Shortly after last year’s FDR dinner, I received an email from a certain Mr. Dave Robinson in Maine, inquiring as to whether or not we’d be interested in taking a look at some of the Harvard photos and ephemera he’d inherited from his grandfather, Chester Robinson, ’04, a friend and a classmate of FDR’s. I said certainly. Well, one thing led to another, I got busy, Dave got busy, then we made arrangements to get the materials scanned, then there was further delay, then mysteriously the ISB drive Dave sent me arrived empty: you get the general idea. Almost a year passed, and I still really hadn’t had a chance to see the extent of the collection.

The files arrived last week, and I opened them today.

Are we in for a treat!

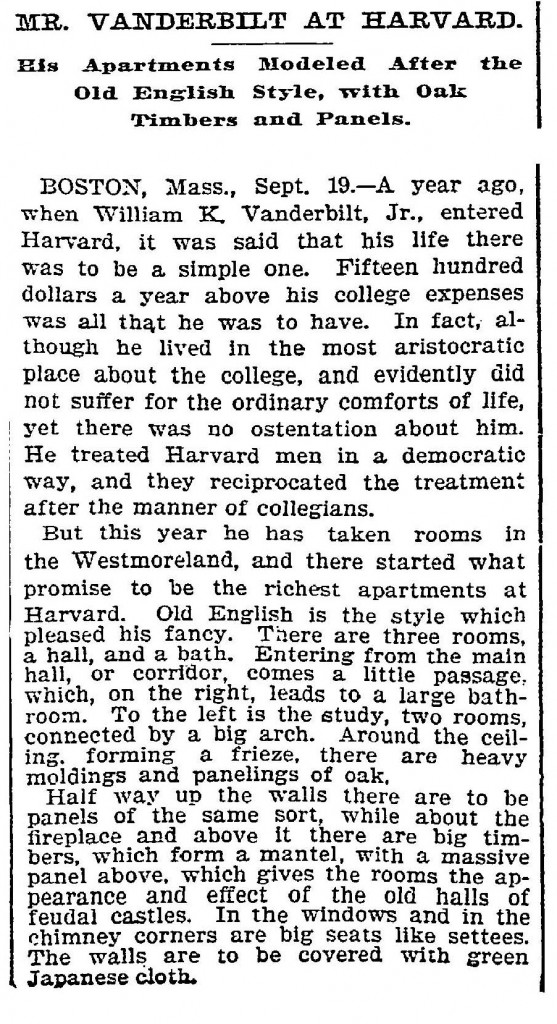

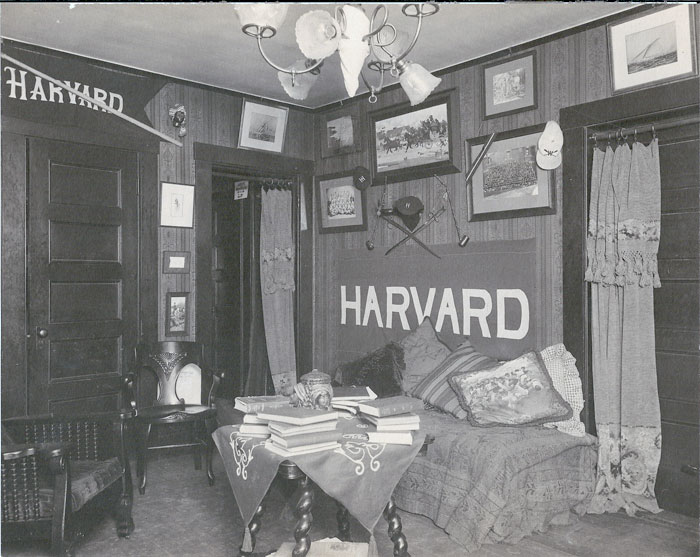

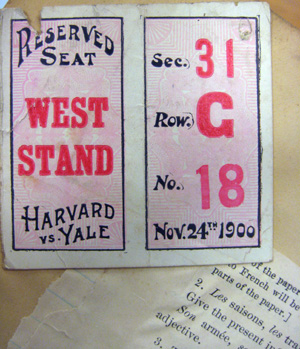

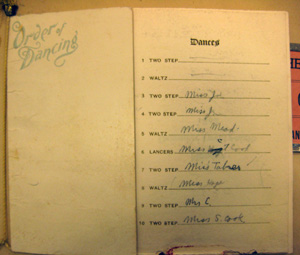

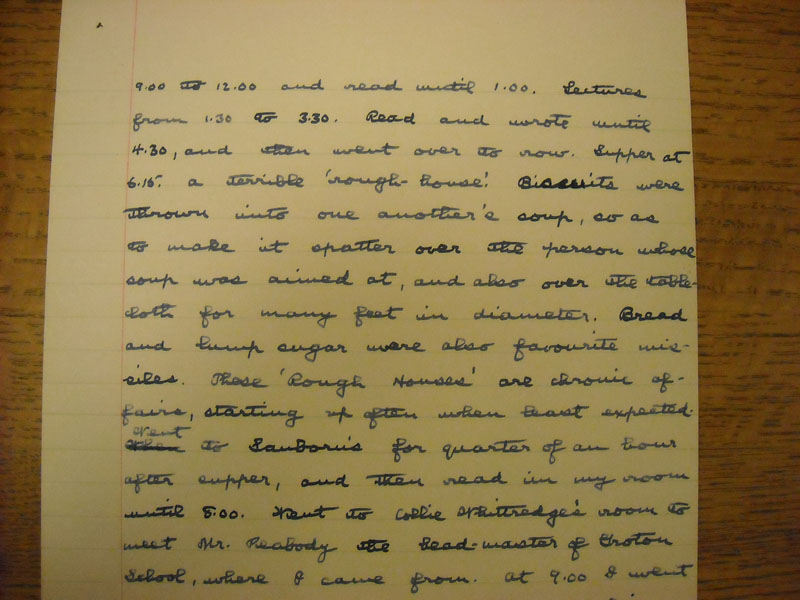

Over the next few weeks I’ll be showing you more of the incredible treasure trove of material that the Robinson family has been kind enough to share with us, but let’s just say we’ve taken a major step forward in locating specific items to purchase or replicate. For now, I wanted to share with you these six photos, of Chester (Chet) Robinson’s rooms. They show Robinson and his roommate Goodhue’s bay-windowed corner suite in the old Russel Hall, a Claverly like building that stood where today’s Russell (C-Entry) now stands. What’s fantastic about these photos, (and to my knowledge unique in the Harvard collection) is that they show the same room from three views, with two different decorative schemes. Somewhere during their four years, the pair decided to redecorate, in keeping with the shift in taste that was occurring right around the turn of the century. Ornate Victorian styling was moving out, and what would become Arts and Crafts, and eventually, neo-Colonial, was beginning to take hold. What’s critical about finding these pictures, just as we are about to paper the FDR suite, is what it reveals about the wallpaper: we’ve been wondering whether or not our selection of solid silk papers for the bedrooms, as we had seen in the Vanderbilt Suite, was typical of the time, or merely the product of Vanderbilt’s elevated design aesthetic. No longer:

Here’s the window seat before. Note the rather frilly drapes, and the striped wall paper. Two Morris chairs, similar to those coming to the FDR suite, and again, all those Harvard pillows we see in many of the photos. Heaven knows where we will find or recreate those! And how’s this for bizarre coincidence: the view out the windows reveals Westmorly, and the windows of the FDR suite!

Now look at this: a much more distinguished arrangement, with a solid, silk like material on the walls, almost identical to what we were guessing for the FDR Suite bedrooms. YES! The name placards, by the way, are another typical element of Harvard student rooms of the period, though generally they are located over the individual’s bedroom door.

A view of the hearth before. Note the Meerschaum pipes (present in almost every room photo) and the beer mugs (another ubiquitous student item.)

Here’s the hearth view after: you can tell it’s years later from the medals now hanging from the pictures: these are club and sports member medallions, and Dave’s family still has many of them, as well as the picture of dear old John the Orangeman, just visible on the mantle behind the mugs to right.

The doors to the bedrooms before: the curtains over the doorways appear in many of the room pictures of the period, and seem very odd to modern eyes. Most bookcases had curtains as well, as shown in the picture two above this one – to keep out coal and wood dust from the fires.

The door view after: a much more civilized arrangement than the ad hoc day bed previously. Note the Crimsons hanging from a hook on the wall. In general, it’s surprising how much the decor has matured over the interval. One (or both) of these gentlemen had a very good eye!

All in all, these six pictures provide a wealth of invaluable leads as to what kind of items we’ll need to acquire for the Suite, and as well as confirming both our reproduction of the printed study paper, and use of solid silks elsewhere. They also remind us what we often forget: the past is not static, locked at a single point and place the way we tend to view it from photos. It changed and moved, just like the present. Something to keep in mind when re-creaeting a set of rooms occupied for four years by two men of maturing times and taste…

We are all hugely grateful to Dave Robinson and his family for sharing this amazing time capsule with us, and I look forward to sharing more of it with you, our readers, over the next month.

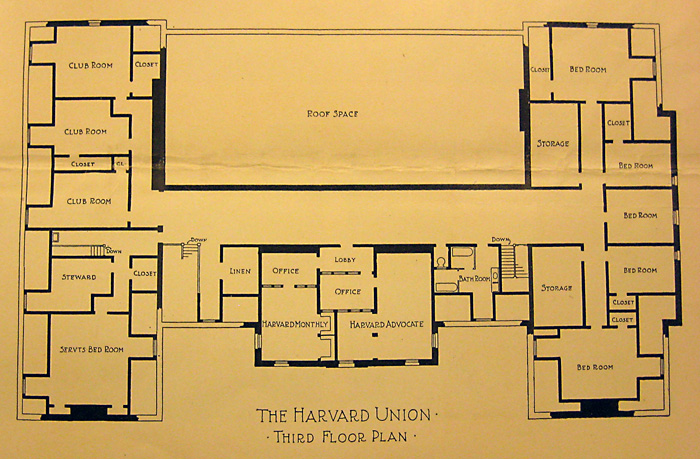

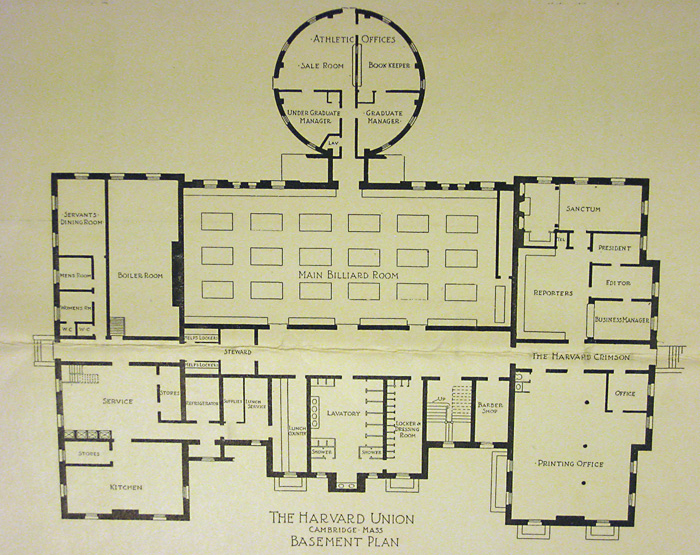

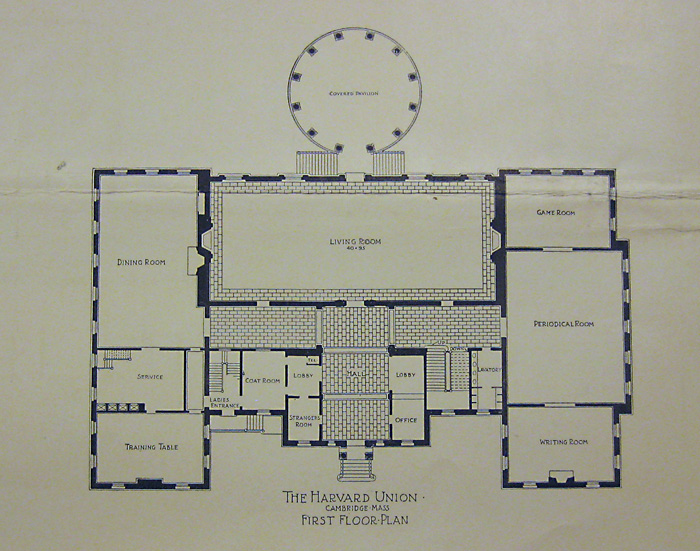

The top floor featured guest rooms for visitors (sans private bath, as was the custom of the day) plus the relatively modest homes of the Harvard Monthly and Harvard Advocate.

The top floor featured guest rooms for visitors (sans private bath, as was the custom of the day) plus the relatively modest homes of the Harvard Monthly and Harvard Advocate.