” pretends to supply is the best known substitute for a Harvard education.

If you find that it would be pleasant to be a Bachelor of Arts but for certain annoying obstacles in the way; if you find your studies interfering with the pleasures of the theater or the athletic field; if the exams are approaching and certain to find you embarrassed how to meet them; if you are the son of a rich man, a little spoiled and unaccustomed to work—what do you do?

You visit the Widow Nolen.

AND straightway you come under the eye of a remarkable man. Two generations of Harvard men know him, by reputation if not by personal experience of his bewildering fund of knowledge and his even more bewildering gift of handing it out to you in one exquisite, highly concentrated pill of information. In the Harvard records he is William Whiting Nolen, A.B. ’84. During five more years in the Graduate School he drew down an A.M. in ’86. Then to make a thoro job of it, he put himself thru the Law School besides. No one has discovered why he slighted the Medical School, the Dental School, the Veterinary School, and the Bussey Institute of Agriculture. Except for these trifling omissions, his education is fairly complete.

But in Harvard he learned much more than Harvard teaches deliberately. He learned, besides, the peculiar psychology of the Harvard professor. He learned how the Harvard professor teaches. Most important of all, to himself at least, he learned to gage, and with an accuracy that is uncanny, precisely what questions any given Harvard professor is most apt to ask.

Suppose an exam catches you a trifle innocent of history or literature. Suppose you have never dipped into some obscure book like “Vanity Fair.” To repair this natural oversight you join one of the Widow’s famous “seminars.” It is chiefly by these seminars that the Widow’s fame and fortune live.

These meetings are organized with wonderful psychological cleverness. Fifty students will be admitted to a room in the Widow’s establishment. The room is stark naked. Not a picture is on the walls to distract your eye. Not a sound is heard, except the Widow’s voice, to break your attention. You sit in silence with a pad of paper on your knee. Naturally every man jack in the room is frightened to death for fear of flunking, and the Widow begins with that advantage to himself.

HE needs no other advantage. No one sleeps when the Widow is speaking. One reason why his patients nearly always pass the desired exam is because the Widow has a marvelous faculty for making his talks interesting. Any professor might learn from him there. In an hour he will range over an entire history course. All he pretends to do is spot in the high lights, the main events, the leading figures. But it is all a wonderfully clear and compact digest of the course to be covered. Easy as this may be to remember, and remember even beyond the day of the examination, the Widow will finish by retracing his talk in a still more wonderfully clear and condensed conclusion.

In a literature course he will outline the periods and give the substance of every book required in the course. He will give you the message, the philosophy, the teachings of every author. And all this in the space of one hour! “Around the World in Eighty Days” reduced to sixty minutes! And yet the Widow has been known to lecture for five hours on end without a break.

In a complicated course he may supply a few “keys” for the memory, for he has invented a complete system of mnemonics. With almost hypnotic effect he will hang up a chart laying bare, say, the whole secret of a course in trigonometry. Or he may make the Word “Nawb” serve as a symbol for a whole period in history. A fool word in itself, it sticks in the memory by reason of that very fact, and faithfully bobs up in the mind during the exam, to stand for the names of Napoleon, Wellington and Bluecher, and their influence on the nineteenth century.

Or suppose a student on the eve of a German exam finds that he has opened nary a one of the books required for outside reading in the course. The Widow will welcome him to a cubicle in his establishment where he will be made comfortable with cigars or cigarets. The chair is restful. Everything is provided to leave the student’s mind open to treatment. Then in comes one of the Widow’s faculty of assistants. In the course of a single evening, while the student has nothing to do but sit back and drink it in and try to remember it all, this assistant will go thru that list of books and give a nutshell account of the contents of each one.

It is a college education in capsule form.

The one fault to be laid against a Nolen degree is that this mass of information is not guaranteed to stick in the mind for longer than the three hours of the examination. It is apt to be written on the mind in vanishing ink. Still, there is nothing to prevent a student from remembering it all if he can. The Widow charges his price and offers his commodity, to be taken how you please.

His income is his own business, but he certainly drives a thriving trade. If you want a whole evening with one of his assistants he will charge you $5 for the-services rendered. To join one of his hour-long seminars costs each man of the fifty present $2.50. And during the exam period the Widow and his faculty are busy day and night. Another of his rush seasons opens when the boys from the prep schools begin to congregate for the entrance exams. For these the Widow even maintains a dormitory, a nursery, for the fatherly care of the backward. It is a prep school in itself, with a course reduced to three or four weeks. For such services the Widow charges accordingly, with his prices based on the backwardness of the case. Since his patrons come mostly from the rich, his charges are probably in proportion.

Toward his assistants, however, he is reputed to be generous enough. He picks the brightest men he can get, and pays them well. You are taxed $2.50 for an hour with one of them, and of that $2.50 the Widow collects fifty cents. The $2 goes to the assistants.

OUTSIDE his crowded hours of tutoring Mr. Nolen finds time to indulge a nice taste in old furniture and objects of art—and his rooms are thickly strewn with superb specimens. And often, out of an income ample beyond his own simple needs, he exerts himself in behalf of the poor student. More than one man has had from Mr. Nolen other aids to a Harvard degree than great gobs of information only.

Such is the familiar figure of many jibes and of more caricatures than have been aimed at any other college celebrity

“Dead or dying, drunk or sleeping,

Nolen puts you thru; But gratitude takes early wings when Nolen’s bill is due.”

So runs a famous lyric lampooning the high tax that Nolen levies on laziness. And so he daily and serenely takes his stroll along the Charles, comfortable and corpulent, carelessly drest, with the never-absent Boston terrier that is almost as familiar a figure as he.

As a final aside, perhaps the aspect of all this I find most remarkable is that such levels of discovery are even possible. Ten years ago, before the age of the Internet search, only extreme good luck would have directed me to an Independent article a decade and a half after the fact, one citing the very book I held in my hands. But now, if you know how to frame the right question, a few staccato taps and clicks often yield the most astounding answers, from half a continent or more away.

Suddenly, the term “world-wide web” has true meaning.

I wonder what the old Widow would have thought about that…